Reconsidering the Beauvais Workshop’s Première tenture chinoise

© Martin Eidelberg

Created April 2021

© Martin Eidelberg

Created April 2021

|

|

In the late seventeenth century the Beauvais tapestry workshop issued a marvelous series of nine tapestries: the Première tenture chinoise.1 One of the earliest and most significant examples of European chinoiserie, it proves to be a telling document of its age.2 Its rich mixture of Eastern and Western traditions is visually striking, and it offers insight into France’s appreciation and understanding of Chinese culture at this early date.

Although France displayed a strong interest in Chinese culture by the middle of the seventeenth century (one need only think of the Trianon de Porcelaine at Versailles), the term “chinoiserie” did not then exist as a word. Nor even in the eighteenth century. Instead, phrases such as “à la chinoise,” “façon de la Chine,” and “lachinage” were used. It was only in 1836 with the publication of an Honoré de Balzac novel that “chinoiserie” appeared in print, and afterwards it gained currency in the writings of Romantic authors such as Théodore de Banville and Edmond de Goncourt.3 Starting in 1873, “chinoiserie” finally gained official recognition in dictionaries such as that of Littré.4

More important than the history of the term’s etymology is the negative sense that became attached to it. For some in the nineteenth century, it implied the excesses of the Rococo; it was associated with frivolity and whimsy, an absence of reason. For those who understood Chinese culture and art, chinoiserie was often characterized as a Western misunderstanding of the East. This negativity is still frequently encountered today. Moreover, in these times of political correctness, it is not uncommon to find chinoiserie discussed in terms of racial caricature and imperialist suppression of “the other.” However modish such approaches may be, my aim is quite different. I wish to explore the positive aspects of early chinoiserie, and to focus on its serious aspects—its place within the Age of Enlightenment’s inquiry into the world at large.

The nine Beauvais tapestries are generally referred to as L’Histoire de l’empereur chinois (The History of the Emperor of China), a name that is not entirely satisfactory. It probably was intended to parallel the titles used to designate other famous tapestry cycles such as Peter Paul Rubens’ History of Constantine and Charles Lebrun’s History of Louis XIV. But whereas those cycles depict specific events in the history of famous monarchs, the scenes here do not portray specific historic events in any Chinese emperor’s life. Moreover, several in the series—the Astronomers, the Pineapple Harvest, the Empress of China Sailing—do not even include the emperor. Accordingly, it might be preferable to use the simpler title, the Tenture chinoise. This approximates the designation used c. 1700 in a memorandum by Philippe Behagle (1641-1705), the director of the Beauvais works; there he listed various sets of tapestries executed during his tenure: “Histoire de metamorphauce . . . tenture grotesque . . . Chinoise. . . .” Elsewhere, Behagle referred to the set as the “dessin de Chinoise.”5 Moreover, since these designs were replaced in the early 1740s by cartoons supplied by François Boucher, the first set is often referred to as the Première tenture chinoise in an attempt to clarify matters.

The authorship of the nine tapestries is largely resolved.6 One memorandum from Behagle misleadingly described the set as having been designed by “quatre illustre peintre [sic]” but it did not specify which four artists. A more reliable document of 1731, also from Behagle, specified that the set was designed by just three artists: Guy Louis de Vernansal (1648-1729), Jean-Baptiste Monnoyer (1636-1699), and Monnoyer’s son-in-law, Jean-Baptiste Belin de Fontenay (1653-1715).7 Vernansal was a history painter whose skill with large, multi-figured compositions establishes him as the principal designer of these tapestries. Exceptionally, the tapestry of The Collation in the Getty Museum actually bears the woven signature “Vernansal Invt. et Pint.”8 Flowers, fruits, and other still life elements were the specialty of Monnoyer and Belin. Since Monnoyer left for England in 1690, the project must have been launched before that date, at some time in the late 1680s. On the other hand, as will be shown, if elements in The Astronomers tapestry depend on images in Louis Daniel Le Comte’s Nouveaux mémoires sur l’état présent de la Chine (1697), the terminal date for the series must be set later than has been thought.9

The nine compositions have no fixed narrative order.10 Their measurements vary considerably, and designs were often abbreviated or enlarged depending on the specific demands of each commission. The original commission of these tapestries came from Louis Auguste de Bourbon, duc du Maine (1670-1736), the illegitimate but favored son of Louis XIV. Subsequently, a large number of sets of the Tenture chinoise were woven in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, but the duc du Maine’s set was especially deluxe, woven with gold thread. Significantly, the duke took special interest in China. He was reportedly moved in 1684 by the return from China of Jesuit Father Philippe Couplet and two Chinese converts to Catholicism. In 1685, Louis XIV sent a delegation of French Jesuits to China headed by Père Fontenay, with Guy de Tachard and other Jesuits. These men were skilled mathematicians and astronomers, and Louis XIV presented them with expensive instruments. The duke, then aged only fifteen, also contributed an astronomical instrument that he had commissioned for himself. The duc du Maine was also present at the reception of Siamese ambassadors at Versailles in 1686.11 At this time, there was a great controversy among the Jesuits and Western scholars as to whether Christians could condone and participate in many of the Chinese ceremonies—were they religious or civil in nature? Father Louis le Comte returned to France in 1691, and his letters describing his travels were published in the Mercure galante; His book, Nouveaux mémoires sur l’état présente de la Chine, appeared in 1697. Significantly, when Couplet’s book on Chinese rites and ceremonies appeared in print in 1700, it bore a dedication to the duc du Maine.12 In short, the Tenture chinoise was created during a time of especially rich interchange between West and East. The duc du Maine’s purchase of the first set of the Beauvais tapestries fits into this important context.13

