Defining the Oeuvre of Bonaventure de Bar (Part 3)

© Martin Eidelberg

Created June 20, 2013

Click to Print or Download PDF Version

The drawings of Bonaventure de Bar are highly problematic. One might have reasonably expected that despite the brevity of his career, he would have been an active draftsman. Like other masters of the fête galante such as Watteau, Pater, and Lancret, he would have drawn individual studies from models for the many figures in his paintings. Eighteenth-century sale catalogues offer some evidence that he did, but no examples are known today. These accounts also reveal that he made compositional studies and, indeed, the one extant drawing that has a credible claim to be by him is a finished work with three figures in a landscape. As will be seen, the artist’s drawings prove to be even scarcer than his paintings.

Only three eighteenth-century Parisian sale catalogues make reference to de Bar’s drawings. The first is the February 27, 1758, sale of the Coucicault and other collections. Here, a diverse group of drawings was lotted together: “Three sanguine drawings, including a landscape by Joseph Parossel [Parrocel], and a Country Party by Débarre.”1 One or more de Bar drawings figured in an anonymous sale held between December 13 and 22, 1762. Here again the lot was composed of drawings by diverse artists: “Twenty-two drawings by Chaperon, Lafosse, Debare, Boitard, Oudry, Huet and others.” 2 Lastly, at the Nourri sale, held between February 24 and March 14, 1785, a de Bar drawing was included in a group by miscellaneous French artists: “The Resurrection of Lazarus by Boullogne, Jesus Christ in the Manger by Champagne; & two others, one of which is by de Bar.”3 Although none of these references are sufficiently precise to allow us to ever identify the drawings should they appear, still, certain observations can be made. De Bar evidently used sanguine chalk and, more revealing, the first and third references suggest that he was accustomed to make compositional studies.

