RECONSIDERING WATTEAU’S ENSEIGNE DE GERSAINT

© Martin Eidelberg

Created September 2020; revised November 2020

© Martin Eidelberg

Created September 2020; revised November 2020

|

|

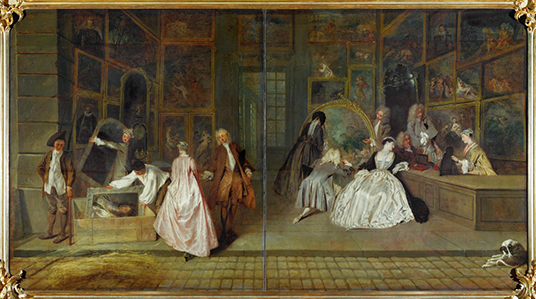

Three hundred years ago, in late 1720, Watteau painted one of his chefs d’oeuvre, the great signboard that he made for his friend, the art dealer Edme Gersaint (fig. 1).1 It is a singular work, even more so because the circumstances of its creation were recorded by Gersaint himself:

On his [Watteau’s] return to Paris, which was in 1721 [sic], during the first years of my establishment, he came to me to ask if I would agree to receive him, and allow him to stretch his fingers, those were his words, if I were willing, as I was saying, to allow him to paint a plafond that I was to exhibit outdoors. I had some reluctance to grant his wish, much preferring to occupy him with something more substantial; but seeing that would please him, I agreed.2

The picture hung outside Gersaint’s shop at 35 Pont Notre-Dame, over the entrance doorway. Its enormous scale and original shape corresponded to the demands of the architectural setting—a lunette space under a depressed arch (fig. 2). All the shops on the bridge had uniform facades, but once Watteau’s signboard was in place, Gersaint’s store would have stood out. The painting met with great approval and admiration. As Gersaint wrote, “One knows the success this work had . . . it attracted the looks of passersby; and even the most skilled painters came several times to admire it.”3

The signboard’s success was so great that Gersaint promptly took it down and installed it in his gallery as a work of art. At that time the picture was radically modified. The originally rectangular canvas had been folded back to create the lunette shape, and now was unfolded to reestablish a rectangular field (fig. 3). Also, a strip of canvas was added across the top. These additional portions were painted with framed pictures to match those depicted on the gallery walls below. It is generally thought that these modifications were executed by Watteau’s assistant, Jean-Baptiste Pater.

|

4. Jean-Baptiste Pater after Watteau, L’Enseigne de Gersaint, oil on canvas, 50 x 82 cm. Geneva, private collection. |

Pater was also called upon to paint a copy of the signboard, much reduced in scale (fig. 4). It measures only one-third the size of the original.

|

|

When time came to engrave the painting for Jean de Jullienne’s Oeuvre gravé, Pierre Aveline turned to Pater’s version and copied it in reverse (fig. 5). Some have argued that Pater’s copy was specifically made for Aveline’s use, but it is also possible that it had been commissioned by an admiring amateur who knew he would be unable to acquire the original.4

Watteau’s signboard, so strikingly beautiful, is a seemingly effortless portrayal of contemporary life among wealthy members of Parisian society. The clients in the picture consider works of art to adorn their homes and assert their status. The woman seated at the counter contemplates luxury goods, lacquered objets de toilette, and at the left a mirror and elaborate table clock emphasize the richness of Gersaint’s commerce. Unlike Watteau’s fêtes galantes, which often appear idyllic, L’Enseigne conveys a sense of the urban reality enjoyed by the leisured class. As fresh and spontaneous as Watteau’s painting may seem, several Watteau drawings of posed models remind us that the artist composed the work with the same careful artifice that he employed for his fêtes galantes. Moreover, and this is the main thrust of this enquiry, L’Enseigne is bound to pictorial conventions that Watteau undoubtedly knew.