The duc du Maine’s younger brother, Louis Alexander de Bourbon, comte de Toulouse (1678-1737), owned the fourth set woven of the Tenture chinoise. This is the set now in the Getty Museum. Not to be overlooked, Louis, duc de Bourbon (1668-1710), amassed an impressive collection of Chinese paintings and prints.14 An interest in the Far East was almost a hallmark of good taste among French nobility, and collections of paintings, porcelains, and objets were to be found in royal households everywhere.

A striking aspect of these Beauvais tapestries is their blend of East and West. Although supposedly set in China, the imagery is not always convincingly Eastern. The faces, especially those of the women, do not have Chinese features, and many of them have blond hair. The various pavilions are strikingly decorative and exotic, but they are not at all Chinese. Despite the authentic pagodas in some backgrounds, the pavilions in the foregrounds of The Emperor's Audience, The Astronomers, The Emperor of China Sailing, The Empress of China Sailing, and The Return from the Hunt are a strange hybrid, seemingly a cross between flamboyant Gothic and Mughal—far removed from Chinese architectural models.

Likewise, many of the accessory elements in these compositions are more Western than Eastern. For example, the carpets conspicuously displayed in the foreground of The Emperor's Audience and The Collation are Near Eastern in origin, not Chinese.

Indicative of the bustling trade between East and West, there is an abundance of Chinese blue and white porcelain as in The Empress at Tea and The Collation (fig. 2). But almost all these porcelains have ormolu mounts, a French modification that would not have been apparent at the Chinese court. We should also consider the way that this porcelain, as well as the silver and gold platters, is displayed at the left side of The Collation. Their manner of presentation is not at all Oriental in character. Rather, it reflects the way that such objets de luxe were arranged in pyramidal formations at French banquets, as is shown in Alexandre François Desporte’s full-scale portrayal of a regal buffet (fig. 3).

|

4. Beauvais Workshop, The Collation (detail), Los Angeles, Getty Museum. |

So too the silver coffee or chocolate pot on the table at the right in The Collation is not Chinese but French (fig. 4).15 Both the beverages and the vessel were newly introduced in France and were marks of distinction in aristocratic circles.

Despite such faux-Asian elements—and there are still many others that could be singled out—the Tenture chinoise frequently manifests an intent to be as authentically Chinese as possible, much more so than has been realized. As will be demonstrated, Vernansal and his colleagues relied on the many elaborately illustrated European books on China and the Orient. Although available in a variety of languages, almost all were translated into French.16 Much use was especially made of Johannes Nieuhof’s Ambassade de la Compagnie orientale des Provinces unies vers l’empereur de la Chine . . . (1665), and Arnoldus Montanus’ Ambassades memorables de la Compagnie des Indes orientales des Provinces unies vers les empereurs du Japon (1680). Even though the latter was about Japan, Japan and China were seemingly interchangeable regions. It is impossible to determine if all these books were consulted but there is incontrovertible proof that Vernansal and his colleagues appropriated imagery and consulted textual information from at least some of them.

|

|

5. Beauvais Workshop, The Emperor’s Audience (detail), New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

6. Title Page (detail), from Nieuhof, Ambassade de la Compagnie orientale, 1665. |

The Emperor’s Audience is a good example of the tapestries’ accuracy and specificity (figs. 1, 5). Conceived as a large horizontal composition, it assumes a commanding position within the series.17 With its formal symmetry, Vernansal’s depiction of the event may seem academic and Western, but this is misleading, especially when it is read against accounts of actual receptions such as the one described by Nieuhof, an account that Vernansal consulted. Nieuhof’s reception in Peking was paramount to the success of the Dutch ambassador’s trip because no trading would have been possible without the emperor’s approval.

There is a natural analogy between The Emperor’s Audience and the title page of Nieuhof’s book (figs. 5, 6): both show the enthroned emperor surrounded by guards, with supplicants and captives below. The symmetrical arrangement in both works is traditional, with the emperor at center; Nieuhof’s title page could well have inspired Vernansal when he began formulating his own composition. Whereas the physical restraints of the page size left little allowance for more of the surroundings, one might have expected that Vernansal, who had ample space, would have depicted a sumptuous throne room rather than an outdoor terrace. Yet, as Nieuhof described in his book, his reception took place in an open courtyard, with the emperor sitting on an elevated platform at the center.

