Philippe Mercier, Watteau’s English Follower

© Martin Eidelberg

Created October 24, 2013

Click to Print or Download PDF Version

Philippe Mercier (c. 1689-1760) looms large in the history of English eighteenth-century art. One of the first practitioners of the new rococo style, Mercier’s genre subjects and portraits provided the foundation for William Hogarth and the next generation of English artists. In turn, Mercier owed much to the art that had preceded him, especially French painting. Notwithstanding that he was only five years younger than Antoine Watteau, he was one of his master’s so-called “satellites.” Indeed, his early works not only bear the imprint of the new Parisian style and subject matter but, as will be seen, reveal a direct contact with Watteau.1

There has been much scholarly interest in Mercier in recent times. After an initial attempt by Robert Rey around 1930, Robert Raines took up the challenge in the postwar years with greater success, and other secondary studies appeared as well.2 A catalogue raisonné of Mercier’s work published by Raines and John Ingamells in 1969 was accompanied by a major monographic exhibition at York and Kenwood.3 I compiled a catalogue of Mercier’s drawings in 2006.4 Nonetheless, very basic questions await resolution. The actual nature of Mercier’s association with Watteau is without doubt one of the most intriguing topics still to be tackled, and that is the subject to be considered here.

The critical issue of when and how the two men met has never been settled satisfactorily. Discussions have been left in large generalities, often clouded by erroneous suppositions. Unfortunately, no pertinent documents have been uncovered but, as will be seen, an analysis of the two men’s drawings and paintings suggests that Mercier and Watteau first met in Paris around 1715. Later, when both men were in London between late 1719 and mid 1720, they undoubtedly resumed their acquaintanceship. Mercier continued to travel to Paris and was directly involved with Watteau’s art even after his French master’s death in July 1721. My primary concern here, however, is restricted to their first meeting in Paris around 1715.

Any inquiry about Mercier is complicated by the circumstances of his family history and early training. Although of French blood (as it would have been expressed in the eighteenth century), Mercier was born in Berlin. His Huguenot parents had sought refuge in Prussia, where Mercier’s father successfully practiced his skill as a tapestry weaver. Thus the young Philippe probably spoke both French and German as a child. He reputedly studied first with his father and then trained under or, more likely, worked with Antoine Pesne, a French-born artist at the court of Frederick I of Prussia. As Raines has wisely pointed out, Mercier was already twenty-one years old when Pesne first arrived in Berlin in 1710, and so it seems more likely that he worked as an assistant, rather than as an apprentice, to Pesne. According to George Vertue, one of the most valuable sources of information about painting in England in the early eighteenth century, Mercier traveled to Italy and France before settling in London. This would have been in the mid 1710s, since Vertue recorded that Mercier first arrived in England about 1716 with a portrait of the Hanoverian prince Frederick Louis, the son of the future King George II of England.5 Both Vertue and Mercier were members of the Virtuosi of St. Luke and thus Vertue’s information about Mercier can be presumed to have come directly from the artist.

Mercier was soon settled in London. On July 17, 1719, he married Margaret Plante at St. Martin’s-in-the-Fields and thereafter began a family. Thus, when Watteau came to London in the last months of 1719, the newly-married Mercier was already established in the English capital. Some scholars have proposed that Mercier served as Watteau’s host. Others have strongly refuted the idea, but without any more proof than those who have affirmed it.6

|

|

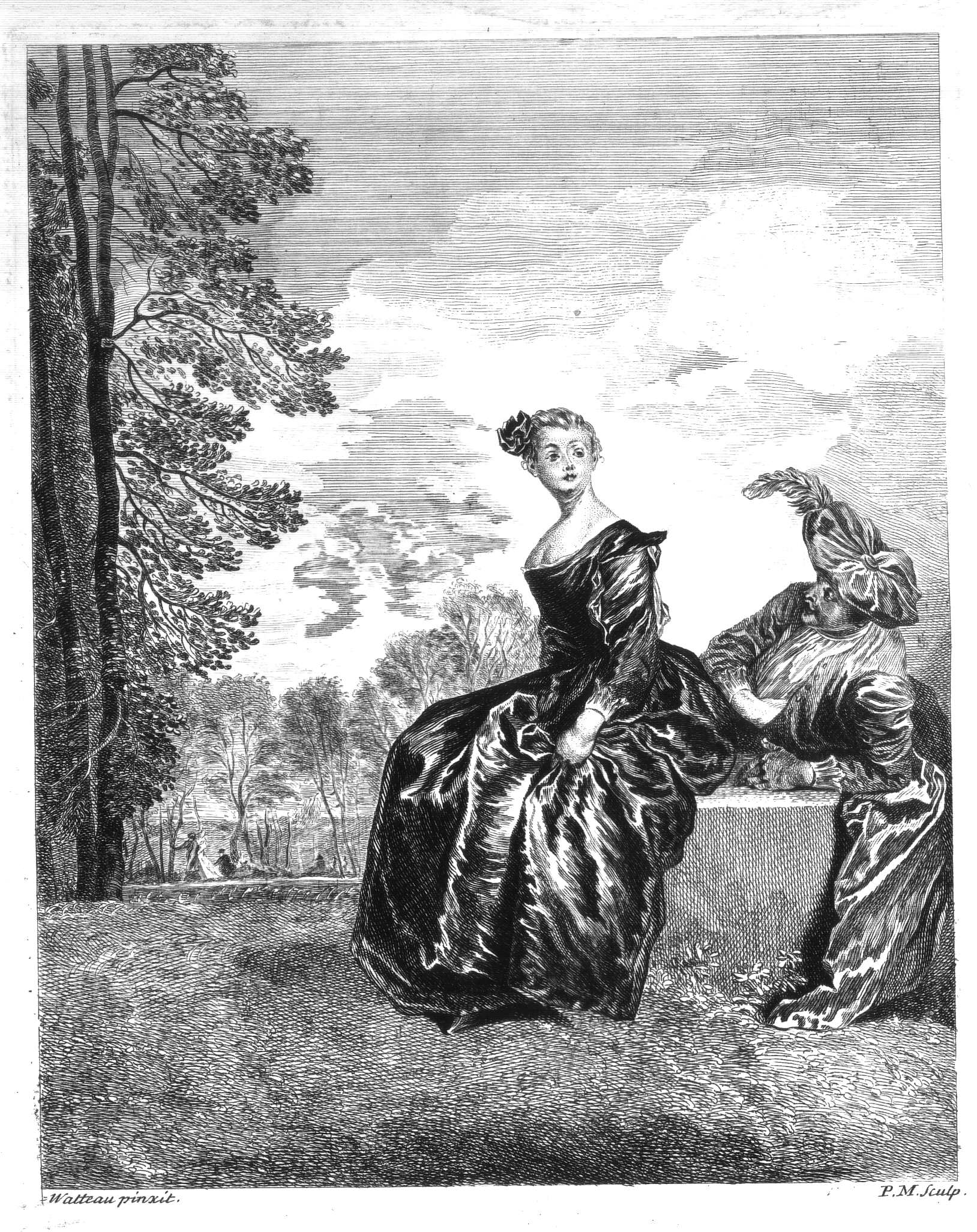

| 1. Philippe Mercier after Watteau, La Boudeuse, etching, 29.4 x 23.6 cm. London, The British Museum. | 2. Philippe Mercier after Watteau, L’Île de Cythère, etching, 46.4 x 55.3 cm. London, The British Museum. |

By the early 1720s Mercier was active as a painter and occasional printmaker. His fêtes galantes, as will be discussed in greater detail below, often depended on Watteau’s inventions. Likewise, his etchings reflected the French master’s manner, and some reproduced known Watteau compositions. He etched Watteau’s La Boudeuse, L’Île de Cythère, La Toilette intime, and La Leçon d’amour—all of which paintings are accepted by scholars as genuine works by Watteau (figs. 1-2). The print after La Leçon d’amour was dedicated to the comte de Caylus, the great French amateur of the arts and close friend of Watteau. Caylus visited London in 1722-23—providing yet another link between Mercier and Watteau’s circle, although by then Watteau himself was dead.

Complicating the situation are Mercier’s etchings after his own paintings but inscribed as though they were after Watteau’s inventions. Le Danseur aux castagnettes, La Promenade, L’Amant repoussé, La Colation, Le Triomphe de Vénus, and La Troupe italienne en vacances fall into this category (fig. 21). Despite their captions proclaiming Watteau’s name, scholars today are divided as to who executed the original pictures.