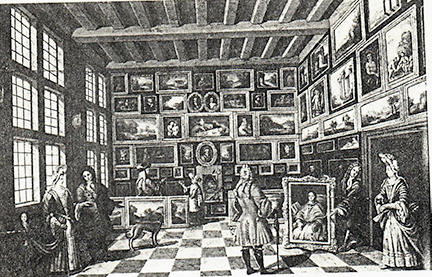

When Watteau began work on his signboard for Gersaint, he would have been well aware of the tradition of depicting commercial art galleries and private art collections; it was a well-established theme in European painting, especially in Flemish and Dutch art. One naturally thinks of early seventeenth-century scenes by David Teniers and other masters, where the riches of these collections are portrayed with precision. Such pictorial inventories still function that way for modern viewers hoping to reconstruct collections that have long since been dispersed.

|

8. Anonymous Dutch artist, At a Painting Dealer’s Shop, c. 1690-1715, oil on panel, 40.5 x 62 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

Moreover, these scenes were not confined to the early seventeenth century.5 They were still a part of European pictorial language in Watteau’s time, as can be seen in a painting that, as evidenced by the clothes depicted, dates from c. 1690-1715, in other words, shortly prior to L’Enseigne (fig. 8).6 Watteau was cognizant of this tradition, for while he gave primacy to the figures and left the background pictures in shadow, still, a surprising number of Gersaint’s paintings are identifiable.

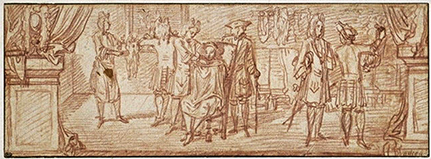

Most important, when Watteau offered to paint a signboard for Gersaint, he already had the experience of having painted other signboards. This skill was among his professional credentials, and undoubtedly was one of the reasons he made his offer. He had valuable experience that he could call upon. Of particular relevance are two red chalk drawings in the Louvre that record his early ventures in this genre. They have been discussed in the past in relation to Gersaint’s signboard, but their implications deserve further attention. Although both portray shop interiors, they are quite different from each other.

|

|

The first design is a scene of a barber shop (fig. 9).7 At the center a man is being shaved, while at the right another is shown a periwig. At the left a servant brushes out a periwig, while a gentleman ponders his appearance in a mirror on the back wall. How is this drawing to be understood? It is not simply a genre scene studied from life. Atypically, Watteau has constructed the scene as a rigidly symmetrical composition. The man being shaved is placed directly at the center, and the subsidiary activities are set at the sides, the one balancing the other. Equally important, the symmetry is enhanced by pedestals and drapery that terminate both sides. In fact, this symmetry would have been more apparent had the drawing not been cut at the right side, thus leaving only a portion of what probably was a larger expanse of pedestal and drapery. The formal nature of Watteau’s composition calls attention to itself. Recalling his arabesque designs, and unusual paintings such as L’Alliance de la musique et de la comédie, which functioned like a sign, this composition should be understood as a preliminary design for the sign of a barber shop; an idea reiterated by almost all Watteau scholars.8 Looking back from the perspective of L’Enseigne, certain elements in the Louvre drawing adumbrate features of the Berlin painting. The bottom edge of the drawing is not just a framing element—that would have been rendered as horizontal lines; rather, its diagonal strokes indicate a curb that must be surmounted to pass from the street into the shop, and this curb is just what Watteau included in L’Enseigne.9

|

|

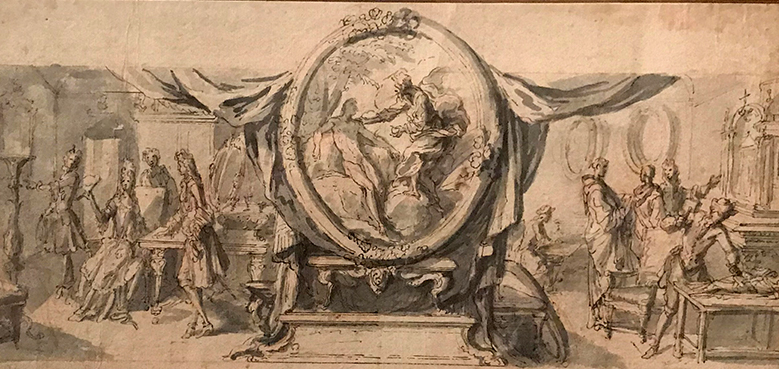

When Watteau created his design for a barber shop (fig. 9), he did not start from scratch. Rather, he worked within the prevailing conventions for signboards. Although he may have been stimulated by specific prototypes, we can only point to the few examples that have survived. Of particular relevance is a design for a signboard (or trade card?) executed by Antoine Dieu at the end of the seventeenth or beginning of the eighteenth century (fig. 10).10 Like Watteau’s design, here too there is a central focus: a medallion with God or Zeus, the primal sculptors, creating man from clay. Flanking this medallion are scenes of a lady of quality meeting with the artist, and workmen involved in the fabrication of sculpture. As in Watteau’s drawing where drapery terminates both sides, here drapery is furled around the central medallion and flares out at the top and bottom to further the symmetry. The parallels between the structure of this design and Watteau’s suggests that our artist was guided by convention more often than we have realized.