Likewise, whereas the title page of Nieuhof’s book shows the emperor sitting on a traditional high-backed, four-legged chair, Vernansal devised seating that is both inventive and ambiguous. There actually is no chair. Rather, the emperor sits on the carpet, within the embrace of a golden, jewel-encrusted apse, corresponding somewhat to Nieuhof’s report that the imperial throne was gold and bejeweled. Whereas the engraver endowed the throne chair with lion’s-paw feet and dolphin-shaped arms, thus following a more traditional, European formula, Vernansal employed an apse with superficially Chinese features, especially the winged dragons for the bottom terminals.

Vernansal’s portrayal of the emperor sitting cross-legged on the carpet, while not conforming to our notion of how a royal personage should be presented, corresponds to many images of the Chinese emperor and lesser authorities in travel books. On the title page of Dapper’s treatise, surmounting all the allegorical figures, is the emperor of China, sitting on a carpet under a fringed canopy, his legs crossed beneath him (fig. 7). So too, in Nieuhof’s book one of the court officials is shown sitting cross-legged on a carpeted block (fig. 8). Similarly, in Montanus' publication a court official sits cross-legged, again on a carpet-covered dais (fig. 9).

It should also be noted that the images in Dapper and Nieuhof show the emperor wearing a headdress adorned with two peacock feathers, which was the distinctive ornament reserved for the emperor. Vernansal also rightly shows him wearing a sable fur headdress with two peacock feathers. This sartorial correctness is significant.

|

|

10. Beauvais Workshop, The Emperor’s Audience (detail), New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

11. Chinese Characters, from Nieuhof, Ambassade de la Compagnie orientale, 1665. |

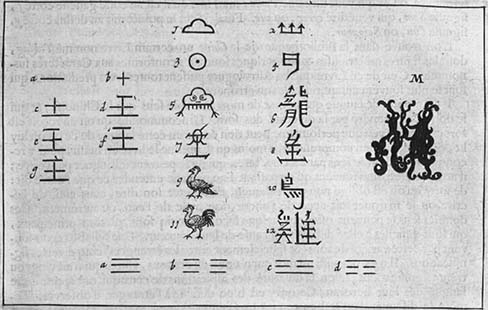

In Vernansal’s tapestry, the back of the imperial apse bears four lines of characters that, although organized in the Western manner of horizontal lines rather than vertical columns, resemble Chinese characters (fig. 10). In fact ,some of them look like ones in a table explaining Chinese characters in Nieuhof’s Ambassade de la Compagnie orientale (fig. 11). The character at the far left, the third line down, is somewhat like the character marked “5” on the Nieuhof chart, and the character next to it on the back of the throne looks like the Chinese character marked “1” on the chart. The symbol with upright prongs at the top resembles the character marked ”2” on Nieuhof’s chart. The other symbols on the throne back are of the same type, somewhat rudimentary rather than being the complex, multiple-stroke Chinese characters we might normally expect.

In the tapestry, next to the emperor, stands a single, fully armed warrior (not the dozen shown in the title page of Nieuhof’s book). At the other side of the emperor, a man tends an elephant whose body is half-hidden behind the throne. The inclusion of the pachyderm might seem incongruous, akin to an Orientalist fantasy, since we do not usually think of elephants in China, much less at the emperor’s court. Yet, in fact, Nieuhof describes three elephants present at the emperor’s reception—posed like sentinels at the gate to a lower courtyard (rather than on the dais).18 Vernansal’s reliance on Nieuhof’s text is important because it suggests that he was not dependent solely on the printed images. His reading of the actual text implies a deeper inquiry.

|

|

12. Beauvais Workshop, The Emperor’s Audience (detail), New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

13. Woman in a Rickshaw, from Montanus, Ambassades mémorables de la Compagnie des Indes orientales, 1680. |

We might also consider the woman in a wheeled chair at the far left side of the Emperor’s Audience (fig. 12). Of special note are the vehicle's heavily ornamented wheel spokes and hub. Unlike the thin, unornamented rickshaws normally used in China, Vernansal’s carriage recalls the one seen in Montanus’ Ambassades mémorables de la Compagnie des Indes orientales (fig. 13).

In short, many of the elements in The Emperor’s Audience register a concrete knowledge of Asian customs and objects. If the ensemble does not look Chinese to modern eyes, it may have convinced less sophisticated French viewers in the late seventeenth century.

|

14. Beauvais Workshop, The Astronomers, wool and silk, 318.8 x 424.2 cm. Los Angeles, Getty Museum. |

Concern with an accurate portrayal of China is also manifest in The Astronomers (fig. 14). Astronomy loomed large in Sino-French affairs because the Chinese were passionate about astronomy as well as mathematics, and the Jesuits believed that through these sciences they could more easily penetrate Chinese court circles. As was mentioned, many of the Jesuits who went to China were skilled in these disciplines.