A related aspect of Mercier’s London career was his activity as a dealer in paintings and prints—a not uncommon means of income for artists in that age. The sole surviving evidence of his endeavors in this field is a catalogue for an auction held in London on April 21, 1724.7 It describes “A Very Valuable Collection of Fine Pictures by the Most Celebrated Italian, French and Flemish Masters. Collected abroad, by Mr. Mercier.” Presumably these were pictures which Mercier had recently brought back from the Continent, thus implying a trip about which we had not known. Included in this sale were a large number of French paintings and engravings of relatively recent vintage. Most intriguing of all is lot 72: “A Conversation, by Vatteau.” The fact that Mercier was evidently trying to palm some of his paintings off as genuine works by Watteau throws into question whether this lot was a painting truly by Watteau or one of Mercier’s own imitations. Unfortunately, the generic description and lack of measurements make it impossible to identify the picture and resolve the issue. The 1724 sale is recorded through the chance survival of a unique copy of the auction catalogue, now in the Frick Art Reference Library in New York. Like so many other English catalogues from this early date, it is just a single sheet, folded in half to create four pages. These early English catalogues were highly ephemeral in nature, and it is evident that many did not survive at all.8 Thus the extent of the activities of Mercier and other contemporary London art dealers remains largely hidden from sight. Whether Mercier assembled other such collections for auction is uncertain.

|

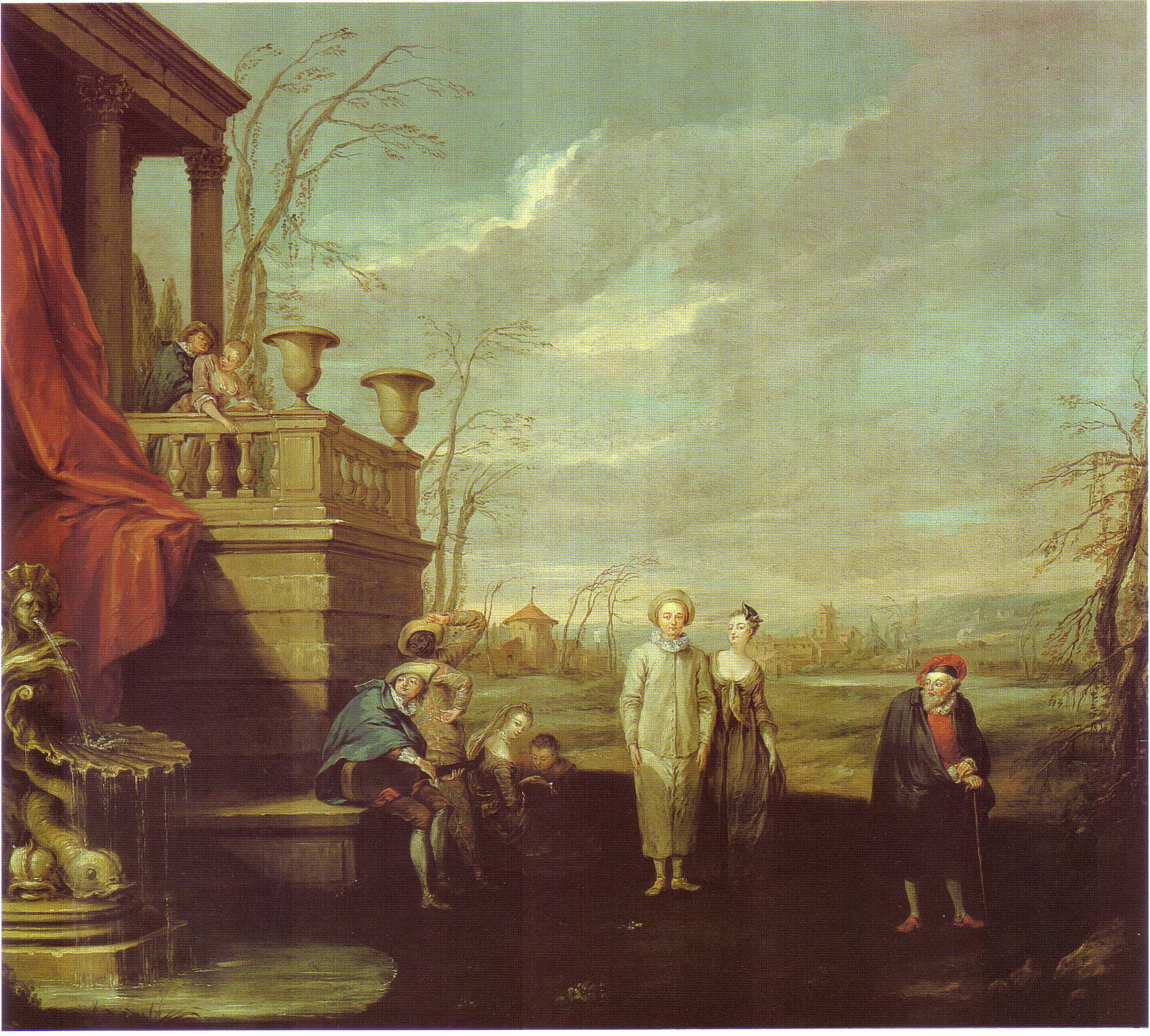

3. Here attributed to an anonymous French artist, Scene with Commedia dell’Arte Characters, oil on canvas, 63.5 x 76.2 cm. Wilton, Wilton House, Earl of Pembroke collection. |

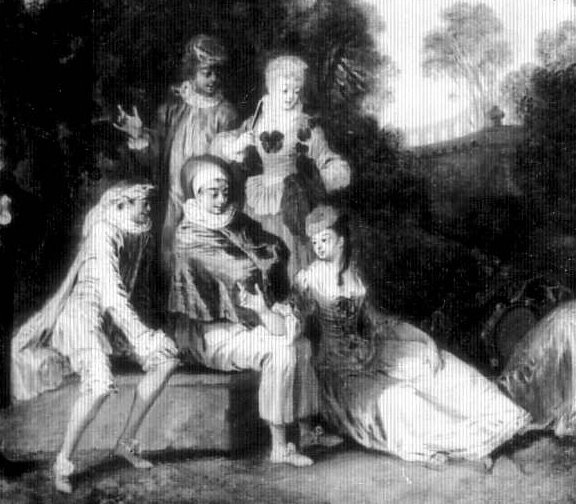

Much of our present understanding of Mercier’s relation to Watteau’s art is based upon a large group of paintings attributed to the English artist. An often-cited example is a composition with half-length commedia dell’arte characters in the collection of the Earl of Pembroke at Wilton House, often but erroneously entitled Musical Family (fig. 3).9 It was in the Pembroke family’s possession as early as 1731, but they had bought it, probably in the preceding decade, as a Watteau painting. Such chicanery was common in England, when many paintings falsely given to Watteau passed on the London market. The picture was listed under Watteau’s name in Carlo Gambarini’s 1731 catalogue of the Pembroke collection and although the Pembroke painting never figured in the canonical literature on Watteau, the official attribution was not changed until after it was cleaned in 1961 and Martin Davies ascribed it to Mercier.10 His reattribution has been retained by all subsequent scholars.

|

|

| 4. Louis Surugue after Antoine Watteau, La Leçon de musique. | 5. Antoine Watteau (?), Les Habits sont italiens, oil on canvas, 29.8 x 22.5 cm. Waddesdon (Buckinghamshire), Waddesdon Manor. |

Yet, even if not by Watteau, the components of the Pembroke picture were borrowed from well-known Watteau compositions.11 The woman at the left, reading from a song book, and the two charming children at her side were taken from Watteau’s La Leçon de musique, not from the painting now in the Wallace Collection but from the 1719 engraving by Louis Surugue in the Jullienne Oeuvre gravé (fig. 4).12 The female Harlequin and her fellow actress are from Les Habits sont italiens, a version of which is at Waddesdon Manor (fig. 5).

|

|

| 6. Bernard Baron after Watteau, L’Amour paisible (detail). | 7. Charles Nicolas Cochin after Watteau, Iris, c’est de bonne heure. |

The lute player, the woman seated on the ground, and the standing woman seen slightly from behind are all taken from L’Amour paisible (fig. 6). Finally, the small figures in the far right background—the standing girl, the flutist, and his companion—are all taken from Iris, c’est de bonne heure. They were borrowed not from the Watteau painting now in Berlin but from the engraving by Bernard Baron, as is shown by the reversed direction of the painted figures (fig. 7). Thus, the picture could not have been painted until after the print’s release, sometime between 1726 and 1729.13

For many scholars, this sort of piecemealed pastiche has come to typify Mercier’s early modus operandi. The emphasis has been on Mercier’s appropriations of disparate elements from Watteau’s compositions and his transformation of them into new compositions. Frederick Antal went so far as to characterize Mercier as “a forger of Watteau.”14 A more moderate view was expressed on several occasions by Ingamells and Raines. For example, Raines described Mercier’s “too eclectic approach, his too ready acceptance of influences and themes and figures which his artistic personality was not always strong enough to transmute.”15 Elsewhere, Raines and Ingamells characterized the work from Mercier’s earliest period as “engravings and pastiches of Watteau.”16 Raines termed the Pembroke picture “the key to Mercier’s approach to Watteau,” and then proceeded to dissect its sources.17 Nicole Parmantier selected the Earl of Pembroke’s painting to illustrate that “… Mercier knew Watteau’s works. His paintings amply demonstrate it.”18 Similarly, Brian Allen singled out the Pembroke painting as being “typical of the sort of work by Mercier that often passed as that of Watteau.”19

|

| 8. Here attributed to an anonymous English artist, Commedia dell’arte Actors on a Terrace, oil on canvas, 104. X 118 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