|

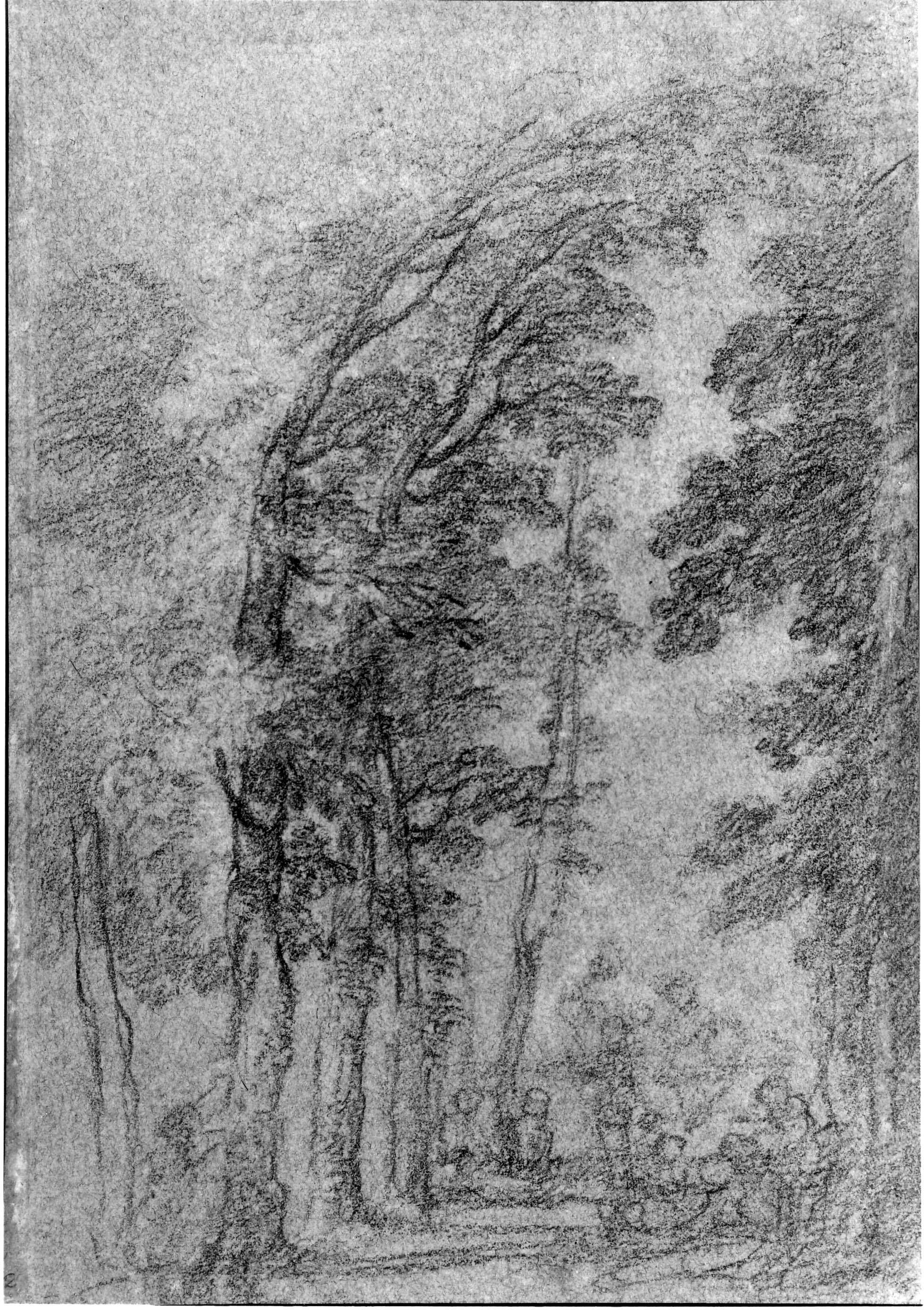

| 1. Bonaventure de Bar, Three Figures under Trees, 23.5 x 19.6 cm, red and white chalk on blue paper. Whereabouts unknown. |

Of the several extant drawings that have been associated with de Bar, perhaps only one has a valid claim. This is a study of three seated figures in a landscape (fig. 1). Drawn on blue paper in red chalk and heightened with white, it is a vibrant study, executed with verve.

|

2. Bonaventure de Bar, A Village Fair (detail), c. 1728. Paris, Musée du Louvre. |

Most important, these three figures correspond to the work in the left foreground of de Bar’s 1728 morceau de réception, now in the Louvre (fig. 2). Although it has not been mentioned by those writing on de Bar, the drawing has been in the public sphere for more than a half century. It appeared in a 1958 auction in Paris, with the attribution to de Bar already in place and its relation to the Louvre painting fully acknowledged.4 It reappeared at auction in 2007 under similar circumstances.5 Looking back at the three eighteenth-century references we have brought together, two (one explicitly, one implicitly) show de Bar making compositional studies. The distinctive, painterly draftsmanship of this extant study suggests what we might perhaps expect from other drawings by this master.

|

|

3. Bonaventure de Bar, The Village Wedding (detail). Whereabouts unknown. |

4. Bonaventure de Bar, A Country Fête (detail). Houston, Museum of Fine Arts, Sarah Campbell Blaffer Foundation. |

A potential candidate to include in de Bar’s oeuvre is a small study (11.5 x 9.7 cm) reputedly showing the woman sitting on the ground, seen from behind, that is depicted in the preceding drawing. And, like that drawing, this too was rendered in red and white chalk on blue paper. Moreover, it was sold in the same 1958 Paris auction.6 It was presumably a detailed study from a model. As such, de Bar used it not only for the Louvre picture but also for the ex-Arenberg Village Wedding (fig. 3) and the small fête galante in the Blaffer collection (fig. 4). The use of a single study for several paintings was, of course, common for Watteau and his followers. It is fascinating that this missing drawing and the compositional study were still paired after World War II, more than two centuries after the artist’s death. One can only speculate how they came together. Had they been like that since the eighteenth century? After all, it would be quite difficult for a modern collector, howsoever clever, to purchase them separately since de Bar drawings are not readily available on the market.