Prominently featured in the foreground of The Astronomers are accurate depictions of celestial and terrestrial globes that were in the Peking observatory, and which had been made there under the instruction of Jesuit Father Ferdinand Verbiest (1623-1688); today they are in the National Museum in Beijing. The globes rested on splendid wooden stands carved in the form of dragons. Although these objects were in China, Vernansal could have learned about their appearance through engravings in Le Comte’s Nouveaux mémoires (figs. 15, 16).19 Yet if he was dependent on the images in Le Comte’s 1697 publication, that would imply a later terminal date for the design of the tapestries, at least for this one scene.20

|

|

17. Beauvais Workshop, The Astronomers (detail), Los Angeles, Getty Museum. |

18. Portrait of Father Schall, from Kircher, La Chine d’Athanas Kircher,1667. |

A prominent figure in The Astronomers is Jesuit Father Johann Adam Schall von Bell (1591-1666), head of the Imperial Astronomical Bureau and one of the first Jesuit astronomers who visited China (fig. 17). His aged face, trimmed beard, domed hat, and his rank badge with a design of a bird with outstretched wings are recognizable features. Father Schall is identifiable from the frontispiece of La Chine d’Athanas Kircher and, more germane, a full-page portrait of him appears in the text of that book (fig. 18). Schall figures prominently in the foreground of The Astronomers, shown calculating with calipers on one of the spheres, essentially the same action as in his engraved portraits.21 Here again, the tapestry’s inclusion of this portrait of the Jesuit is an important demonstration of the factual intent of the tapestries.

The Emperor of China Sailing and The Empress of China Sailing are two “travel” scenes with essentially the same elements and the same compositions (figs. 20, 21). Both show the same boat and comparable landing platforms positioned at an angle, and they have the same enframing architecture. Both monarchs sit proudly upright in the raised sterns of their vessels, immobile and looking fixedly forward.

|

21. A Noble Chinese Woman Arriving in a Boat, from Dapper, Tweede en derde Gesandschap, 1672. |

These maritime subjects are difficult to explain, especially because the Chinese court did not favor water travel. Nieuhof’s account, for example, makes no mention of the emperor or his court making a journey on water, but there are discussions in other travel books of Japanese and especially Siamese royal boat excursions. It is quite possible that Vernansal found inspiration in modest illustrations such as one in Dapper’s publication, where a joyous crowd enthusiastically greets a Chinese noblewoman standing in the prow of a small skiff (fig. 21).

|

22. Japanese Pleasure Boat, from Montanus, Ambassades mémorables de la Compagnie des Indes orientales, 1680. |

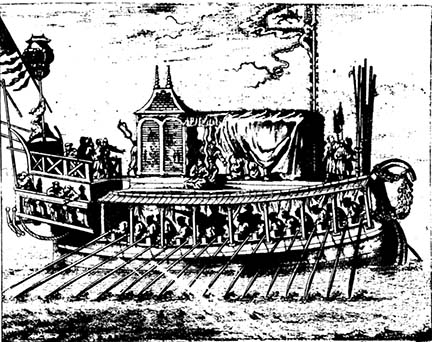

The boats in the two Beauvais tapestries are noteworthy. Although they have sails, they are powered by a crew of eight oarsmen who are positioned below at water level; the tops of their heads are barely visible in The Empress of China Sailing, and in the pendant Emperor of China Sailing they are confused with the people in the boat’s hull. Impressive imperial vessels like the ones in Vernansal’s scenes are discussed and illustrated in travel literature about the East, such as an illustration in Montanus’ Ambassades mémorables de la Compagnie des Indes orientales (fig. 22). These so-called pleasure boats were used to ferry the merchants and ambassadors arriving in Chinese ports and were remarked upon for their skilled teams of oarsmen, numbering twenty or more, which gave them great speed. Such boats seem not to have relied on a sail but Vernansal’s boat is so equipped, although not convincingly. With artistic license, Vernansal compressed the proportions of his ships with the result that the emperor and empress appear far too large, while the boats dwarf everything else. The effect is slightly surreal.

|

23. Chinese People Eating in a Boat, from Nieuhof, Ambassade de la Compagnie orientale, 1665. |

In The Empress of China Sailing, a table laden with food is set before her, and it fills almost all the space of the ship. There are comparable images in Nieuhof’s book and elsewhere of ordinary Chinese people in small, simple boats, eating from a board that fills the hold—but in an arrangement that is proportionate and more believable (fig. 23).22

|

|

24. Beauvais Workshop, The Empress of China Sailing (detail), Los Angeles, Getty Museum. |

25. Chinese Entertainers, from Nieuhof, Ambassade de la Compagnie orientale, 1665. |

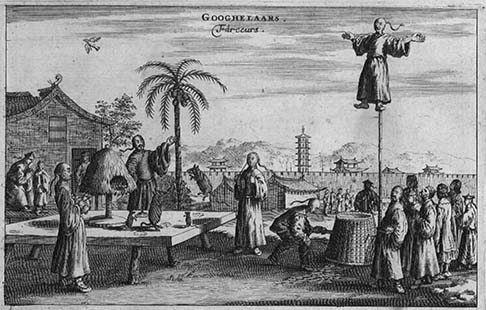

Lest there be any doubt that Vernansal referred to travel guides, this is clearly proven by the tableau of entertainers performing for the empress as she arrives in her boat (fig. 24). The whole of this scene is borrowed from an illustration in Nieuhof’s book (fig. 25).23 Everything in the tapestry—a musician playing a double flute; an acrobat standing atop a pole, balancing himself on one leg; even the trained rats dancing on the carpet—were taken from Nieuhof’s publication. Even if some of the figures were transposed for a more compact grouping, this overt borrowing is highly significant. It forcefully confirms that Vernansal was earnest in his search for accurate depictions of Chinese life and objects.

