JACQUES VIGOUREUX DUPLESSIS AND CHINOISERIE

© Martin Eidelberg

Created July 2023; revised August 2023

© Martin Eidelberg

Created July 2023; revised August 2023

Chinoiserie affected French eighteenth-century culture, not least the furnishings of aristocratic homes. Yet with the passage of time and changes in taste, little has survived, especially not from the first decades of the century. There are the great tapestry cycles woven at Beauvais, individual chairs with chinoiserie coverings, Chinese porcelains with French eighteenth-century bronze mounts, and lacquered screens and boxes in multiple sizes. But only rarely are we presented with whole ensembles. The few chinoiserie rooms that have survived intact, such as those now in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, and at Rosenburg Castle in Copenhagen, serve as rare, exceptional witnesses to what once was a dominant mode of interior decoration.

A major exponent of chinoiserie décor was Jacques Vigoureux Duplessis (c. 1680-1732), a relatively minor but not entirely unknown painter.1 Although he had an interest in traditional religious and genre subjects, he took particular delight in Chinese themes. They were his specialty. Setting aside the stage sets that he executed for the Paris Opera, he devoted much of his energy to the painting of small-scale objects. In her survey of exotic subjects in eighteenth-century art, Roland Michel dismissively passed over Vigoureux Duplessis’ subject matter, writing that “he is known only for his overdoors, fire-screens and folding screens, all featuring almost exclusively Chinese themes.”2 Yet his work as a creator of such useful objects should not be dismissed. That portion of his oeuvre throws new and important light on the development of chinoiserie in France in the early eighteenth century.

|

|

A convenient starting point for this study is the screen now in the Walters Art Museum (fig. 1).3 Signed and dated 1700, it is the earliest known work from Vigoureux Duplessis’ hand. Although its curious composition is striking, it proves to be a formula that the artist often employed. At the center is a painted tondo with the scene of Danae visited by Jupiter in the form of a shower of golden coins—a traditional European subject. But supporting the tondo are three Chinese men, though their costumes are not actually Chinese but fanciful French theatrical garb. Their short skirts and caps adorned with bells betray this French convention. Adding to the rich complexity of this work, there is the illusion of a carved relief with nude figures, a fringed curtain, and a single andiron. A century ago, this painting first came to light in the Parisian collection of Jules Strauss. He was closely allied with Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, and these scholars proposed that, given the artist’s association with the Paris Opera, the painting was a modello for a stage curtain.4

|

2. Jacques Vigoureux Duplessis, Fire Screen with a Scene of Diana and Her Nymphs Surprised by a Satyr, oil on canvas, 80 x 92.7 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

However, as I pointed out in my previous study of the Walters Art Museum’s painting, that idea is not viable: the Chinese actors and especially the andiron would not have made sense when enlarged to the scale of a theater curtain. Rather, Vigoureux-Duplessis’ painting functioned as a fire screen, that is, as a screen used in the summer months when there was no need for a fire and the fireplace opening needed to be closed off. Moreover, this would explain the presence of the andiron and, as well, the yellow fringed curtain—the type of curtain often used to cover fireplace openings. Since we proposed that the picture was a fire screen, the idea has taken root and has not been challenged.

In the half century since that publication, other fire screens by Vigoureux Duplessis have come to light. The closest in size and format is one that appeared at auction in 2001 (fig. 2).5 Its attribution to our artist, a most obvious conclusion, was based on the evident parallels with the Baltimore picture. Previously, when the painting was auctioned in the late nineteenth century, it had been attributed to Claude Gillot.6 The mistake is understandable, in light of the two painters’ common interest in the theater and their penchant for depicting excited movement. The format of this fire screen, like the one in Baltimore, depicts a shallow enclosed space, with just a hint of an arch in the upper corners. Here too the viewer looks down at the scene since the fireplace opening would be at floor level. The faces of the men struggling to hold the tondo are explicitly Asiatic, while the dancers at the sides, wearing equally fantastic theatrical costumes, have faces that seem more European.

|

3. Jacques Vigoureux Duplessis, Fire Screen with a Scene of the Chinese Imperial Court, oil on canvas, 73.5 x 81.5 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

A third fire screen appeared on the Paris market around 2000 (fig. 3).7 Again the scene is set in a restricted space defined by stone walls and a shallow arch at the top. Here, however, the back wall opens to a wide expanse of light blue sky. A relatively small oval with the portrait of a woman has replaced the large tondos that dominate the previous examples, though energetic Chinese performers still populate the foreground. The background contains an imaginative scene of life in the imperial court, with the rulers seated on a raised platform, flanked by a harem of women at the left, and men prostrating themselves at the right. Festoons of flowers are hung at top, a feature that frequently appears in the artist’s later paintings.