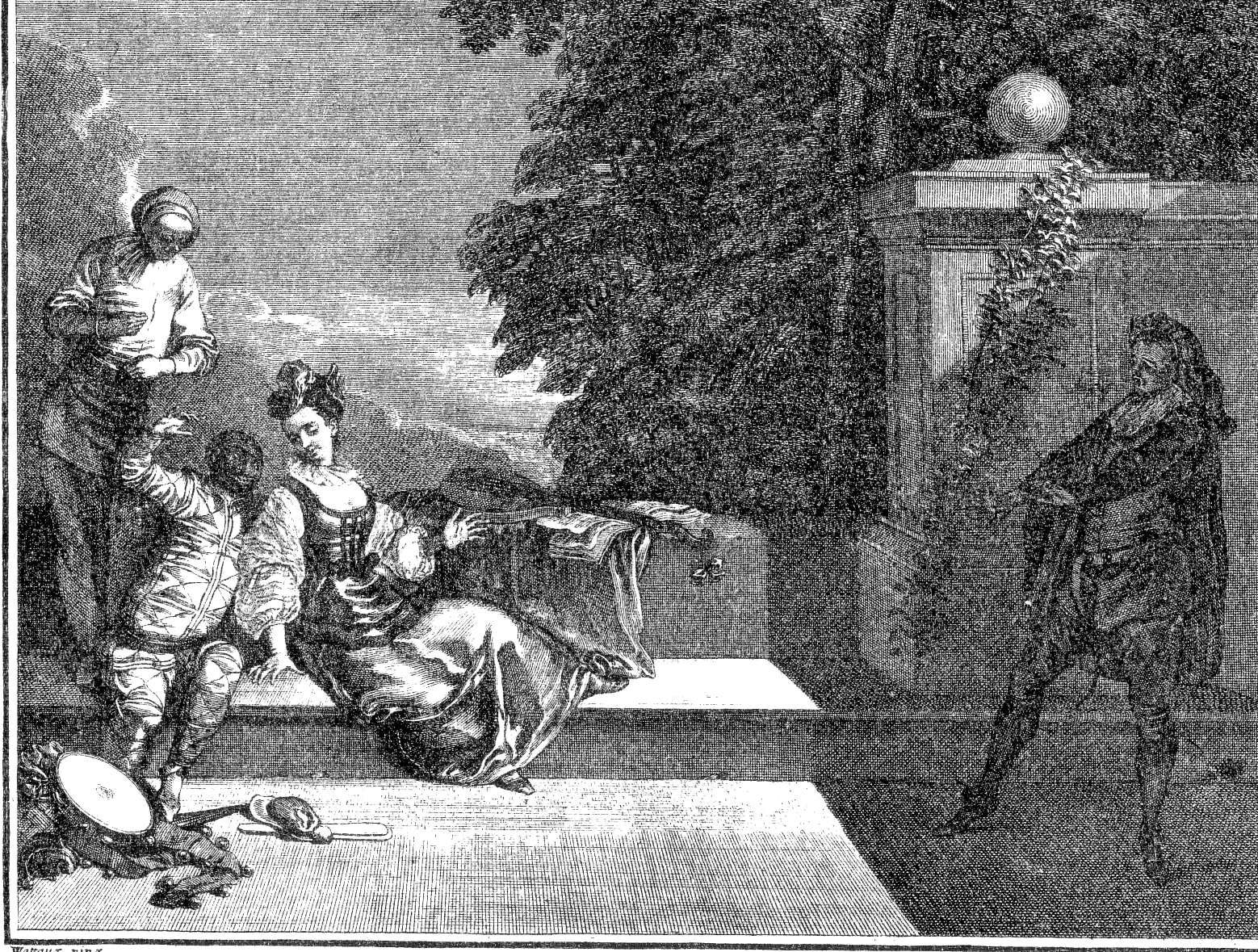

Our sense of Mercier as a clever plagiarizer and sly forger of Watteau’s paintings is reinforced by a number of other such paintings. One is the Commedia dell’arte Actors on a Terrace, a picture that appeared at auction several times in the last few decades (fig. 8). Like the Earl of Pembroke’s painting, it too has an English provenance, having been in the collection of the Mainwaring family of Oteley Park.20 Probably while at Oteley Park and certainly by the time it left for the United States in the early twentieth century, the picture bore an attribution to Watteau.21 In recent decades the painting was downgraded to merely an anonymous French eighteenth-century artist and then, about twenty years ago, was upgraded and attributed to Mercier.22 Although the painting did not appear in Ingamells and Raines’ catalogue of Mercier’s works, Ingamells accepted it by 1991.

| 9. Antoine Watteau, Les Comédiens italiens, oil on canvas, 63.8 x 76. 2 cm. Washington, National Gallery of Art. |

The Commedia dell’arte Actors on a Terrace is a large work but the figures are relatively small in scale in relation to the overall composition. The five principal figures can be traced to Watteau: at the left a Mezzetin with his guitar, Harlequin, Pierrot coupled with Flaminia, and, lastly, the Bolognese Doctor at the far right. All five characters were taken from Watteau’s Comédiens italiens (fig. 9). There they loom large and monumental and are backed by a strong architectural framework. On the other hand, the characters in the Oteley Park painting are diminutive, especially in relation to the extensive, airy environment. Likewise, whereas Watteau grouped the actors together closely in a meaningful narrative, the Otelely Park painting shows them spaced apart and without any psychological relationship. Thus, while copying something of the form of Watteau’s painting, it lacks the spirit and intent of Watteau’s narrative.23

|

| 10. Here attributed to an anonymous artist, Fete galante, oil on canvas, 46.5 x 36 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

A third and often-cited example of Mercier’s indebtedness to Watteau is a fête galante formerly in the collection of the Duke of Northumberland at Syon House (fig. 10). In the mid-eighteenth century the picture hung in the first duchess’s bedroom and was attributed to Mercier. His authorship was still in place when the picture was sold at auction in London in 1952, and again in Paris in 1974.24 The attribution to Mercier was also upheld by Ingamells and Raines.25

|

|

| 11. Charles Nicolas Cochin after Watteau, Le Bosquet de Bacchus (detail). | 12. Jean Philippe Le Bas after Watteau, L’Assemblée dans un parc (detail), engraving. |

Here too, the painting is a compilation of elements from two Watteau compositions. The man and woman promenading at the left, as well as the fountain sculpture of Bacchus, are taken without change from Watteau’s fête galante, Le Bosquet de Bacchus, a picture recorded in an engraving in the Jullienne Oeuvre gravé (fig. 11). The five smaller figures in the background are from Watteau’s Assemblée galante, also recorded in an engraving in the Jullienne Oeuvre gravé (fig. 12). Given the left-right orientation of the figures in the ex-Northumberland painting, it is evident that they were borrowed not from Watteau’s original paintings but from the two prints. Since Le Bas’s engraving after L’Assemblée galante was not announced until November 1731, and Cochin’s engraving after Le Bosquet de Bacchus was not available until December 1731, that means that the Northumberland painting could not have been executed until 1732 at the earliest.26

Dozens of such paintings, all based on Watteau’s compositions, have been ascribed to Mercier.27 Some are direct transcriptions of entire Watteau compositions, others are pastiches bringing together sundry Watteau groups. They may be based on his paintings or the Jullienne engravings or perhaps a combination of both types of sources. All these pictures reinforce the negative view of Mercier’s work as a plagiarist, but there is one inconvenient truth: none of them are actually by Mercier. Certainly the paintings from the Earls of Pemberton, the Mainwaring family, and the Dukes of Northumberland not only have no stylistic resemblance to works demonstrably by Mercier but they have no stylistic relation to each other. That some of them, such as the one from Syon House, bear old ascriptions to Mercier is no more compelling than the equally old but equally false attributions to Watteau. Martin Davies’ reattribution of the Pembroke painting to Mercier, like the similarly recent reattribution of the Oteley Park painting, were instituted only when the old ascriptions to Watteau proved untenable. Perhaps Davies, searching for a possible name, thought he saw a general resemblance between the Pembroke painting and Mercier’s later half-length genre scenes but, if so, he was deceived. Ascribing these Watteau look-alikes to Mercier (and other Watteau satellites) is an expedient and all too common phenomenon.28

Clearly, the corpus of Mercier’s early paintings in the manner of Watteau needs to be rethought. A more logical basis for assigning works to him should be established. A good measure of Mercier’s early style under the influence of Watteau, is found in several compositions that the artist himself etched. Those that proclaim “PM pinxit” and even some that falsely claim “Watteau pinxit” reveal mannerisms of style that allow us to identify his hand with greater confidence.

|

| 13. Philippe Mercier, L’Heureuse rencontre, oil on canvas, 35 x 30 cm. California private collection. |

An excellent starting point is a painting in an American private collection that is known as L’Heureuse rencontre (fig. 13). It features an elegantly posed man and woman momentarily stopped as they stroll in a garden.

|

|

| 14. Philippe Mercier, L’Heureuse rencontre, etching. London, British Museum. | 15. Antoine Watteau, La Cascade, oil on canvas, 41 x 31.9 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