|

|

26. Beauvais Workshop, The Pineapple Harvest, wool and silk, 257.8 x 415.3 cm. Los Angeles, Getty Museum. |

27. Beauvais Workshop, The Pineapple Harvest (detail). |

|

|

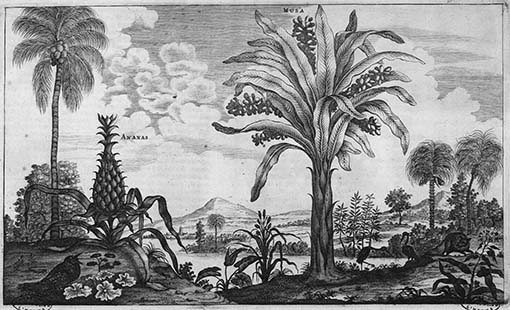

28. Pineapples, from Dapper, Tweede en derde Gesandschaft, 1672. |

29. Coconut palm, pineapple plant, and banana tree, from Montanus, Ambassades mémorables de la Compagnie des Indes orientales, 1680. |

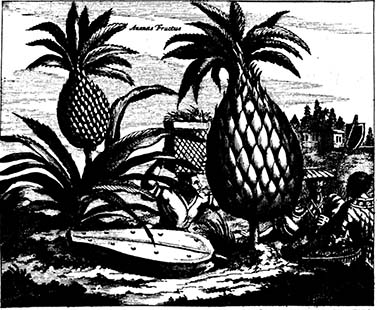

The fruits and vegetables of China were objects of curiosity to Europeans, and were invariably illustrated in the travel literature, occasionally with copies migrating from one book to the next. Among the most common fruits depicted were bananas, pineapples, mangoes, and the spiky, odorous durian; sometimes the fruits are shown close up but often the whole plant or tree is rendered. Often there were mistakes, especially in regard to the size of the pineapples, which sometimes dwarf the people harvesting them, as in an illustration in Dapper’s book (fig. 28).24 The image in Dapper’s book is unusual because most books on China generally do not show harvest scenes but, instead, emphasize the plants and their fruits as botanical studies. Vernansal’s design combines these traditions, showing the harvest but also emphasizing several other species of fruits. Nonetheless, pineapples are predominant in terms of what has been harvested. Several pineapples are growing in the foreground, one has been cut and is held in a peasant’s arms, and many pineapples have been loaded into the foreground baskets.

|

|

30. Beauvais Workshop, The Pineapple Harvest (detail), Los Angeles, Getty Museum. |

31. Coconut and palm trees, from Nieuhof, Ambassade de la Compagnie orientale, 1665. |

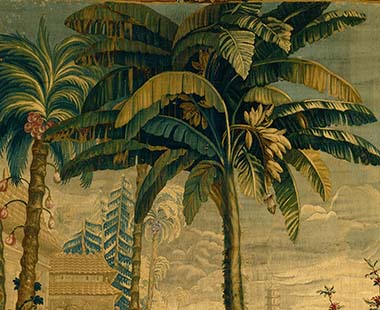

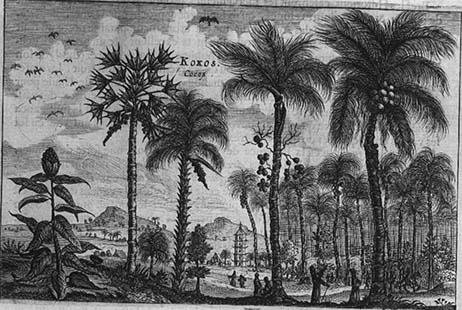

The upper reaches of The Pineapple Harvest are filled with a banana tree heavily laden with fruit and, at the left, a coconut palm (fig. 30). The fashion in which the feathery fronds of the very tall banana tree is drawn corresponds to the way they are engraved in travel books (fig. 31). So too the way that clusters of coconuts lie close to the tree trunk and individual coconuts hang pendulously from long stems attached to the trunk is telling, because just such coconut palms figure in the illustrations from Nieuhof’s and other travel books.

In the midst of the thick vegetation stands a well-dressed Chinese woman, clearly not a field worker, who holds a fan aloft to shield her face from the sun (fig. 32). This motif, I believe, was derived from an engraving in Montanus’ publication, where a noblewoman holds her fan overhead to protect her face from the sun’s rays (fig. 33).