Another of Vigoureux Duplessis’s specialties were free-standing screens, most with Chinese subjects. A prime example is a pair of screens that were sold from the Victor Rothschild collection in 1937 (figs. 4, 5).8 They had been in the family since the nineteenth century. More recently, this pair of screens reappeared at auction in 1975.9 They feature motifs that became standard in such works: Chinese performers, medallions with mythological themes, imitation stone reliefs. Proud of his work, the artist signed both screens: “J. V. Duplessis Invenit et pinxit 1730.” The unusual format of the signature (“invenit et pinxit”) apes the one on the Baltimore fire screen. However, the date here is thirty years later. Although there may be small differences between his various works, his oeuvre shows a remarkable consistency.

Closely related are a pair of screens that were discovered a half century ago in the attic of the Lord Cavendish’s home at Holker Hall.10 Although no artist’s name was attached to them, the rightmost leaf is supposedly signed “J Vigoureux.” The scenes follow Duplessis’ formula of crowds of lively people in the lower register, columns providing a vertical accent, and circular medallions and floral garlands filling out the upper regions. Rather than containing the artist’s customary mythological themes, the rondels at the top present topographical views, painted in grisaille, and each site labeled: “L’Isle de S. Helena, Le Magazine de la Compagnie à Firando, La Ville Ownuary et son château, L’Isle de Pulo Tynien, La Ville de Osaoco, La Ville de Sesale, La Ville de Jedo, La Ville de Saccay.” A theory has evolved at Holker Hall that these locales commemorate stops made along the route by the first Siamese embassy to Paris. Yet one may well wonder if this itinerary corresponds to the embassy. The Japanese ports of Osaka and Yedo, for example, are not aligned with a Bangkok–Paris trajectory. In any event, these depictions were probably based on engravings of the sort that could be found in contemporary travel literature.

A large six-part screen in Marble House, one of Newport, Rhode Island’s ostentatious mansions, is a curious story of survival (figs. 6, 7).11 It remained intact for two hundred years, until the late nineteenth century when it was mounted in an elaborate gilt wood frame by the Parisian firm of Jules Allard et fils—a decorator’s attempt to rival the splendors of the palace at Versailles. Its painted surface appears to have been extensively retouched as part of the beautification process. It was bought by Mrs. William K. Vanderbilt, but its earlier history is not known.

The screen at Marble House closely follows the formula already witnessed in the previous examples: a milling crowd of Chinese figures below, tall columns supporting a confused architectural scheme above, garlands of flowers, and medallions with classical myths. As is evident, once the artist had established a basic concept, he could and did repeat it frequently

|

8. Jacques Vigoureux Duplessis, Three Leaves of a Six-Part Folding Screen, oil on canvas, 143 x 56 cm each leaf. Whereabouts unknown. |

Yet another of his screens with chinoiserie elements emerged on the auction market in 2022 (fig. 8).12 It has the familiar components of Duplessis’ screens: milling crowds below, slender columns festooned with floral garlands and portrait medallions, and framed quadri riportati with mythological subjects. The unrelated Ovidian narratives portray Perseus and Andromeda, Pan and Syrinx, Eurydice, Acis and Galatea, Pyramus and Thisbe, and Amphitrite. While the screens constitute Duplessis’ standard decorative vocabulary, the ensemble is richer and more dense than usual. Yet the artist’s authorship cannot be doubted, especially since one of the leaves is signed “Vigoureux Duplessis / invenit et pinxit.”

|

9. 10. Jacques Vigoureux Duplessis, The Siamese Ambassadors and The Persian Ambassador, oil on canvas, 160 x 140 cm each. Fontaine-Chaalis, Abbaye royale de Chaalis. |

Overdoors were another area in which Duplessis displayed his talents as a painter, as is witnessed by a pair of overdoors in the Abbaye at Chaalis (figs. 9, 10).13 One depicts the mission of the Siamese ambassadors to the court of Louis XIV in 1686, and the other shows the Persian ambassadors in 1715. As the two pictures were painted as a pair, they must have been executed after the latter event, that is, after 1715.