That this painting is actually by Mercier is assured by the artist’s etching, which is captioned “P Mercier Pinxit et Sculpt” (fig. 14).29 As has often been noted, the overall composition and particularly the central couple recall certain Watteau models such as La Cascade (fig. 15). The trees with their feathery, sweeping branches recall Watteau’s approach to landscape, and the screen of trees across the distant background in Mercier’s painting is comparable to the similar arrangement in Watteau’s paintings such as La Boudeuse, a work that Mercier knew and etched (fig. 1).

|

|

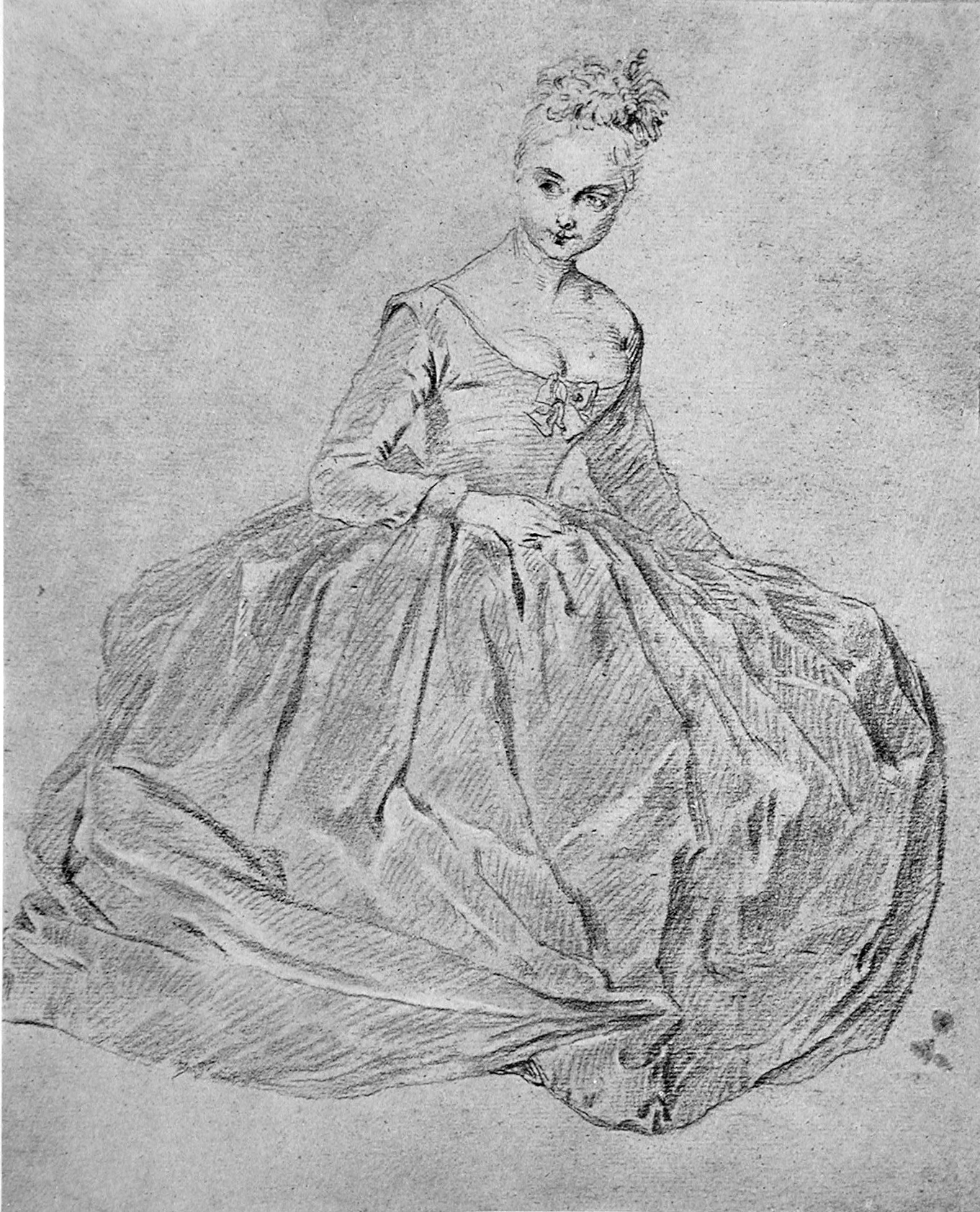

| 16. Philippe Merceir, L’Heureuse rencontre (detail). | 17. Philippe Mercier, Study of a Woman Seated on the Ground, red and black chalk, 29.5 x 24.5 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

But if L’Heureuse rencontre is Watteau-like, certain elements distinguish this work from Watteau. Most noticeably, the proportions of Mercier’s figures are different. In particular, the heads are slightly larger than they should be (fig. 16). Also, the necks, both of the standing woman and the seated woman at the right are tubular. The structures of the faces are different: the eyes bulge, the lachrymal sacs are pronounced, and the eyebrows are slightly arched. Together, they create a slightly quizzical look that is far removed from the generally languid expressions of Watteau’s characters. These features mark Mercier’s work and, as will be seen, are present in his other pictures from this stage of his career.

Unlike the works that will be discussed below and which are earlier, L’Heureuse rencontre does not seem to have specific borrowings from Watteau. This can probably be attributed to his growing use of his own studies from the live model from the mid 1720s onward.30 A quite charming study of a woman seated on the ground, once in the collection of James Charles Robinson, was used for the lady at the right of the painting (fig. 17). Similarly, a drawing of a sleeping woman, now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Springfield, Massachusetts, was used for the woman asleep at the left side of Mercier’s picture. Although very few of Mercier’s drawings have survived, they are a key to understanding his mature work and his increasing independence from Watteau’s direct influence.

| 18. Philippe Mercier, Courting Couple, oil on canvas, 34.9 x 29.8 cm. Whereabouts unknown. | 19. Philippe Mercier, Courting Couple (detail). |

Another Mercier painting from this moment, also in the manner of Watteau but without elements borrowed directly from the French master’s works, is a picture formerly in the collection of Lady Sutherland (fig. 18).31 Lest there be any doubt of Mercier’s authorship, an otherwise unrecorded etching by Mercier, made after this composition, was in the possession of John Ingamells.32 Not only are the overall narrative and quality of the figures in the painting far removed from Watteau, but also the specific features of the characters are wholly in accord with what we have identified as Mercier’s style (fig. 19). The head of the male suitor is proportionately large, his eyes are too prominent, the eyebrows have that particular arching quality and, as a result, his expression is intent. The bald man standing behind the bench has these same features, perhaps even more pronouncedly. As might expected in a Mercier painting, the woman being courted has too long a neck, a large head, recessive chin, as well as the typical expression of the eyes. This painting—like L’Heureuse rencontre—reinforces the stylistic standards by which an attribution to Mercier can be judged.