Throughout this tapestry cycle are additional elements that are indebted to illustrations in the travel books under discussion. Not least, the costumes throughout the tapestries are rendered correctly. As opposed to the traditional, loose-fitting Chinese gowns, the men wear the new, courtly, Manchu-style robes, which are straight-seamed and tapering, with narrow sleeves (figs. 34, 35).

|

|

36. Beauvais Workshop, The Empress of China Sailing (detail), Los Angeles, Getty Museum. |

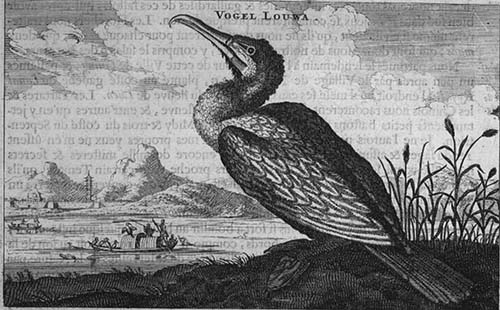

37. A Cormorant, from Nieuhof, Ambassade de la Compagnie orientale, 1665. |

Although abundant in this tapestry cycle, the birds—peacocks and miscellaneous fowl—are not particularly exceptional from an ornithological point of view. One that does invite attention is the aquatic bird in the foreground of The Empress of China Sailing (fig. 36). It seems probable that this bird is a cormorant, especially identifiable by its large, hooked beak, a distinctive pouch below, and the fish writhing within the beak. Most travel books on China illustrated the species (fig. 37). The authors were fascinated by the way that this bird, held captive by fishermen, dived for fish and then was forced to disgorge its catch.

|

|

38. Beauvais Workshop, The Empress of China Sailing (detail), Los Angeles, Getty Museum. |

39. Yangqin, 19th century, 70 x 25 cm. Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, gift of William Lindsey. |

The musical instruments displayed in several of the tapestries are, expectably, accurate in their depiction of these exotic Chinese objects. As has already been demonstrated in The Empress of China Sailing, the performer on a double flute was taken from Nieuhof (figs. 24, 25). In other instances, the instruments are depicted accurately but they cannot be traced to Western prints. The stringed instrument played by one of the women in the boat in The Empress of China Sailing (fig. 38) lies flat on the table, and is a small version of a Chinese yang-ch’in or yangqin (fig. 39), a type of Chinese dulcimer.25 While the woman in the tapestry plucks with her fingers, as though it were a harpsichord, it normally is sounded by hitting the strings with small mallets.

|

|

40. Beauvais Workshop, The Collation (detail), Los Angeles, Getty Museum. |

41. Photograph of Tsun-Yuen-Lui Playing a Chinese p’i-p’a. |

The entertainer at the left side of The Collation is playing not a Western lute but a Chinese p’i-p’a, as the instrument’s proportions and distinctive shape reveal (figs. 40, 41).26 However, some liberties have been taken. Normally, the instrument is held vertically and should be four-stringed, but in the tapestry it has additional strings and is held more horizontally like a lute or guitar. Furthermore, in the tapestry the instrument is being strummed by the fingers whereas the strings of the Chinese p’i-p’a are plucked by the fingernails.

How did Vernansal and his colleagues know about such Chinese instruments? Was it from textual discussions and illustrations in European travel literature, from Chinese books, or from actual instruments that had been brought back to the West? Even without an answer, it is again apparent that Vernansal portrayed Eastern artifacts as accurately as he could.

The Beauvais designers also displayed an awareness of Chinese architectural forms. In several of the tapestries, pagodas appear in the background landscape. They figure prominently in The Astronomers, The Emperor of China Sailing, The Empress of China Sailing, and The Pineapple Harvest (figs. 14, 19, 20, 26, 42). Depictions of such pagodas abound in travel books on China. For example, more than fifteen illustrations in Nieuhof’s publication are devoted to pagodas, either close up or as elements in the landscape. Although the eaves do not flare properly, a distant pagoda in The Empress of China Sailing closely resembles one pictured in Nieuhof’s book (fig. 42). In both, the bells are hung at every level, and the pinnacle on the roof is a two-part finial.

In certain wide examples of The Astronomers and The Emperor’s Journey, the leftmost portion of the tapestry depicts a landscape with a polygonal temple at the top of a summit of a broad staircase (figs. 44, 45). A building like this—with flaring eaves, peripteral columns, and a much reduced set of stairs—is illustrated in Nieuhof’s publication (fig. 46).

|

|

47. Beauvais Workshop, The Emperor Travels (detail), Los Angeles, Getty Museum. |

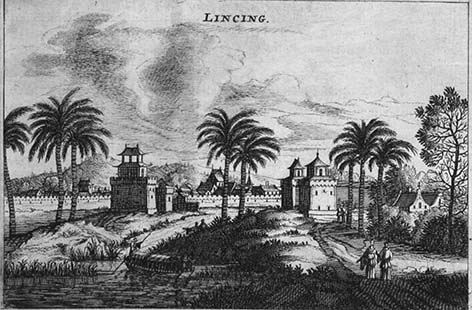

48. View of Lincing, from Nieuhof, Ambassade de la Compagnie orientale,1665. |

Seemingly inconsequential architectural motifs in these tapestries also affirm Beauvais’ reliance on travel books. For example, in compositions such as The Emperor Travels, the background includes a nondescript building whose uppermost level features a small, open-air structures with a peaked roof (fig. 47). Just such structures appear in the landscapes illustrated in Nieuhof and other books (fig. 48). Not a European architectural form, their appearance in these French tapestries again points to well-grounded research.