Karl T. Parker mentioned a sanguine double figure study in the Musée des Beaux-Arts of Orléans that was “inscribed by a fairly old hand with the artist’s name.”7 According to the museum’s records, the drawing showed two resting vagrants (“chemineaux”) and measured 55 x 23 cm. Unfortunately the drawing was destroyed in a bombing raid in June 1940 without ever having been photographed. The lack of an image coupled with Parker’s caveat that “it has yet to be proved that this attribution is ... trustworthy” leaves us on uncertain grounds.

|

5. Anonymous, Village Fête, 17.7 x 22.9 cm, black chalk. Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des arts graphiques. |

The most often cited candidate for de Bar’s oeuvre is a compositional study in the Louvre’s Département des arts graphiques (fig. 5).8 It shows a large gathering of people outside an inn, with other buildings in the distance, and peasants in the foreground performing a rustic dance. The drawing has a good provenance: in the eighteenth century it belonged to the marquis de Calvière and then passed to the collection of Pierre Marie Gaspard Grimod, comte d’Orsay. It was seized in the Revolution. At the bottom left, below the drawing, is the compelling inscription “De Bar. F.~1730.~”. This text helps to explain why the drawing has so often been cited by scholars writing on the artist.9 Yet an attribution to de Bar is highly unlikely. The linear draftsmanship is unrelated to the painterly rendering of the three figures sold in 2007 (fig. 1). Also the type of overtly Flemish village kermesse seen here is unrelated to the subject matter of de Bar’s known paintings. The so-called signature at the lower left has no credibility for several reasons. First, it is not the artist’s personal signature but, rather, a name or label written in a neat, secretarial hand. Also, it is rendered in bistre ink, unlike to the black chalk of the drawing. Most distressing, the designation of “1730,” an integral part of the inscription, is a year after de Bar died. In short, this so-called signature is merely a dealer’s or collector’s later, unreliable information. This was recognized by Guiffrey and Marcel when they catalogued the drawing in 1907. They cautiously classified it as “attributed to de Bar” yet they maintained that the drawing was by him because it supposedly had the same characteristics as his paintings, a thesis that is difficult to support.

Another drawing that has been listed under de Bar’s name is a study of a seated woman holding a musical score on her knees. The verso shows a study of a hand on the verso. This sheet was sold from the Rudolphe de Baillencourt collection in 1893 with an attribution to de Bar, which is in itself noteworthy since normally French drawings without a known artist were ascribed to Watteau or satellites such as Pater and Lancret, rather than this lesser known artist.10 Its measurements were recorded (27 by 16 cm) but, unfortunately, no image of it is known. Although the Baillencourt drawing has occasionally been cited in the literature, without better documentation no judgment can be rendered as to the justness of the attribution.

6. Pierre d’Angellis, Study of a Standing Man with a Bowl, 29 x 18 cm, black chalk. Rennes, Musée des Beaux-Arts. |

7. Pierre d’Angellis, Study of a Hurdy Gurdy Player, 27.5 x 18 cm, black chalk. Rennes, Musée de Beaux-Arts. |

8. Pierre d’Angellis, Study of a Man with a Staff, 16 x 9 cm, black chalk. Rennes, Musée de Beaux-Arts. |

Only a handful of other drawings have been given to de Bar, surprisingly few in light of how many paintings have been falsely ascribed to the artist. Among the most prominent are a group of figural studies in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Rennes (figs. 6-8). They came from the collection of a local Maecenas, Christofle Paul, marquis de Robien (1698-1756). Valabrègue enumerated five of them only casually: a man with a staff, a woman seen from behind, a woman seen frontally, four black chalk studies, and a study of a man.11 Since there actually are some forty drawings in this group in the Rennes museum, many of them fitting these descriptions, Valabrègue’s listing is too imprecise to be useful. Hans Vollmer’s subsequent listing of de Bar’s oeuvre was still vaguer, citing “some drawings” in the Rennes museum.12 Huard listed only the drawing of the standing man with a staff.13 Finally, Robert Rey reasserted Valabrègue’s attribution of the five Rennes drawings to de Bar, illustrating what was supposedly the man with a hurdy-gurdy but is, in fact, a study of a man holding a bowl (fig. 6). Ultimately it little matters how many or which particular sheets these critics accepted for none of these Rennes drawings are by de Bar. Instead, they are by another of Watteau’s satellites, Pierre d’Angellis. This was pointed out by Karl T. Parker, who based his argument on the fact that Angellis spent the last years of his career in Rennes.14 Indeed, these drawings, which span the entire range of his career, were probably in the artist’s studio when he died and then must have been sold or given to Robien.15 Moreover, there are one-to-one correspondences between many of these studies and the figures in his paintings.