|

|

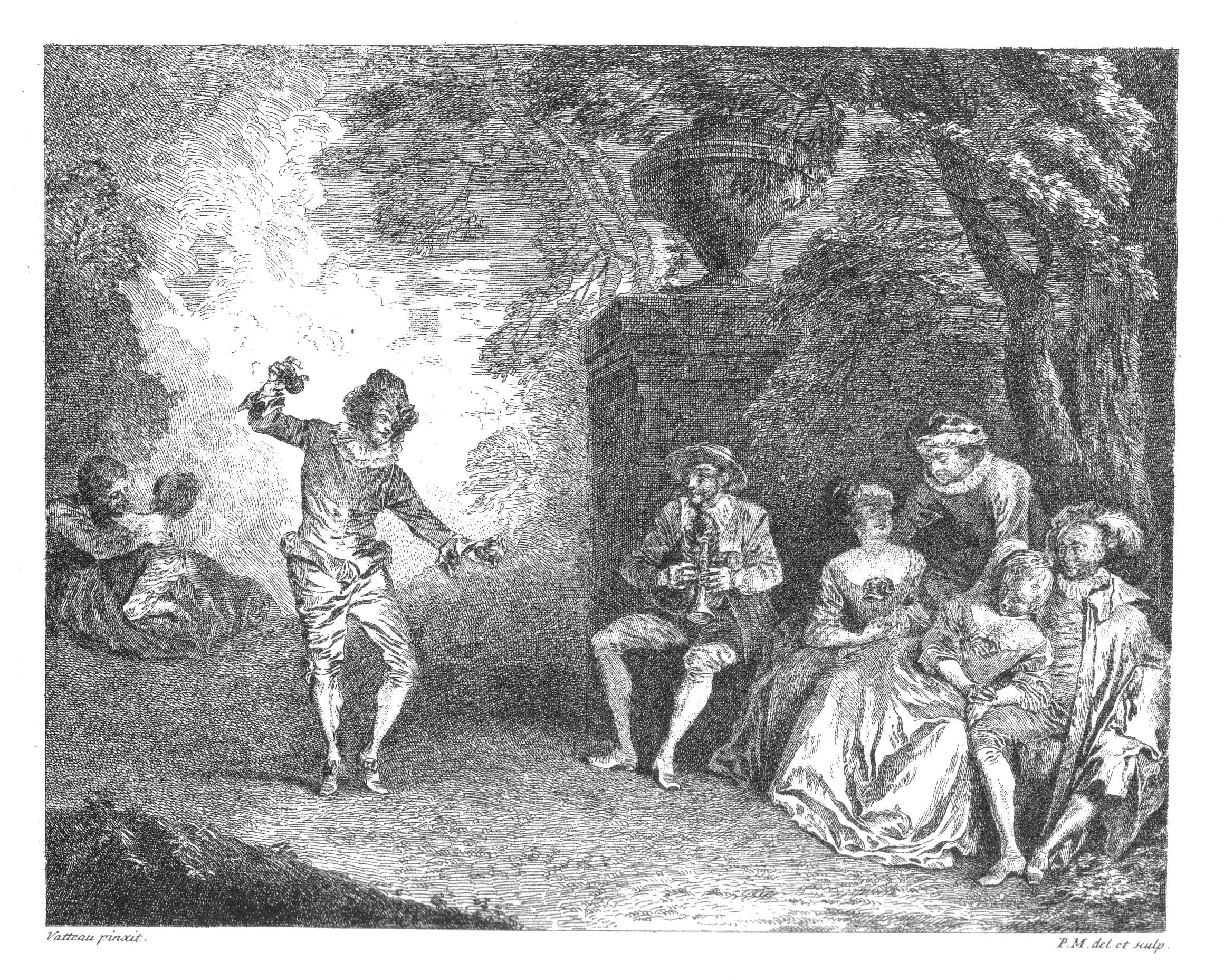

| 20. Philippe Mercier, Le Danseur aux castagnettes, oil on canvas, 28 x 35 cm. Whereabouts unknown (formerly New York, Harold D. Wimpfheimer collection). | 21. Philippe Mercier, Le Danseur aux castagnettes, etching, 31.8 x 37.5 cm. London, British Museum. |

With this in mind, we should turn to some other early Mercier paintings whose occasional, often tentative ascriptions to Mercier can now be reaffirmed. These pictures contain important clues regarding the artist’s early working method and the way in which he approached and assimilated Watteau’s art. A key work is a fête galante formerly in the collection of Harold D. Wimpfheimer of New York (fig. 20).33 Known as Le Danseur aux castagnettes, this composition was etched by Mercier, in 1723 according to Jean Pierre Mariette (fig. 21).34 Although the print bears the problematic caption “Watteau pinxit,” modern critics agree that the painting is not by Watteau, and some have conceded that it was fully conceived and executed by Mercier.35

|

| 22. Philippe Mercier, Fête galante, oil on canvas, 73.7 x 91 cm. Whereabouts unknown (formerly Paris, Galerie Segoura). |

A second work to be added to this group is a fête galante once with the Parisian dealer Maurice Segoura (fig. 22).36 While it was long associated with Watteau’s name, it was never accepted by Watteau scholars as being by him. Starting in the 1960s, when it came on the market, it was reattributed to Mercier. However, it was not listed by Ingamells and Raines.

|

|

| 23. Philippe Mercier, Fête galante, oil on canvas, 47 x 55 cm. Whereabouts unknown (formerly New York, Newhouse Galleries). | 24. Philippe Mercier, Fête galante, oil on canvas, 47 x 55 cm. Whereabouts unknown (formerly New York, Newhouse Galleries). |

Also part of this set are two pendants once with Newhouse Galleries in New York (figs. 23-24). They had once been owned by Jules Strauss of Paris. As should be evident, the two pictures are closely related in style and composition to the ex-Segoura painting.37 According to Raines, the pair of pendants was attributed to Mercier in the early nineteenth century.38 Certainly they were given to Mercier in the 1920s when they belonged to Strauss, and when they were sold in the 1950s they still were under that attribution. Raines at first not only accepted the attribution to Mercier but posited that the pendants were very early works, painted while the artist was still in Germany. In the last half century these pictures dropped from the limelight and were rarely mentioned, much less included in his oeuvre, not even by Ingamells and Raines.39

|

| 25. Philippe Mercier, Fête galante, oil on canvas, 43.5 x 54.5 cm. Valenciennes, Musée des Beaux-Arts. |

The final painting to be considered in this group is a fête galante in the Musée des Beaux-Arts of Valenciennes (fig. 25). Perhaps already in the eighteenth century, but certainly by the early nineteenth, it was attributed to Watteau. It was listed under his name in the museum’s 1825 catalogue, and was still given to him in the 1898 catalogue. Louis Gonse was perhaps the first scholar to openly oppose the attribution to Watteau, writing in 1900 that it was “une oeuvre apocryphe.”40 Yet, more than a decade later, Edmond Pilon still accepted the picture as an authentic work of Watteau’s, praising its “si chaude coloration.”41 In the 1930s Alvin-Beaumont insisted on the attribution to Watteau.42 Yet perhaps no one else in the last eighty years has sought to claim this painting for Watteau.43 The museum now rightly classifies it under Mercier’s name, yet it does not appear in the Mercier literature.44

|

|

|

|

| 26. Philippe Mercier, Le Danseur aux castagnettes (detail). Whereabouts unknown (formerly New York, Wimpfheimer collection). | 27. Philippe Mercier, Fête galante (detail). Whereabouts unknown (formerly Paris, Galerie Segoura). | 28. Philippe Mercier, Fête galante, (detail). Whereabouts unknown (formerly New York, Newhouse Galleries). | 29. Philippe Mercier, Fête galante (detail). Valenciennes, Musée des Beaux-Arts. |

These five paintings—from the Wimpfheimer collection, Segoura, Newhouse, and Valenciennes—manifest a remarkable homogeneity of style (figs. 26-29). They are recognizably by one hand and from one moment in time. The stocky proportions of the figures, including the large heads, and the facial features, especially the rounded eyes and arched eyebrows, remain constants throughout. Unlike, say, the three paintings that we would remove from Mercier’s oeuvre—the ex-Pembroke, ex-Mainwaring, and ex-Northumberland pictures—that have nothing in common with each other stylistically, here there is a cohesiveness, so much so that the figures from one painting could easily be confused with those in another. Most important, this family resemblance carries over to the figures in Mercier’s L’Heureuse rencontre and the Courting Couple (figs. 16, 19). To my mind, there remains no doubt that all these works are by Mercier. If there is a difference between the set of five paintings and L’Heureuse rencontre and Courting Couple, it is that the latter two examples are more sophisticated and suave. The figures are more elegant in form and movement. This change records the apparent development in the artist’s style.

As will be seen, one of the most significant aspects of the five paintings that have been brought together here is that they are all closely based on Watteau’s paintings and drawings. They depend on inventions by Watteau that he created c. 1715. This remarkable unity of borrowings not only reinforces our attribution of these compositions to a single artist, Mercier, but it suggests something of where and how he and Watteau first met.

|

|

| 30. Comte de Caylus after Watteau, Scene with a man dancing, etching. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale. | 31. Anotine Watteau, Le Bal champêtre, oil on canvas, 96 x 128 cm. Paris, private collection. |

The general scheme of Le Danseur aux catagnettes, featuring an unpartnered dancer with castanets at the center, can be compared with a lost Watteau drawing etched by the comte de Caylus (fig. 30). The general idea of the composition was also used by Watteau for several paintings, including Le Bal champêtre and La Musette (fig. 31).

|

||

| 32. Mercier, Le Danseur aux castagnettes (detail). Whereabouts unknown (formerly New York, Wimpfheimer collection). | 33. Watteau, Le Bal champêtre (detail). Paris, private collection. | 34. Watteau, Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire (detail). Potsdam, Stiftung Preussische Schlösser und Gärten, Schloss Sans-Souci. |

Certain figures in Mercier’s Danseur aux castagnettes resonate with particular ones in Watteau’s works. This is especially true of the five figures at the far left of Mercier’s picture (fig. 32). His seated bagpipe player is almost identical to the musician in Watteau’s Le Bal champêtre (fig. 33).45 The woman resting the weight of her body on the thigh of her male companion is not only like the inclined woman in the lost Watteau drawing etched by Caylus, but this very same couple appears at the far left of Watteau’s Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire, now in Potsdam (fig. 34). Moreover, the adjacent couple in Mercier’s painting—a man looking over the shoulder of his seated female companion—echoes a similarly posed group in the Potsdam picture. In short, although Mercier captioned his etching, “Watteau pinxit,” suggesting that he was trying to palm his painting off as a genuine Watteau, he perhaps should have declared “Watteau inspiravit.” Whether Mercier was pastiching elements from these different sources or from a single, otherwise unrecorded Watteau composition, it is clear that in this instance he was very much dependent on his master’s ideas.

|

|

|

| 35. Philippe Mercier, Fête galante (detail). Whereabouts unknown (formerly Paris, Galerie Segoura). | 36. Antoine Watteau, Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire (detail). Potsdam, Schloss Sans-Souci. | 37. Antoine Watteau, Le Bal champêtre (detail). Paris, private collection. |