|

|

|

12. Anonymous French artist, Marchande de linge, engraving c. 1685-1700. |

The second Watteau drawing in the Louvre shows the interior of a draper’s shop (fig. 11).11 It recalls the type of imagery seen in popular prints, such as an anonymous engraving of a woman selling linens (fig. 12). These prints were an important source for the genre subjects adopted up by Watteau and his generation. Adhémar began to explore this rich terrain in the years before World War II, and the examples since brought to light suggest that Watteau would have enjoyed these prints. The engraving of La Marchande de linge offeres provocative parallels with the Louvre drawing and ultimately, both are close to L’Enseigne de Gersaint.

At the right of the Louvre drawing of a drapers shop, a gentleman steps up from the street into the shop, to converse with a shop worker holding a bolt of cloth. Beyond them, a young man leans casually against the counter and speaks with a saleswoman. Still farther back, a servant boy waits attentively. Here too, elements look forward to the Enseigne. Key features in this design are the shop masonry wall at the right and the movement of the man at the side who steps from the street into the shop interior. In L’Enseigne the same effect is achieved: the cobblestone roadway and the masonry wall at the left demarcate the exterior and interior spaces. The man standing against the wall at the left, and the dog lying in the street at the right emphasize these spatial distinctions. The play between interior and exterior spaces, and the inclusion of a portion of the masonry wall are elements found in other signs of this period, such as one for a hatter’s shop published by Jacques Wilhelm (fig. 14).12

Were there a second and opposite scene at the left to complete the Louvre composition, it would be even more like L’Enseigne. Watteau’s sketch originally extended more to the left, as is shown by the chalk lines not stopping before the border but continuing on. If the composition did extend farther to the left, or if a second sketch were drawn on another sheet, which I believe is a strong possibility, then the resemblance to L’Enseigne would be striking indeed.

Watteau had a rich treasury of older signboard designs to inspire him. There undoubtedly was a still larger repertoire that he could have drawn upon, one which has been diminished by time.

|

|

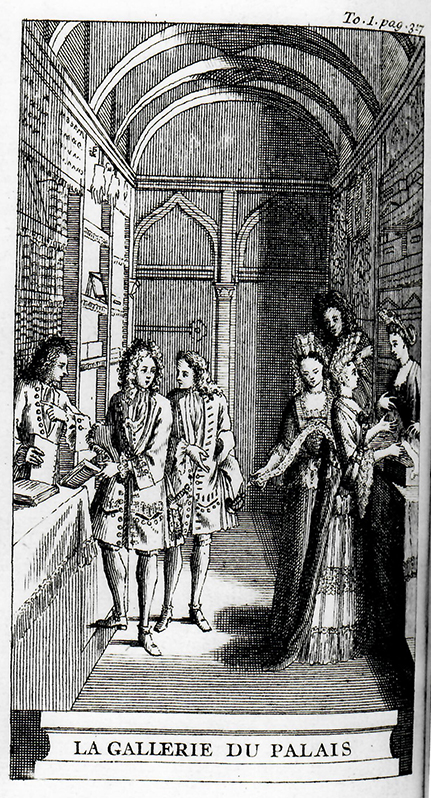

Also relevant to L'Enseigne is a commission to the young Watteau that we have only recently published—a series of frontispieces for 1714 publications of the plays of Thomas and Pierre Corneille.13 The frontispiece for one of Thomas’ pieces, La Gallerie du palais, shows the interior of a draper’s shop, with the male customers on one side and the female customers on the other (fig. 13). This compositional scheme, as well as the general lines of the architecture, were already present in the Dutch model that Watteau worked from. While one should not claim that La Gallerie du palais led directly to the design of L’Enseigne, it does show that such images of shop interiors were part of his repertoire before he embarked on Gersaint’s signboard. The separation of the clients into two groups, the receding side walls, the central doorway—all these elements reappear in L’Enseigne.

