The Jovial Master

© Martin Eidelberg

Created July 2020

© Martin Eidelberg

Created July 2020

Among the literally hundreds of paintings wrongly attributed to Watteau, certain ones attract us, for although they may not be by the master, they have a compelling charm. Within this large, amorphous body of anonymous works some display a distinct, separate character and clearly announce their maker, whoever he may be. The artist to be discussed here and whom we have named “The Jovial Master,” worked in Paris in the decades after Watteau’s death in 1721. But, unlike Watteau, the master of elegiac love and muted music, the creator of poetic elegance, our painter is robust, exuding an excess of mirth and gaiety, as well as burlesque movement. Although “The Jovial Master” is not the typical appellation used to designate an anonymous painter, it well conveys his spirit.

A good starting point is a pair of paintings that in the mid-nineteenth century were in the collection of Lambert Devère, “ancien officier supérieur d’État -Major.”1 We know very little about the collector but we know something about his collection, part of which was sold in 1859. He owned seven paintings that were given to Watteau, a considerable number at a time when the collecting of rococo art was not yet in favor. Whether any were actually by Watteau is only a secondary concern. Six featured commedia dell’arte characters, and of particular interest are the first and second entries under Watteau’s name:

Watteau . . . La balançoire. Panneau. Ovale.

` Watteau . . . L’escarpolette. Pendant du précedent.

|

|

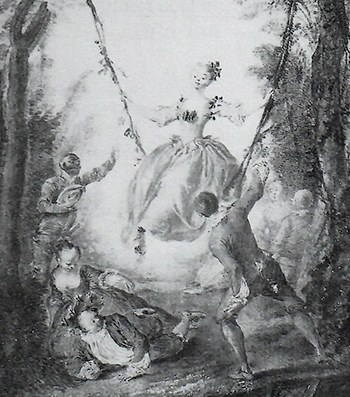

1. The Jovial Master, L’Escarpolette, oil on panel, 41 x 36 cm. Paris(?), private collection. |

2. The Jovial Master, La Bascule, oil on panel, 41 x 36 cm. Canada, private collection. |

Despite the sparse descriptions, these two pictures can be identified with extant works (figs. 1, 2). Both are oval panels with the requisite themes. In L’Escarpolette, a young girl happily swings on a simple rustic swing, pulled forward by a young man. At the left, Harlequin salutes her, and in the foreground, adding to the excitement, a young man has fallen down and is ministered to by a solicitous woman. In the pendant picture, a young couple in the foreground exchange words of love, while in the background couples fall off the see-saw, their legs thrashing in the air. Behind, Pierrot tranquilly watches them. These games of love became a favorite theme for French painters, attracting Watteau’s followers more so than their master.

Just a few years later, in 1861, these two paintings reappeared in the sale of the collection of the comte de Monbrun.2 They were still attributed to Watteau, but now with full descriptions and even notation of color. L’Escarpolette (now called La Balancoire) sold for 2,000 francs, whereas the so-called Jeu de Bascule sold for only 1,000 francs. Apparently they were sold to different buyers. Whereas La Bascule cannot be traced again in the nineteenth century, L’Escarpolette reappeared at the very end of the century: in 1892 it was sold from the collection of Anatole-Auguste Hulot.3 L’Escarpolette next entered the noted collection of Edouard André, formed with his wife Nélie Jacquemart. André died in 1894 but the collection remained intact, and L’Escarpolette was photographed in situ in 1912 as part of the Jacquemart-André collection. But a photo taken just a year later reveals that it had been removed. In the recent exhibition, De Watteau à Fragonard at the Jacquemart-André Museum, the museum’s director bemoaned the painting’s unexplained disappearance and, surprisingly, he still believed that the painting was by Watteau.4 The painting’s disappearance is easily explained: Nélie Jacquemart died in 1912, and while most of the collection remained intact, she left the so-called Watteau to comte Cornudet (probably to be identified with Joseph-Honoré-François Cornudet de Chomettes; 1861-1938). When he lent the picture to an exhibition in Amsterdam in 1926, it still was listed under Watteau’s name.5 In 1988, it figured in the sale of the collection of Georges Renand, and this time its old attribution to Watteau was replaced by an ascription to the relatively minor painter Sébastien Jacques Leclerc, known as Leclerc des Gobelins.6 The accompanying phrase “attribué à” suggests the tentative nature of this reattribution and, indeed, it is not at all convincing.

Far less is known of the history of the pendant, La Bascule. Its whereabouts in the second half of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth have not been traced. It emerged in a private Canadian collection after World War II and, as far is known, may still be there.

Although the two paintings have been consistantly presented as independent easel paintings, it is evident that they were conceived as decorative panels. The small platforms on which the characters stand and the diaper-patterned front sides of the platforms conform to the tradition of ornamental arabesques in the early eighteenth century. At the same time, the fullness of the landscapes and the emphasis on pictorial qualities, as opposed to the formal elements of traditional arabesques, is a natural evolution from Watteau’s approach to such decorative projects.

|

|

3. The Jovial Master, L’Escarpolette, 24 x 29 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

4. The Jovial Master, L'Escarpolette (detail of fig. 1). |

Closely linked to L’Escarpolette is a painting with a woman on a swing that I know only from an old photograph (fig. 3). According to the inscription on the verso, it was owned by K.T. Bachketz (the name is not totally legible) of Berlin. Its composition is essentially a reduction of the previous work, eliminating three of the figures and keeping just the woman on the swing and the man who has fallen on the ground. Although the two characters are almost identical to their counterparts in L’Escarpolette, some minor changes—such as the position of the man’s legs—were introduced. However, the style of the painting, especially the distinctive smiling faces, remains unchanged. This artist well deserves the epithet “jovial.”