The Mercier fête galante once with Maurice Segoura is equally dependent on Watteau’s inspiration (fig. 35). Near the center of the painting, a Mezzetin and his lady companion stop in their promenade. They correspond in pose and costume to a pair in the foreground of Watteau’s Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire, although the woman’s skirt in Mercier’s painting falls at a different angle (fig. 36). Watteau painted a dog behind this couple but in his version Mercier awkwardly hid the front half of the dog behind the woman’s skirt. The couple standing to the right in Mercier’s painting corresponds to a couple at the far right of Watteau’s Le Bal champêtre (fig. 37).

|

|

| 38. Philipe Mercier, Fête galante (detail). Formerly Paris, Galerie Segoura. | 39. Antoine Watteau, Sheet of studies (detail), sanguine. Dijon, Musée des Beaux-Arts. |

Similarly, some of the characters at the left side of the ex-Segoura fête galante (fig. 38) can be related to early inventions by Watteau. For example, the woman seated in profile, one hand drooping limply in her lap and the other hanging equally limp at her side, assumes a distinctive pose. A similarly posed figure appears in reverse in a Watteau drawing now in the Dijon Musée des Beaux-Arts (fig. 39).46 Here, as elsewhere in the ex-Segoura painting, Mercier could have declared, “Watteau inspiravit.” But whether Mercier was inspired by this specific drawing or by a Watteau painting which contained the woman is, at least for present, moot.47

|

|

| 40. Philippe Mercier, Fête galante (detail). Formerly New York, Newhouse Galleries. | 41. Antoine Watteau, Compositional study, sanguine counterproof, 16.7 x 21.2 cm. Stockholm, Nationalmuseum. |

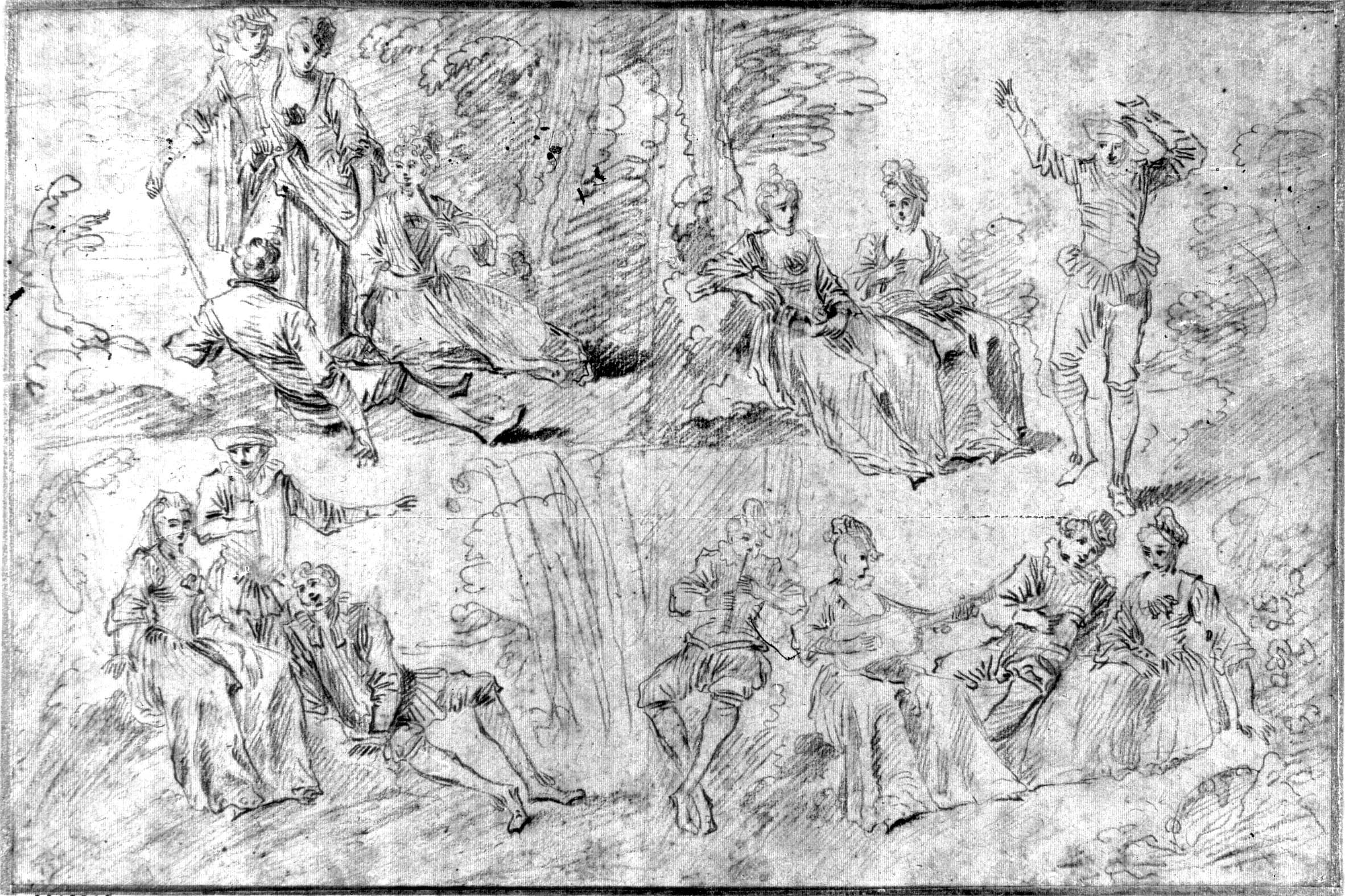

In the first of the ex-Newhouse pendants (fig. 40), the left side features a seated Mezzetin, a woman at Pierrot’s feet, a Mezzetin seated on the bench next to the clown, and a man and woman standing behind the group. These same five figures, posed the very same way, were together in a now lost Watteau drawing. That drawing is recorded in a counterproof that Count Nicodemus Tessin of Sweden bought in 1715 from Watteau and today is in the Stockholm Nationalmuseum (fig. 41).48

|

|

|

| 42. Philippe Mercier, Fête galante (detail). Formerly New York, Newhouse Galleries. | 43. Antoine Watteau, Compositional study, sanguine counterproof, 16.3 x 21.7 cm. Stockholm, Nationalmuseum. | 44. Charles Nicolas Cochin (after Watteau), Belles, n’écoutez rien, engraving. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale. |

At the right side of Mercier’s painting, a seated Harlequin gestures excitedly toward a woman who protectively covers her breast (fig. 42). A comparable (but by no means identical) group is seen in reverse in another Watteau counterproof from Tessin’s collection, also in the Stockholm Nationalmuseum (fig. 43). A similar group of a seated Harlequin menacing an actress is found in Watteau’s Belles, n’écoutez rien, a painting recorded in the Jullienne Oeuvre gravé (fig. 44). Lastly, the motif of Dr. Baloardo entering the scene at the far left in Mercier’s painting is similar in concept to the actor entering at the side of Watteau’s Pour garder l’honneur d’une belle, the pendant composition to Belles, n’écoutez rien.

|

|

| 45. Philippe Mercier, Fête galante (detail). Formerly New York, Newhouse Galleries. | 46. Antoine Watteau, Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire (detail). Potsdam, Schloss Sans-Souci. |

In the second of the ex-Newhouse pendants, a Pierrot bows toward a seated woman, his hat extended toward her, and they are surrounded by a full repertoire of other commedia dell’arte characters (fig. 45). A similar Pierrot bowing to a woman appears—but in reverse—among a crowd of figures at the center of Watteau’s Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire (fig. 46).

|

| 47. Antoine Watteau, Compositional study, sanguine, 18.5 x 30 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

Even more remarkable, the sense of the narrative and almost all the characters in Mercier’s painting, save for the four figures at the right, appear in an early Watteau drawing that is quite similar in style and spirit to the ones in Stockholm (fig. 47).49

| 48. Antoine Watteau, L’Enchanteur (detail). Troyes, Musée des Beaux-Arts. |

Moreover, three of the remaining characters at the right in Mercier’s painting—the two seated women and a standing Mezzetin—correspond to the actors at the side of Watteau’s L’Enchanteur (fig. 48). There are minor differences, as in the profile and frontal postures of the women’s heads, but otherwise the correspondences are remarkable.

Here again we need to ask whether Mercier combined elements from the French master’s drawings and paintings, or did Watteau himself use his studies to form otherwise unrecorded pictures that Mercier then copied? Whatever the answer, it is evident that in the two ex-Newhouse pictures Mercier was highly dependent on Watteau’s inventions.

|

|

| 49. Philippe Mercier, Fête galante (detail). Valenciennes, Musée des Beaux-Arts. | 50. Antoine Watteau assisted by Pierre Antoine Quillard, Assemblée pres d’une fontaine de Neptune (detail). Madrid, Museo del Prado. |

Lastly, there is the painting in the Valenciennes museum. The five central figures correspond to ones in the middleground of the Assemblée près d’une fontaine de Neptune in Madrid (figs. 49-50). Likewise, the two figures at the far left of Mercier’s composition correspond, albeit somewhat more freely, to ones in the right foreground of the Madrid canvas as well as to the figures in the Mercier painting formerly with Segoura (fig. 38). In short, the Valenciennes painting, like the others that we have discussed, shows that he was directly inspired by Watteau’s art.