|

|

11. The Chief Siamese Ambassador, Ok-Phra Visut Sunthorn, engraving. |

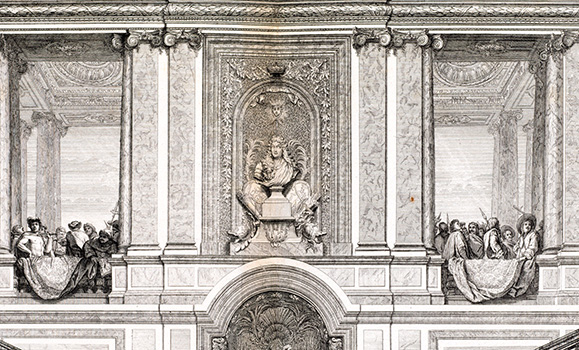

12. Louis Surugue, Staircase of the Ambassadors in the Palace at Versailles (detail), engraving. |

One of the striking aspects of these overdoors is that they present accurate depictions of the men portrayed, and were probably based on the engraved portraits that were then widely circulated (fig. 11). Meant to be seen di sotto in su, these august figures stand behind richly massed textiles, very much in the manner of the Staircase of the Ambassadors in the palace at Versailles, where courtiers look down upon the ambassadors and noble visitors who ascend to pay homage to the king (fig. 12). While Vigoureux Duplessis’ overdoors could have embellished a large house, it is also possible that they were intended for a more public space such as a Jesuit association involved in missionary work, or a mercantile establishment involved in the newly opened trade between France and the Near and Far East. We can only speculate about their original placement and their possible role in an even grander scheme of paintings.

|

13. Jacques Vigoureux Duplessis, A Chinese Imperial Official, oil on canvas, 95.5 x 73.7 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

An exceptional addition to the painter’s oeuvre is a previously unknown “portrait” of a member of the Chinese court (fig. 13). It appeared at auction in Paris in 2003 with no prior history.14 Is the sitter Chinese or European—that is the question. Is it an actual portrait or is it a fancy piece with an extravagant Oriental costume as the real subject? The many dragons, peacocks, and ostrich plume dominate this large, impressive picture, yet the servant pulling back the curtain at the right vies for attention and adds, perhaps, a slightly comic effect.

|

14. Jacques Vigoureux Duplessis, Allegory of Winter(?), pen and brown ink with wash, 14.9 x 17.3 cm. New York, Robert Simon Fine Art. |

Although the pictures at Chaalis are the only two extant overdoors from Vigoureux Duplessis’ hand, there are indications that he painted others. One such indication is a drawing that appeared at auction in New York in 1986 with an attribution to Claude Gillot (fig.14).15 Both its boldly Baroque use of wash and its Chinese theme suggest that Vigoureux Duplessis was its true author. Stylistically the sheet corresponds to other drawings attributed to him, all consonant with the range of subjects with which he is associated.16 Its compact triangular composition and implied point of view from below suggest that it would have been well suited for an overdoor.

What is the subject of this design? At the bottom are two Chinese men, evidently cold, warming themselves at a fire. At top, a nude, bearded god sends down streams of wind. Perhaps this is an allegory of Winter, one that combines Classical and Chinese elements—an unusual amalgam that typifies Vigoureux Duplessis’ work. If an allegory of Winter, then three more such designs must have completed the cycle of the year.

|

15. Jacques Vigoureux Duplessis, Chinese Children on Clouds, black chalk, pen and brown ink with wash, 25 x 31.3 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

A drawing that appeared on the Paris auction market in 2006, rightly attributed to our artist, shows Chinese children seated on puffy clouds (fig. 15).17 Its medium of pen and ink with bold, vivacious washes is quite similar to that of the previously discussed drawing. It too is composed with an implicit viewpoint from below, and this is emphasized by the clouds on which the children sit. The lightly drawn framing lines indicate that the composition was meant for a painting to be inset onto a wall, within the graceful curving lines of a rococo boiserie.

Lastly, we might consider a number of other paintings by our artist, all with chinoiserie subjects, which may have been simple, stand-alone paintings or may have been intended as parts of larger decorative ensembles.

|

|

16. Jacques Vigoureux Duplessis, The Emperor and Empress of China at a Harbor, 38.7 x 47.6 cm Whereabouts unknown. |

17. Beauvais Workshop, The Empress of China Sailing (detail), tapestry. |

Within this group is a curious picture of the Emperor and Empress of China at a Harbor (fig. 16).18 The emperor gesticulates with one hand, but is he simply pointing to his ship or is he inviting the empress to embark on a sea voyage? In certain limited ways this composition recalls elements in the Beauvais tapestry cycle, the Première tenture chinoise (fig. 17). But was Duplessis’ painting, like the Beauvais tapestry, part of a fuller cycle of images and a running narrative? Regrettably, nothing of the painting’s prior history and original context is known.

|

18. Jacques Vigoureux Duplessis, Scaramouche as a Chinese Woman, oil on canvas, 72 x 91 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