Parker’s reassignment of the drawings to Angelis was apparently done on the basis of Rey’s book, without his having been to Rennes and without considering the relation of those drawings to Angellis’ paintings. This situation was remedied with Pierre Lavallée’s publication on the Rennes collection some six years later, where he listed thirty-one of the sheets under Angellis’s name. In the last half century the Rennes drawings have rightly disappeared from the literature on de Bar.

Surprisingly, Guillaume Glorieux recently reclaimed one of the Rennes sheets for de Bar, namely the study of the hurdy-gurdy player (fig. 7).16 It is not apparent why he singled out this particular sheet, especially since its technique of insistent diagonal hachures and the stolid, almost Flemish features of the model are in complete accord with the many other Angellis drawings at Rennes. Even the smallest details, such as the way that the subsidiary studies of the hands are sharply demarcated at the wrist, as though they were detached parts of a mannequin, is typical of Angellis’ approach. In short, there is no reason to attribute the drawing of the hurdy gurdy player to de Bar rather than to Angellis.

Other figure drawings that have been associated with de Bar can be quickly dispensed with. A study of two figures—a seated woman and a standing man—executed in sanguine and heightened with white, on blue paper, was sold in Paris in 1928 with an attribution to de Bar.17 But as there is no image, here again no judgment can be rendered.

9. Anonymous, A Dance, 22.9 x 31.4 cm, black, red, and white chalk. Formerly Amsterdam, Sotheby’s. |

A compositional study that was formerly in the collection of the celebrated Dutch scholar Dr. I.Q. van Regteren Altena had previously been ascribed to de Bar and was then reclassified as a follower of Watteau (fig. 9).18 Yet neither attribution is convincing. The rather loose draftsmanship, the meaningless use of red or black chalk for different figures, and the clumsy decorative curves as a border suggest that this is a fanciful recreation of the rococo concocted in the nineteenth or early twentieth century.

Lastly, mention should be made of two sheets in the Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco. Although they are not a pair and have separate histories, the course of their attributions is remarkably parallel. One drawing shows a standing man, slightly bent to the left, executed in black, red, and white chalks on blue paper (fig. 10).

|

|

12. Michel Barthélemy Ollivier, Seated Male Figure, 19.2 x 13.2 cm, red and black chalk on blue paper. San Francisco Museums of Fine Arts, George de Batz collection. |

13. Michel Barthélemy Ollivier, Fête Champêtre under Trees, 19.2 x 13.2 cm, black chalk on blue paper. San Francisco Museums of Fine Arts, George de Batz collection. |

The recto of the second sheet shows a seated man, drawn in red and black chalk, while the verso, rendered in just black chalk, is of sketchily indicated people under an allée of trees (figs. 12-13). Earlier in the century the two sheets were attributed to Watteau, after World War II they bore an attribution to de Bar, and then were reassigned to Michel Barthelemy Ollivier (1712-1784).19 It has been suggested that the standing man is a study for a valet in Ollivier’s Fête Given by the Prince de Conti at the Île-Adam, a painting shown in the 1777 Salon and now at Versailles (fig. 11). While the correspondence is less than exact, nonetheless, the attribution to Ollivier seems plausible. The sequence of changed ascriptions reflects a trajectory often found in twentieth-century connoisseurship: a baseless optimism that ascribed almost everything to Watteau, followed by a seemingly random assigning of works to minor masters, and now a more reasoned approach.

What ultimately can be concluded about de Bar’s draftsmanship? Curiously little. In addition to the three eighteenth-century sale references, we have one extant drawing and knowledge of several other possible candidates. This is a statistically small number of examples, far too few even for an artist whose career lasted only a decade. Undoubtedly additions to his oeuvre will be found in the near future, discoveries made perhaps among the many drawings misattributed to Pater, Lancret, and other Watteau satellites. Time will tell if this is true.