..........

Whether pineapple plants or pagodas, a troupe of entertainers or specific Chinese musical instruments, the Beauvais tapestries are remarkable for the amount of factual material that they boast. Putting aside the fantastic architecture that frames many of these compositions, and despite the presence of ormolu-mounted porcelains and blond-haired Chinese women, these tapestries reflect sincere and intelligent research into the appearance of the Chinese people and their culture.

The Tenture chinoise is a striking example of this early stage of chinoiserie. While we have examined these works in their own right, we should also consider this series within the context of other French chinoiserie from the period. Two important cycles come to mind. The first is the paintings executed around 1710 by Antoine Watteau at La Muette, a chateau on the outskirts of Paris. Although destroyed soon after it was executed, this cycle was engraved under the auspices of Jean de Julliene. From these engravings, my colleague Seth Gopin and I concluded that these paintings had been executed on black, faux-lacquer panels in imitation of Asian lacquer.27 And, like the Tenture chinoise, Watteau’s paintings presented an amazingly accurate knowledge of China and other Asian countries. The artist's source of information may have been a travelogue that included not only China but other countries such as Burma, Tibet, and Formosa. Interestingly, the patron of the La Muette project, Joseph Fleuriau d’Armenonville (1661-1728), also owned six tapestries from the Tenture chinoise.

A second major French cycle of chinoiserie is the beautiful set of designs that François Boucher created in the early 1740s to replace the worn-out cartoons from the Première Tenture chinoise. Echoes of Vernansal’s designs can occasionally be found in the second series and, more important, Boucher continued the tradition of consulting travel literature. One of his principal sources of inspiration was Montanus’ Ambassades mémorables de la Compagnie des Indes orientales, the publication that, as we have seen, was so valuable for Vernansal.28 It provided the artist with ideas for entire compositions and individual figures, although Boucher skillfully cloaked them in his suave rococo manner.

As all these works demonstrate, early French chinoiserie cannot be dismissed as mere rococo fantasy or ignorance. Even if there are unintentional errors and faux-pas, the underlying seriousness of these efforts needs to be recognized.

NOTES

1 I am grateful to Kee Il Choi Jr., moderator of Global Interchange: A Virtual Forum, for his support in this project. A slightly abridged form of my paper was presented to that group on March 19, 2021.

2 These tapestries have been studied by eminent scholars in the past, and this inquiry is much indebted to their work. See Jules Badin, La Manufacture de tapisseries de Beauvais depuis ses origines jusqu'à nos jours (Paris: 1909); Adolph S. Cavallo, Tapestries of Europe and of Colonial Peru in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Boston: 1967), 170-76; Edith A. Standen, “The Story of the Emperor of China: A Beauvais Tapestry Series,” Metropolitan Museum Journal, 11 (1976), 103-17; Charissa Bremer-David in Thomas P. Campbell, ed., Tapestry in the Baroque: Threads of Splendor (New York and New Haven: 2007), cat. 52.

3 Honoré de Balzac, L’Inderdiction (Paris: 1836), 163; Théodore de Banville, Les Cariatides (Paris: 1842), 17; Edmond de Goncourt, La Maison d’un artiste (Paris: 1881), 138.

4 Émile Littré, Dictionnaire de la langue française (Paris: Hachette, 1873), 1: 605.

5 Badin, La Manufacture de tapisseries de Beauvais, 11.

6 In his study of this cycle, Cavallo, Tapestries of Europe, mistakenly listed a tenth tapestry in the cycle: Gathering Tea. However, no such composition is known. Perhaps Cavallo was thinking of The Pineapple Harvest. Standen, “The Story of the Emperor of China,” 103, noted this error.

7 Badin, La Manufacture de tapisseries de Beauvais, 11: “les sieurs Batiste, Fontenay, et Vernansal.”

8 Carvalho, Tapestries of Europe, 170. Various examples of the Tenture chinoise have the name “Behagle” woven into the design, but this indicates only that Behagle was the artistic director of the tapestry works.

9 The dates generally assigned to the tapestries refer to their execution, not the creation of the cartoons. The Metropolitan Museum of Art dates its example of the Emperor’s Audience to the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century. The Getty Museum dates its seven tapestries to c. 1697-1705. The Philadelphia Museum of Art dates its Pineapple Harvest to c. 1686-90.

10 The Return from the Hunt, and The Empress Taking Tea under a Tent, however differ somewhat from the others; the figures are more slender than those in the rest of the cycle, and the accessory elements seem sparse and less inventive. Perhaps these designs were added slightly later or should be assigned to a different hand.