Another work that can be given to our anonymous master is a picture that came up at German auctions in 2013 and 2016, attributed to a follower of Watteau (fig. 5).7 It shows six commedia dell’arte characters grouped beneath a term figure of a young woman. Mezzetin lies on the ground and a young actress looks down at him. Hat in hand (a characteristic pose for this character), Pierrot bows to Mezzetin, and in the background, hidden in the shadow, Harlequin gestures. The body types, especially the large, round heads and the now-familiar smiles mark this as a work of the Jovial Master. Mezettin’s active gesticulation, his angled body jutting toward us, is one of the artist’s recognizable characteristics but in this instance it may not entirely be his invention. Rather this figure depends heavily on an invention inspired by Watteau. This distinctively posed actor seems to have been based on the figure in the foreground of Watteau’s L’Accord parfait (fig. 6). However, the Jovial Master introduced changes: whereas Watteau positioned the actor’s body parallel to the picture plane, the Jolly Master turned the figure at a steeper angle and included the legs to emphasize this directional vector; similarly he made the actor’s arms more active, almost violent. This comedian is less like Watteau’s figure and more like the figures flailing about in the background of La Bascule.

|

7. The Jovial Master, Embarkation for Cythera, oil on panel, 66.5 x 43.5 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

|

8. Antoine Watteau, Pèlerinage à Cythère, oil on canvas, 129 x 194 cm. Paris, Musée du Louvre. |

A fifth addition to the oeuvre of the Jovial Master is his version of a Pèlerinage à Cythère (fig. 7). In the wake of the success of Watteau’s reception piece for the Academy (fig.8), it was only natural that this new subject would be emulated by his followers. Pater and Lancret painted a few examples, and Quillard executed at least five. The Jovial Master joined this company, as can be seen in a painting that has appeared on the art market a number of times, most often attributed to Watteau or members of his school, including Quillard.8 Unlike the suave, gentle figures in Watteau’s painting, here the figures are more robust and even humorous. The heavy-set woman at the right, listening to the entreaties of her companion, has a round face and curving eyebrows, and grins in the mode so typical of the Jovial Master. Her kneeling companion strikes a contorted pose equally characteristic of our painter.

The few paintings that we have assembled here form a homogeneous body of work that establish this artist’s presence. In lieu of textual documents, these paintings offer the means of writing his biography. The paintings were probably executed in the 1720s and ‘30s, which suggests that the artist was born c. 1700; Watteau’s satellite Pater was born in 1695; Lancret in 1690. The limited number of works we have found suggest that he may have had limited success and few commissions, or he may have died relatively young. In any event, they do not hold out the hope that we will discover a substantially larger corpus or find his proper name. But despite that, the Jovial Master will survive, even if only as a concept.

NOTES

1 Paris, sale, March 11, 1859 (Lugt 24721), cat. 20, 21. Aspects of the provenance of these two paintings are discussed in Émile Dacier, Jacques Vuaflart, and Albert Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs de Watteau au XVIIIème siècle, 4 vols. (Paris: 1921-29), 3: under cat. 40, 67. However, the authors dispersed the various sale references among others relating to different pictures.

2 Paris, sale, Hôtel des comissaires-priseurs, February 4-7, 1861 (Lugt 25979), collection of the comte de Monbrun, lots 43-44.

3 Paris, sale, Galerie Georges Petit, May 9-10, 1892 (Lugt 50806), Anatole-Auguste Hulot collection, lot 125.

4 Nicolas Sainte-Fare Garnot, “Reflexions sur L’Escarpolette d’Édouard André,” De Watteau à Fragonard, exh. cat. (Paris: Musée Jacquemart-André, 2014), 26-29.

5 The painting is cited in Carnudet’s collection in Louis Gillet, Watteau (Paris: 1921), 26, 151. See also Amsterdam, Stedelgh Museum, Exposition rétrospective d’art français (1926), cat. 117.

6 Paris, sale, Hôtel Drouot Montaigne, May 31, 1988, lot 21.

7 Stuttgart, sale, Nagel Auktionen, October 10, 2013, lot 729: Follower of Jean Antoine Watteau, Galante Szene im Park; also Rudolstadt, sale, Auktionshaus Wendl, October 20, 2016, lot 1551, in the style of Watteau, Park Scene.

8 Versailles, sale, Trianon, March 14, 1962, attributed to Quillard; Paris, sale, Palais d’Orsay, June 23, 1978, lot 22. The painting is also reproduced in Jean Ferré et al, Watteau, 4 vols. (Madrid: 1972), 2: cat. P 23, where it is assigned to the French school, eighteenth century.