NOTES

1. Sale, Paris, February 27, 1758, Coucicault collection and others, lot 15: “Trois Desseins à la sanguine, dont un Païsage par Joseph Parossel, & une Recréation champêtre par Débarre.” They were bought by Jean François Marie Bellier for 4 livres.

2. Sale, Paris, December 13-22, 1762, lot 36: “Vingt-deux Desseins de Chaperon, Lafosse, Debare, Boitard, Oudry, Huet & autres.” The lot sold for 8 livres 3 to the dealer Peeters..

3. Sale, Paris, February 24-March 14, 1785 [this lot was offered on March 7], Nourri collection, lot 165: “La Résurrection du Lazare, de Boullogne; Jesus-Christ à la crèche, par Champagne; & deux autres, dont une par de Bar.” This group sold for 25 livres.

4. Sale, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, June 18, 1958, lot 31.

5. Sale, Paris, Christie’s, March 24, 2007, lot 68

6. Sale, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, June 18, 1958, lot 32.

7. Karl T. Parker, “Mercier, Angélis and de Bar,” Old Master Drawings, 7 (December 1932), 40.

8. Inv. no. 23688. Jean Guiffrey, Pierre Marcel et al., Inventaire général illustré des dessins du Musée du Louvre et du Musée de Versailles. École française, 12 vols. (Paris: 1907-75), 1: 44-45, cat. no. 195.

9. It was accepted as being by de Bar by Antony Valabrègue, “Bonaventure de Bar (1700-1729),” La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité (December 30, 1905), 344. It has continued to be listed by scholars unto the present: see Hans Vollmer, “Bar,” in Ulrich Thieme, Felix Becker, and Hans Vollmer, eds., Allgemeines Lexikon der bildende Künstler, 37 vols. (Leipzig: 1907-50), 2: 450; Georges Huard, “Debar,” in Louis Dimier, ed., Les Peintres français du XVIIIe siècle, 2 vols. (Paris and Brussels: 1928-29), 1: 299; Robert Rey, Quelques satellites de Watteau (Paris: 1931), 145 and plate XXIV; Guillaume Glorieux, “Un Ensemble de décors peints par Bonaventure de Bar,” Revue de l’art, no. 150 (2005), 51.

10. Sale, Saint-Omer (Pas-de-Calais), December 18-21, 1893, Rudolphe de Bailliencourt, dit Courcol, collection, lot 6: “Jeune femme assise tenant un cahier sur ses genoux, au revers, etude de main.” It was cited by Hippolyte Mireur, Dictionnaire des ventes d’art faites en France…, 7 vols. (Paris: 1911-12), 1: 106; also Emmanuel Bénezit, ed., Dictionnaire critique et documentaire des peintres, sculpteurs…, vols. (Paris: 1911), 1: 349; Valabrègue, “Bonaventure de Bar,” 345; Rey, Quelques satellites de Watteau, 149.

11. Valabrègue, “Bonaventure de Bar,” 345.

12. Vollmer, “Bar,” 450: “im Museum zu Rennes einige Bleistiftzeichnungen mit Figurenstudien von ihm aufbewahrt.”

13. Huard, “Debar,” 299.

14. Parker, “Mercier, Angélis and De Bar,” 36-40.

15. Rey claimed that Robien bought these drawings at Pierre Crozat’s sale in 1741. However, Crozat was not particularly interested in drawings by contemporary French artists and no de Bar or Angellis drawings are listed in the catalogue of his sale..

16. Glorieux, “Un Ensemble de décors peints par Bonaventure de Bar,” 51.

17. Paris, Hôtel Drouot (salle 1), April 27, 1928, lot 2. The drawing was measured as 19 x 21 cm.

18. Sale, Amsterdam, Sotheby’s, May 19, 2004, I. Q. van Regteren Altena collection, lot 154.

19. See Phyllis Hattis, Four Centuries of French Drawings in The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (San Francisco: 1977),125-26, cat. nos. 88-89; also Pierre Rosenberg and Louis-Antoine Prat, Antoine Watteau, 1684-1721, Catalogue raisonné des dessins, 3 vols. (Milan: 1996), 3:1254-55, cat. no. R401.