Our recital of Mercier’s borrowings by might at first seem to reinforce the commonly held belief that he was an undiscriminating pasticheur and signifies a returned to the popularly held position discussed at the beginning of this inquiry. But, in fact, there are meaningful differences. Earlier, the paintings erroneously attributed to Mercier suggested that he relied on a variety of Watteau paintings as well as the Jullienne engravings, and that the great majority of the compositions that he borrowed from were familiar ones from Watteau’s later years. In contrast, the five Mercier paintings gathered here show that he relied upon a relatively limited number of early works by Watteau. There is no evidence whatsoever that he borrowed from Watteau’s later works or from the Jullienne engravings. Whether Mercier relied on a combination of Watteau’s early drawings and paintings, it is evident that all the works he borrowed from were relatively early ones. Despite the inability of scholars to agree upon a definitive chronology for Watteau’s oeuvre, Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire, L’Assemblée près d’une statue de Neptune, Le Bal champêtre, Belles, n’écoutez rien, and L’Enchanteur are generally dated somewhere between 1710 and 1715.50 Likewise, the drawings in Stockholm were bought by Tessin in 1715.

|

| 51. Pierre Antoine Quillard, Sheet of studies, sanguine, 20.7 x 32.1 cm. Chatsworth, Duke of Devonshire collection. |

This early date is reinforced by several Quillard drawings in Chatsworth, all of which come from an album of sketches after Watteau that the young Quillard apparently made while in Watteau’s studio in the years around 1715.51 On one sheet (fig. 51), Quillard drew in the upper right corner a vignette that is comparable to Mercier’s Danseur aux castagnettes and is also closely related to the lost Watteau drawing etched by the comte de Calyus (figs. 20, 30). On the same page, in the upper left quadrant, Quillard drew a composition closely related to the group in Watteau’s Assemblée près d’une fontaine de Neptune—the very figures that Quillard executed while working as Watteau’s pupil—and that Mercier employed in the Valenciennes painting (figs. 49-50). Similarly, Quillard’s little tableau in the lower left corner of the page resembles the group at the far left of the Valenciennes painting (fig. 25). The other Quillard sheets at Chatsworth contain transcriptions and modifications of other Watteau inventions, many of which resemble the repertoire of figures seen in Mercier’s early paintings.

We can conclude that Mercier knew Watteau early on in his career, well before the Parisian artist came to London in 1719. The idea that the two men first met in Paris was postulated almost a century ago by Dacier and Vuaflart but it has been overlooked by critics.52 Given the intimate knowledge of Watteau’s work that Mercier must have had, should we not presume that there was a personal relationship between the two men, and that Mercier worked within or had access to Watteau’s atelier? In turn, the evidence presented here sheds new light on the young Watteau. In light of Mercier’s and Quillard’s borrowings, should we not conclude that Watteau was not the isolated artist that later, romanticizing scholars have projected? Indeed, when we consider Watteau in relation to the various masters for whom he worked—Claude Audran, Philippe Meusnier, Antoine Dieu, etc—and the so-called “satellites” who emerged from his studio—Jean Baptiste Pater, Antoine Quillard, Nicolas Lancret, and of course, Mercier—must we not reassess the traditional image of Watteau?

During the time of Watteau’s stay in London in 1719-20 and in the years after Watteau’s death in 1721, Mercier continued to have contact with Watteau’s art, selling some of his master’s pictures, copying some of his paintings, and making prints after others. But these all postdate that initial meeting, an event that had great importance for shaping Mercier’s career.

NOTES

1. An abridged version of this study was presented to ArtWatch UK in London on September 30, 2013. I am grateful to this organization, especially Michael Daley and Selby Whittingham, for the opportunity and their encouragement.

2. Robert Rey, Quelques satellites de Watteau (Paris: 1931),58-98; equally pertinent is Émile Dacier, Albert Vuaflart, and Jacques Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs de Watteau au XVIIIe siècle, 4 vols. (Paris: 1921-29), esp. 1: 90, 100-03, 166; 3: 127-29, cat. 303-09. See also Robert Raines, “Philip Mercier, A Little-known Eighteenth-century Painter,” Proceedings of the Huguenot Society of London, 21 (1967), 124-37; Paul Wescher, “Philippe Mercier and the French Artists in London,” Art Quarterly, 14 (Autumn 1951), 179-94.

3. John Ingamells and Robert Raines, “A Catalogue of the Paintings, Drawings and Etchings of Philip Mercier,” Walpole Society Journal, 46 (1976-78), 1-70; idem, Philip Mercier 1689-1760, an Exhibition of Paintings and Engravings, exh. cat. (York City Art Gallery and Kenwood, Iveagh Bequest: 1969).

4. Martin Eidelberg, “Philippe Mercier as a Draftsman,” Master Drawings, 44 (Winter 2006), 411-49.

5. For the date of Mercier’s arrival in England and the portrait of the prince that he brought, see Ingamells and Raines, “A Catalogue of …Mercier,” 8 note 2 and 20, cat. 32. The date in Vertue’s text had previously been mistranscribed as 1711, thus confusing the issue.

6. Among those who deny that Mercier was Watteau’s host in London are Ellis K. Waterhouse, Painting in Britain, 1530 to 1790, 1953 (New Haven and London: 1994), 188. Rey, Quelques satellites de Watteau, 62-63, thought it possible that Watteau lived with Mercier when he visited London in 1719. Ingamells and Raines, Philip Mercier 1689-1769, 10, 15, also looked favorably on the idea that Mercier served as Watteau’s host.

7. For Mercier’s auction, see Eidelberg, "Watteau Paintings in England in the Early Eighteenth Century," The Burlington Magazine, 117 (September 1975), 577-78, where I surmised that the sale took place in 1724. The catalogue specifies only “Tuesday next, the 21st of this Instant April” and specifies that Mercier’s house was at St Martin’s Street, Leicester Fields. After 1724, April 21 did not fall on a Tuesday until 1730 but Mercier had already left Leicester Square by 1730; see Ingamells and Raines, “A Catalogue . . . of Mercier,” 8 note 4. My surmise that the sale took place in 1724 is proven correct by an announcement of the auction in The Daily Post, April 17, 1724, p. 1796.

8. A number of otherwise unrecorded English sale catalogues of the first half of the eighteenth century were transcribed by Richard Houlditch, Jr., in a two-volume manuscript: Sale Catalogues of the Principal Collections of Pictures Sold by Auction in England within the Years 1711-1759, 2 vols. (London: c. 1760). London, Victoria and Albert Museum, National Art Library, Ms. 867, 8-1938.

9. Ingamells and Raines, “A Catalogue of . . . Mercier,” 59-60, cat. 253.

10. Carlo Gambarini, A Description of the Earl of Pembroke’s Pictures (London: 1731), 67: ”3.—Wateaux. With many Figures in different Parts of the Landskip, some Dancing, some Singing; he painted his Figures finely drest in Gowns, and was the first who gave them genteel Airs, and not Stiff, as many did in Flanders, though otherways theirs were well painted; such were call’d Conversation.”

11. Sidney, 16th Earl of Pembroke, A Catalogue of the Paintings and Drawings in the Collection at Wilton House, Salisbury, Wiltshire (London and New York: 1968), 70-71, cat. 186.

12. As cleverly noted by Robert Raines, “Watteaus and ‘Watteaus’ in England before 1760,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts, s. 6, 89 (Feb. 1977), 53, a telling detail is that one of the children in the Pembroke picture has a fur-trimmed hat as in the engraving, a detail not in the actual Watteau painting.

13. For the date of the engraving, see Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs de Watteau, 1: 3-4; 3: 37. If the Pembroke picture was executed after 1726, that precludes the possibility that it could be indentified with a painting ascribed to Watteau from Gambarini’s collection that was sold at a London auction on March 10-12, 1725, lot 151. Raines had proposed linking the Pembroke picture and the 1725 sale; see Raines, “Watteaus and ‘Watteaus’ in England before 1760,” 52-53; also Ingamells and Raines, “A Catalogue of … Mercier,” 59-60, cat. 253.

14. Frederick Antal, Hogarth and his Place in European Art (London: 1962), 35.

15. Raines, “Philip Mercier, A Little-known Eighteenth-century Painter,” 137.

16. Ingamell and Raines, Philip Mercier 1689-1760, 7.

17. Raines, “Watteaus and ‘Watteaus’ in England before 1760,” 52-53.

18. Nicole Parmantier, “The Friends of Watteau,” in Margaret Morgan Grasselli and Pierre Rosenberg, eds., Watteau 1684-1721, exh. cat. (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1984), 43.

19. Brian Allen, “Watteau and his Imitators in Mid-Eighteenth Century England,” in François Moureau and Margaret Morgan Grasselli, eds., Antoine Watteau (1684-1721): le peintre, son temps et sa légende (Paris and Geneva: 1987), 259-60.