We should also consider works by other artists, especially Parisian ones, that Watteau may have been aware of. Unfortunately, little of early eighteenth-century Parisian genre painting has come down to us, and signboards are particularly susceptible to the ravages of time and use. Although few in number, some have survived. Not only do they offer analogues with the Watteau drawings we have discussed but, moreover, they are particularly relevant to L’Enseigne. A pair of pendant paintings showing a draper’s shop, which François Boucher published in the 1950s and by me a decade later, have not engaged modern scholars, although they are of prime importance (fig. 14).14 Their recent auction offers an opportunity to reconsider the question.15

When Boucher published the two pictures, he presented them as anonymous French works from c. 1700. The question of attribution still stands today. In certain ways the figures recall the animated staffage in paintings such as Pierre Denis Martin’s View of the Quai de la Rapée in the Musée Carnavalet, painted around 1700. Certainly these anonymous paintings are from the same period. The dramatically high lace fontanges worn by the two women establish that the paintings were executed in the last decade of the seventeenth century or the first decade of the eighteenth, that is to say, before Watteau’s two drawings for signboards. Their settings anticipate the solution our artist used for his Enseigne, namely a view from the street into a gallery, with masonry walls at one side suggesting the exterior of the building. At the right our attention focuses on a vendeuse behind her counter, showing wares to clients, while the left-hand canvas includes the packing of cases—a striking parallel to Watteau’s scene of workmen putting away the old portrait of Louis XIV that had served as the sign for Gersaint’s shop, which was called “Au grand monarque.” In imagery, this signboard is remarkably close to the narrative that Watteau painted just a few years later. The parallels between the two works are so striking that one might be tempted to claim that the one was the basis for the other. Probably not the case, but clearly, there was a continuum for genre scenes and signs, one that deserves future investigation.

There are still other aspects of L’Enseigne that demand our attention. Of interest is the way in which the shape of the original signboard was transformed after it was demounted and taken into Gersaint’s shop. It is generally agreed that the picture’s lunette shape was changed to a rectangular one. As noted above, this was accomplished by cutting away small portions of the canvas at the lower outer corners and unfolding canvas that had been folded back at the top to create the lunette shape.

Our greater concern is the division of the composition into two parts. The painting would have been a considerable size if it had been painted on one continuous canvas—which is what Vogtherr and the Berlin conservators maintain. Certainly, the canvas would have been difficult to handle in the small quarters of Gersaint’s living quarters. The width of the building was only 3.56 meters in width, and 3.4 meters in depth. If the sign were made from one enormous canvas, matching the lunette-shaped space over the doorway, it too would have had the same width of at least 3.5 meters. Maneuvering a canvas of such unwieldly proportions in the restricted space of Gersaint’s interior would have been difficult. Two canvases of equal width, each measuring only 1.50 meters or a bit more, would have been more commodious for the ailing Watteau to have handled. A two-part signboard would not only have been more convenient but, in fact, was customary. The anonymous signboard for a draper's shop (fig. 14) has this two-part formula.

The design of L’Enseigne is itself quite telling. It reveals that the picture was conceived as two separate sections. Both the left- and right-hand sections have a semicircle of figures, each complete and self-absorbed. In the right half, the figures at the counter gaze at a mirror, while a couple at the back examine a large oval painting. All the figures in this right-hand section disregard the people in the left-hand portion. Likewise, the people in the left-hand section are grouped around the old sign being packed away, and not one is aware of what is transpiring as the right. As slight as his illustration for La Gallerie du palais is, Watteau took care to show a man at the left looking across to the figures at the right; this provides psychological interest and binds the two sides of the composition together. In the Enseigne the figures strike poses that emphasize the closed, semicircular nature of the groupings. For example, in the left-hand portion, the woman climbing the curb and the man helping her both arch their bodies in exaggerated curves, causing us to focus toward the left. The figures in the right half are all inclined to the right, just as those in the left half turn in the opposite direction. It is almost as though each group had an aversion to the other. These poses emphasize the division of the signboard into two, independent units, and demonstrate that the two parts were from inception intended to be separate. The central axis, the space between the two halves, intercepts no person or object of consequence. From the start, this central section was intended to be a neutral space, and to provide room for whatever framing elements were used on the signboard.