11 In October 1686, the Siamese ambassadors were brought to the Beauvais weaving shop.

12 The year 1700 also saw the publication of Confucius’ teachings in French.

13 Slightly later, the duchesse du Maine created a Cabinet de la Chine in her new Parisian hôtel. Its walls were lined with sections cut from a Japanese lacquer screen. See Nina Lewallen, “Architecture and Performance at the Hôtel du Maine in Eighteenth-Century Paris,” Studies in the Decorative Arts, 17 (Fall 2009-Winter 2010), 17-21.

14 See the inventory of his estate in Mireille Rambaud, Documents du minutier central concernant l’histoire de l’art , 2 vols. (Paris: 1964, 1971), 1: 532. The duke owned eighteen Chinese paintings on paper and forty-two others, including nineteen “painted prints” showing Chinese games.

15 See Beatrix Puente-Ballesteros, “Chocolate in China: Interweaving Cultural Histories of an Imperfectly Connected World,” in Chinese Medicine in the First Global Age (Brill: 2020), 58-107. The author would have us believe that the emperor’s raised goblet contains chocolate, which the emperor tasted but did not like.

16 Among the most prominent were Johannes Nieuhof’s L’ Ambassade de la Compagnie orientale des Provinces unies vers l‘empereur de la Chine, ou Grand can, 1665; Athanasius Kircher’s La Chine d’Athanas Kirchere, 1670; Olfert Dapper, Tweede en derde Gesansdchap, na het keyserryck van Taysing of China, 1672; Arnoldus Montanus’ Ambassades mémorables la Compagnie des Indes orientales des Provinces unies vers les empereurs du Japon, 1680; Olfert Dapper’s Asia, 1681; Louis Daniel Le Comte’s Nouveaux mémoires sur l’état présent de la Chine, 1697.

17 Scenes of royal receptions have a prominent role in French art. There are tapestries such as Charles Le Brun's Louis XIV Receiving the Papal Ambassador in The Life of Louis XIV. There are the many paintings showing Louis XVI Receiving the Siamese Ambassadors. Consider also the many paintings by Jean-Baptiste Vanmour of the Sultan receiving various European ambassadors; see Seth A. Gopin, Jean-Baptiste Vanmour, A Painter of Turqueries, Ph.D. thesis (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University, 1994), 96-98; also Seth Gopin and Eveline Sint Nicolaas, Jean Baptiste Vanmour, Peintre de la Sublime Porte, exh. cat. (Valenciennes: Musée des beaux-arts, 2009), 59-64.

18 Nieuhof, Ambassade de la Compagnie orientale (1665), 212: “nous nous promenions dans la basse-court, nous vîmes trois Elephants à la porte posés come trois sentinelles, qui etoient richement parés, & portoient des tours très-artistement faconnées.”

19 A bird’s-eye view of the observatory included in Le Comte’s Nouvelles mémoires reveals how the different sections of the site were screened into separate compartments. Something of this arrangement can be sensed in Vernansal’s composition.

20 Among others, Standen, “The Story of the Emperor of China,” 108, noted the resemblance between the astronomical globes depicted in the tapestries and those engraved in Le Comte’s 1697 publication, but did not consider the implications of the 1697 publication date vis-à-vis the design date.

21 In enlarged, wide versions of The Astronomers and The Emperor Travels, Schall reappears in the background, standing on a flight of steps leading to a temple (figs. 44, 45).

22 In the print, the people are shown eating with chopsticks. This was a skill that the French admired when the Siamese ambassadors visited Versailles and ate with these simple tools. Curiously, the use of chopsticks rarely figures in scenes painted by the French.

23 This dependence on Nieuhof was noted by Edith Standen, “The Story of the Emperor of China,” 110, 112.

24 Pineapples were not native to China. They were imported from Brazil via the Antilles in the sixteenth century.

25 See Stanley Sadie, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Washington, D.C., 1980) 4: 275.

26 Ibid., 4: 270-72. Standen, “The Story of the Emperor of China,” 109, described the instrument as “like an Indian sithar.”

27 See Martin Eidelberg and Seth Gopin, "Watteau's Chinoiseries at La Muette," Gazette des Beaux-Arts, s. 6, 130 (July/August 1997), 19-45. For contrary but not convincing views, see Katie Scott, “Playing Games with Otherness: Watteau’s Chinese Cabinet at the Château de la Muette,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 66 (2003), 189-248; also Yohan Rimaud, ed., Une des provinces du rococo, La Chine rêvée de François Boucher, exh. cat. (Besançon: Musée des beaux-arts, 2020), 52-59.

28 Perrin Stein has additionally discovered that in other chinoiserie designs Boucher borrowed from actual Chinese prints. See Perrin Stein, “Boucher’s Chinoiseries: Some New Sources,” Burlington Magazine, 138 (September 1996), 598-604; idem, “François Boucher, la gravure et l’entreprise de chinoiseries,” in Une des provinces du rococo, 223-37.