20. For this branch of the family, see Reginald Mainwaring Finley, A Short History of the Mainwaring Family (London: 1890), 53-56.

21. It was in the collection of Edgar Mills of New York and then was sold in 1929. It figured in a sale, New York, Parke-Bernet, June 8, 1939, lot 124, as “Attributed to Jean Antoine Watteau.” This painting was classified in Hélène Adhémar and René Huyghe, Watteau, sa vie—son oeuvre (Paris: 1950), 238, cat. 311, among works by the “École de Watteau, douteux, incertains.” It apparently was still associated with Watteau’s name in the late 1980s when it was in the collection of Jane Wever and sold for the sizable sum of $46,750.

22. Sale, New York, Sotheby’s, Oct. 13, 1989, lot 86, as “Manner of Jean Antoine Watteau;” London, Sotheby’s, Nov. 13, 1991, lot 87, as “Philip Mercier;” London, Sotheby’s, April 13, 1994, lot 124, as “Philip Mercier.”

23. Interestingly, in the early eighteenth century Watteau’s painting was in London, in the collection of Dr. Richard Meade, and thus theoretically would have been convenient for an English artist to study and copy. The foolish suggestion made in the 1991 auction catalogue that the balustrade in the Oteley Park painting was based on the one in Watteau’s Île de Cythère, another Watteau painting that was in London at the time, is unnecessary.

24. Sale, London, Sotheby’s, March 26, 1952, lot 102; sale, Paris, Palais Galliera, June 7, 1974, lot 26.

25. Ingamells and Raines, “A Catalogue of Mercier,” 58, cat. 245.

26. For the histories of the engravings, see Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs de Watteau, 3: 70, cat. 139; 111-12, cat. 265.

27. To cite just a few examples of these faux Merciers in recent years: New York, Sotheby’s, May 21, 1998, lot 211; Paris, Hôtel Drouot, Dec. 10, 1999, lot 88; Paris, Hôtel Drouot, Nov. 23, 2001, lot 6; Vienna, Dorotheum, June 21, 2005, lot 360; Paris, Christie’s, June 26, 2008, lot 50; Milan, Finarte, Feb. 25, 2009, lot 265; Amsterdam, Sotheby’s, Apr. 7, 2009, lot 64; Paris, Hôtel Drouot, Dec. 18, 2009, lot 52; London, Bonham’s, Apr. 13, 2011, lot 229.

28. In a previous study on Bonaventure de Bar, I found only twelve extant paintings to be actually by him, a small number compared to the more than one hundred copies, pastiches, and anonymous works that have been assigned to him faute de mieux. See Martin Eidelberg, “Defining the Oeuvre of Bonaventure ” (Parts 1 and 2), http://watteauandhiscircle.org.

29. For Mercier’s etching, see Ingamells and Raines, “A Catalogue of . . . Mercier,” 65, cat. 286.

30. For the two drawings associated with L’Heureuse rencontre, see Eidelberg, “Philippe Mercier as a Draftsman,” Master Drawings, 44 (2006), 416-18.

31. Sale, London, Christie’s, June 22, 1979, lot 129; London, Christie’s, April 22, 1983, lot 72.

32. Letter from John Ingamells to the author, Feb. 8, 2002.

33. The provenance of the painting can be traced back to the nineteenth century when it probably was in the collection of Admiral Sir George Seymour and was hidden under an attribution to Watteau. It passed by descent to Princess Victor of Hohenlohe Langenburg and was sold from her collection before her death in 1912; see Valda Machell, “The Remainder of the Hertford and Wallace Collections,” Burlington Magazine, 92 (Aug. 1950), 171. It was bought by Schnell, passed to the dealer Wertheimer, and then was owned c. 1924 by René Gimpel. He sold it at the high price of $45,000 (appropriate for a Watteau painting) to S. Reading Berton, and it subsequently entered the Wimpfheimer collection.

34. For Mercier’s etching, see Dacier, Vuaflart and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs de Watteau, 3: 128, cat. 307; Ingamells and Raines, “A Catalogue of . . . Mercier,” 66-67, cat. 291.

35. For example, Adhémar and Huyghe, Watteau, sa vie—son oeuvre, 233-34, cat. 224; Giovanni Macchia and Ettore C. Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (Milan: 1968), 106, cat. 120.

36. The painting sold Paris, Hôtel Drouot, Nov. 14, 1967, lot 33, as “genre d’Antoine Watteau,” and was bought by Newhouse Galleries of New York; see its advertisement in The Magazine Antiques, 97 (May 1970), 663, where it was reattributed to Mercier. It subsequently entered the collection of Edmond de Rothschild, Paris, and in the spring of 1996 was bought by Maurice Segoura, still with the attribution to Mercier in place.

37. When the paintings were in the collection of Jules Strauss, one was exhibited in Le Théâtre à Paris XVIIe-XVIII siècles, exh. cat. (Paris: Musée Carnavalet, 1925), cat. 48, and was discussed and illustrated in Rey, Quelques satellites de Watteau, 76 and pl. XI. Rey confused the work with the Watteau composition Par la tendresse et les soins. The two Mercier pendants were advertised by Newhouse Galleries in Art Quarterly, 14 (1951), 267, but have not been seen since. Both were discussed by Eidelberg, Watteau’s Drawings: their Use and Significance, Ph. D. thesis, Princeton University, 1965, 216-26. Pierre Rosenberg and Louis-Antoine Prat, Antoine Watteau, catalogue raisonné des dessins, 3 vols. (Milan: 1996): I: 144, 174, 198, cat. 91, 110, 125, offer only a partial, slightly confused recounting of my thesis.

38. Raines, “Philip Mercier, A Little-known Eighteenth-century Painter,” 128-29.

39. The two pictures are not listed in Ingamells and Raines, “A Catalogue of . . . Mercier.” According to John Ingamells (letter to the author, Feb. 8, 2002), by the time the two authors compiled their 1978 catalogue raisonné they “came to feel uneasy about them.”

40. Louis Gonse, Les chefs-d’oeuvre des musées de France (Paris: 1900), 331.

41. Edmond Pilon, Watteau et son école (Paris: 1912), 5.

42. Victor Alvin-Beaumont, Autour de Watteau (Paris: 1932), 94.

43. The Valenciennes painting is not listed in Adhémar and Huyghe, Watteau, sa vie—son oeuvre, not under Watteau’s or Mercier’s name. Nor is it cited by Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau.

44. E.g., Trésors des musées du Nord de la France, exh. cat. (Dunkerque, Valenciennes, Lille: 1980), 176. The Valenciennes painting does not appear in Ingamells and Raines, “A Catalogue of . . . Mercier.”

45. Also related is the bagpipe player in Watteau’s L’Amour au théâtre français.

46. For the drawing, see Rosenberg and Prat, Antoine Watteau, catalogue raisonné des dessins, 1: 218-19, cat. 137.

47. As an aside, it should be noted that the right-hand portion of the ex-Segoura painting is closely related to a drawing that I have previously attributed to Mercier; see Eidelberg, “Philippe Mercier as a Draftsman,” 426-27. The drawing duplicates the entire right side of the ex-Segoura painting, not only all seven figures but even the headless dog. The drawing shows the very same drapery folds, facial features, and curious expressions present in the painting, so that each affirms the attribution of the other. It seems likely that the drawing was not made to plan the painting but rather was a copy after the picture in preparation for an etching.

48. Rosenberg and Prat, Antoine Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins, 1: 144-45, cat. 91. There is a striking relation between this counterproof and Les Jaloux, the painting that Watteau submitted to the Royal Academy in 1712.

49. Rosenberg and Prat, Antoine Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins, 1: 198-99, cat. 125.

50. Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire has been dated to c. 1710, which is perhaps a tad too early; L’Assemblée près d’une statue de Neptune has been placed at c. 1710-12; Le Bal champêtre has been dated to somewhere between 1712 and 1716; L’Enchanteur has been dated c. 1712-14; see, for example, Grasselli and Rosenberg, Watteau 1684-1721, 264-66, 289-95, 289-95, 283-84, respectively.

51. For the Chatsworth drawings, see Martin Eidelberg, “P.A. Quillard, an Assistant to Watteau,” Art Quarterly, 33 (1970), 53-54, 63-66. However, Margaret Morgan Grasselli, “Following in Watteau’s Line: Some Drawings by Jean-Baptiste Pater,” Master Drawings, 38 (2000), 161-65, has challenged the attribution to Quillard and instead proposed that they be assigned to Pater. My response to that unconvincing idea will appear in a future study on Watteau’s assistants.

52. This was suggested by Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs de Watteau, 1: 90, but was neglected by most later scholars. Rey, Quelques satellites de Watteau, opined that it was difficult to decide if Mercier had known Watteau in Paris and been influenced by him before [sic] 1715. In their chronology of Mercier’s life, Ingamells and Raines, Philip Mercier 1689-1760, 10, barely take into account Mercier’s stay in Paris and its implications. Marianne Roland Michel, “Watteau and England,” in Charles Hind, ed., The Rococo in England, A Symposium (London: 1986), allowed that Mercier arrived in 1716 from Paris, “where he might have known Watteau.”