That L’Enseigne was created to be in two parts is not a new idea. It was advanced more than a half century ago by Hélène Adhémar but it did not gain traction.16 Moreover, Vogtherr has recently and specifically challenged her thesis. He claims that, “The exact analysis of the fabric edges of the two parts and the absence of tension garlands” disprove her thesis.17 Yet a visual analysis of the painting leads to the conclusion that it was conceived to be bi-partite.

|

15. Anonymous French artist after Watteau, Partial Copy after L’Enseigne de Gersaint, oil on canvas, 98 x 130 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

Vogtherr and his team believe that the painting was not cut in two until 1746 when it was in the hands of the Amsterdam art dealer Pieter Boetgens. Yet this supposition is challenged by copies of the signboard, evidently executed in France. A copy of the left-hand portion of L’Enseigne, already recorded in a 1769 Paris sale and last seen in the 1925 sale of the Michel-Levy collection, offers significant evidence that the painting was in two parts when it was still in Paris (fig. 15). It was evidently copied directly from Watteau's picture and was of comparable scale. Its high quality is such that in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries it was thought to be the original; some maintain, and not without reason, that it was executed by Pater.18 That the Michel-Levy painting copies just one side of Watteau's painting is striking. It is a telling witness to the bipartite nature of L’Enseigne. Moreover, and key to this argument, there also was a copy of just the right-hand side of Watteau’s painting. This picture was recorded in a Paris auction in 1829 but has not been seen since.19 Presumably it was the pendant to the Michel-Levy painting. These two copies help establish that Watteau’s painting was in two parts before it left the French capital and, in fact, was planned that way from the start. Two-part signboards were not unheard of, as shown by the signboard for a drape's shop (fig. 15).

When Watteau returned from London in 1720, he was ill and sought refuge with Gersaint. He painted this signboard to repay his friend for his kindness in taking him in. Also, the artist “wanted to stretch his fingers,” as Gersaint phrased it. As impromptu and spontaneous as Watteau’s token of friendship may have seemed, it was consistent with his prior work. He already had ample experience in painting them; the depictions of shop interiors were terra cognita for him. It was a natural choice. Yet as much as Watteau’s Enseigne de Gersaint was rooted in traditions familiar to him, he surpassed the established norms to create a universal masterpiece.

NOTES

1 The literature on L’Enseigne de Gersaint is immense. For recent treatments of the signboard, see Hélène Adhémar, “L’Enseigne de Gersaint, Antoine Watteau. Aperçus nouveaux,” Bulletin du Laboratoire du Musée du Louvre, 9 (1964), 7-18; Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art; Paris, Musée du Louvre; Berlin, Schloss Charlottenburg. Watteau 1684-1721, ed. Pierre Rosenberg and Margaret Morgan Grasselli, exh. cat. (Washington, D.C.: 1984), cat. P 73; Guillaume Glorieux. À l'Enseigne de Gersaint: Edmé-François Gersaint, marchand d'art sur le Pont Notre-Dame (1694-1750) (Mayenne: 2002); Christoph Martin Vogtherr et al., Französische Gemälde I, Watteau, Pater, Lancret, Lajoüe (Berlin: 2011), cat. 7.

2 Edme François Gersaint, “Abrégé de la vie d’Antoine Watteau” (1744), in Pierre Rosenberg, ed. Vies anciennes de Watteau (Paris: 1984), 37: “A son retour à Paris, qui était en 1721 dans les premières années de mon établissement, il vint chez moi me demander si je voulais bien le recevoir, et lui permettre, por se dégourdir les doigts, ce sont ses termes, si je voulais bien, dis-je, lui permettre de peindre un plafond que je devais exposer en dehors. J’eus quelque répugnance à le satisfaire, aimant beaucoup mieux l’occuper à quelque chose de plus solide; mais voyant que cela lui ferrait plaisir, j’y consentis.”

3 Ibid.: “L’on sait la réussite qu’eu ce morceau; . . . il attirait les yeux des passants; et même les plus habiles peintres vinrent à plusieurs fois pour l’admirer.”

4 This version of Watteau’s composition was included in Paris, Musée de la monnaie. Pèlerinage à Watteau, exh. cat. (Paris: 1977), cat. 209.