One of the most surprising and least expected of Duplessis’ compositions is one that shows a commedia dell’arte character—probably Scaramouche, to judge by his drooping moustache—swathed in female attire (fig. 18).19 In his left hand he holds a cut stalk of sugar cane. At the left, a woman pulls back a curtain and is surprised to find this Chinese “lady.” While the exact narrative remains unclear, its comic intent is evident.

|

19. Jacques Vigoureux Duplessis, A Scene of Religious Observance, measurements unknown. Whereabouts unknown. |

The last painting to be considered here and equally atypical of Vigoureux Duplessis’ works is executed in partial grisaille (fig. 19). It shows two women standing next to an altar, a prostrate worshipper, and a small man with bagpipes. All of this is set against a veined red marble stone. Was this simply a framed painting or was it used illusionistically as part of a stone frieze? Were there other such paintings that together formed a decorative ensemble? Those important questions require additional evidence before they can be answered.

CONCLUSION

Vigoureux Duplessis’ importance lies in the fact that his work marks an opening phase of French early eighteenth-century chinoiserie, a position that is generally overlooked. He and his work were not mentioned in Hélène Belevitch-Stankevich’s ground-breaking publication of 1910, Le Goût chinois en France au temps de Louis XIV, and he was still ignored in Yohan Rimaud’s recent exhibition in Besançon, Une des provinces du rococo; La Chine rêvée de François Boucher. Yet Vigoureux Duplessis was a leader in the field. His work coincided with Claude Audran’s exploration of the theme in the world of arabesques, and predated Watteau’s chinoiseries at La Muette. As demonstrated by the many chinoiserie paintings presented here, there evidently were many ensembles in France which manifested an interest in the Far East in the early eighteenth century, and Jacques Vigoureux Duplessis played a significant role in fostering this taste.

NOTES

1 I am indebted to my colleagues Kee Il Choi and David Pullins, Associate Curator of European Paintings, Metropolitan Museum of Art, for their good advice and counsel.

2 Marianne Roland Michel, in Colin Bailey, Philip Conisbee, and Thomas W. Gaehtgens, The Age of Watteau, Chardin and Fragonard (New Haven, London, and Ottawa, 2003), 115.

3 See Martin Eidelberg, “A Chinoiserie by Jacques Vigouroux Duplessis,” Journal of the Walters Art Gallery, 35 (1977), 62-76.

4 Emile Dacier, Albert Vuaflart, and Jacques Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs de Watteau, 4 vols. (Paris: 1921-29), 1: 7. Sale, Paris, Galerie Charpentier, May 27, 1949, lot 40. It was titled “Danaé” and described as being inspired by eighteenth-century opera.

5 New York, sale, Sotheby’s, May 23, 2001, lot 42, sold for $81, 250. The painting appeared at auction three years later: New York, Sotheby’s, May 27, 2004, lot 50, bought in.

6 Paris, sale, April 25, 1883, Beurdeley collection, lot 329, as by Claude Gillot.

7 In 1939, when this fire screen was with the Galerie Cailleux of Paris, it was misattributed to Guy Louis Vernansal and Christophe Huet. It subsequently passed into the collection of baron and baronne Gourgaud. By 2002, well after the Baltimore painting had been published, these screens were reattributed to Vigoureux Duplessis.

8 Sale, London, Sotheby’s, April 19-22, 1937, Victor Rothschild collection, lot 2. According to the firm’s official list, the screens were sold to the dealer Jacques Helft.

9 Sale, Paris, Palais Galliera, November 27, 1975, lot 80.

10 I thank Hugh, Lord Cavendish, for his assistance.

11 I am grateful to Nicole Williams and Victoria McKenna of the Preservation Society of Newport County for their help.

12 Paris, Sotheby’s, October 13, 2022, lot 594, 143 x 133.5 cm (overall width).

13 Paris, sale, Christie’s, June 15, 2023, lot 15.

14 For these paintings, see New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Visitors to Versailles: from Louis XIV to the French Revolution, ed. Daniëlle Kisluk-Grosheide and Bertrand Rondot (New York: 2018), cat. 62, 72.

15 New York, Sotheby’s, January 16, 1986, lot 98.

16 See, for example, an ink drawing in the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, inv. 1931-73-233; also the drawings sold in Paris, Christie’s, March 21, 2002, lot 169, and March 23, 2005.

17 Paris, Christie’s, March 23, 2006, lot 119, bought in.

18 New York, Christie’s, October 7, 1993, lot 94. According to the firm’s price list, the picture sold for $16,100.

19 Paris, Hôtel Drouot Montaigne, June 29, 1989, lot 34.