5 Nor did this tradition die with Gersaint’s signboard. One need only think of the splendid mid-eighteenth-century views of Roman art galleries by Giovanni Paolo Panini.

6 London, Sotheby’s, October 12, 1983, lot 5, attributed to Dutch school, c. 1720. Previously sold, London, Sotheby’s, May 30, 1956, attributed to William Hogarth.

7 Regarding this drawing, see Karl T. Parker and Jacques Mathey, Antoine Watteau, catalogue complet de son oeuvre dessiné, 2 vols. (Paris, 1957), 1: cat. 139; Martin Eidelberg, Watteau’s Drawings: Their Use and Significance, Ph.D. diss., Princeton University, 1965 (New York: 1977), 24, 38, 231, 236-45, 250, 252. Donald Posner, Antoine Watteau (Ithaca: 1984), 42, 273; Margaret Morgan Grasselli, The Drawings of Antoine Watteau: Stylistic Development and Problems of Chronology (Ann Arbor, MI: 1987), 398-99; Pierre Rosenberg and Louis-Antoine Prat, Antoine Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins, 3 vols. (Milan, 1996), 1: cat. 24.

8 One notable exception is Marianne Roland Michel, Watteau, un artiste au XVIIIe siècle (Paris: 1984), 116. While not totally rejecting the idea that the Louvre drawing was intended for a barber’s shop sign, she preferred instead to see it as a theatrical representation. But none of Watteau’s theatrical subjects are so rigidly structured. Moreover, by no stretch of the imagination can the draperies at the sides be understood as theater curtains.

9 Rosenberg and Prat have noted that the man looking at his reflection in the mirror on the back wall anticipates the motif of the woman and man examining a painting at the back of the room in the Berlin signboard. At best, this is a coincidental parallel.

10 See Marianne Paunet, Antoine Dieu (1662?-1727) (Paris: 2018), cat. 53. The seated lady at the left side of the drawing wears a fontange, a headdress concoted of lace that was in favor for this restricted period of time.

11 Parker and Mathey, Watteau, catalogue complet (1957) 1: cat. 140; Eidelberg, Watteau’s Drawings (1977), 231, 237, 245-52; Posner, Watteau (1984), 273, 276; Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 116-17; Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 cat. 1; Grasselli, Drawings of Watteau (1987), 30-32, 402-3; Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné (1997),1: cat. 87.

12 See Jacques Wilhelm, “Peinture et publicité,” L’Oeil, 37 (January 1958), 52, 54.

13 For this commission, see Martin Eidelberg, “Watteau’s Drawings for the Plays of Thomas and Pierre Corneille,” Master Drawings, 58 (Fall 2020), 333-42.

14 François Boucher, “Les Sources d’inspiration de l’enseigne de Gersaint,” Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire de l’art français (1957), 123-29. Martin Eidelberg, Watteau’s Drawings: Their Use and Significance, Ph.D. diss., Princeton University, 1965 (New York: Garland Press, 1977), 250-51.

15 Paris, sale, Hôtel Drouot, January 11, 2019, lot 13.

16 Adhémar, “L’Enseigne de Gersaint“ (1964), 9.

17 Vogtherr, Französische Gemälde (2011), 198.

18 The primacy of the Michel-Levy painting prevailed, especially among French scholars. The tide of opinion changed after the Germans publicly exhibited Watteau’s painting, which until then had been hidden from most visitors’ sight in a bedroom

19 Paris, sale, Francillon collection, May 12ff, 1829, lot 157: “(WATTEAU (ANTOINE) . . . Le cabinet d’un marchand de tableaux. Dans une salle ornée de peintures, une jeune femme assise à son comptoir, présente à une dame un petit tableau qui selle-ci regarde avec beaucoup d’attention. Un autre tableau posé à terre occupe particulièrement les regards de plusieurs amateurs, dont l’un s’est agenouillé pour le mieux voir. Nous avons etendu dire que cet ouvrage fut fait pour Gersaint, et servait d’enseigne à son magasin.” This picture, rather than the one later in the Michel-Levy collection, may have figured in a Paris sale, May 28-31, 1850, cat. 62: “DU MÊME [WATTEAU] . . . La moitié de l’Enseigne. Tableau en plafond, fait pour son ami Gersaint, marchand sur le pont Notre-Dame. Avec sa Gravure.”