Philippe Mercier and the Miles Master

© Martin Eidelberg

Created November 12, 2013; revised July 2020

Click to Print or Download PDF Version

|

|

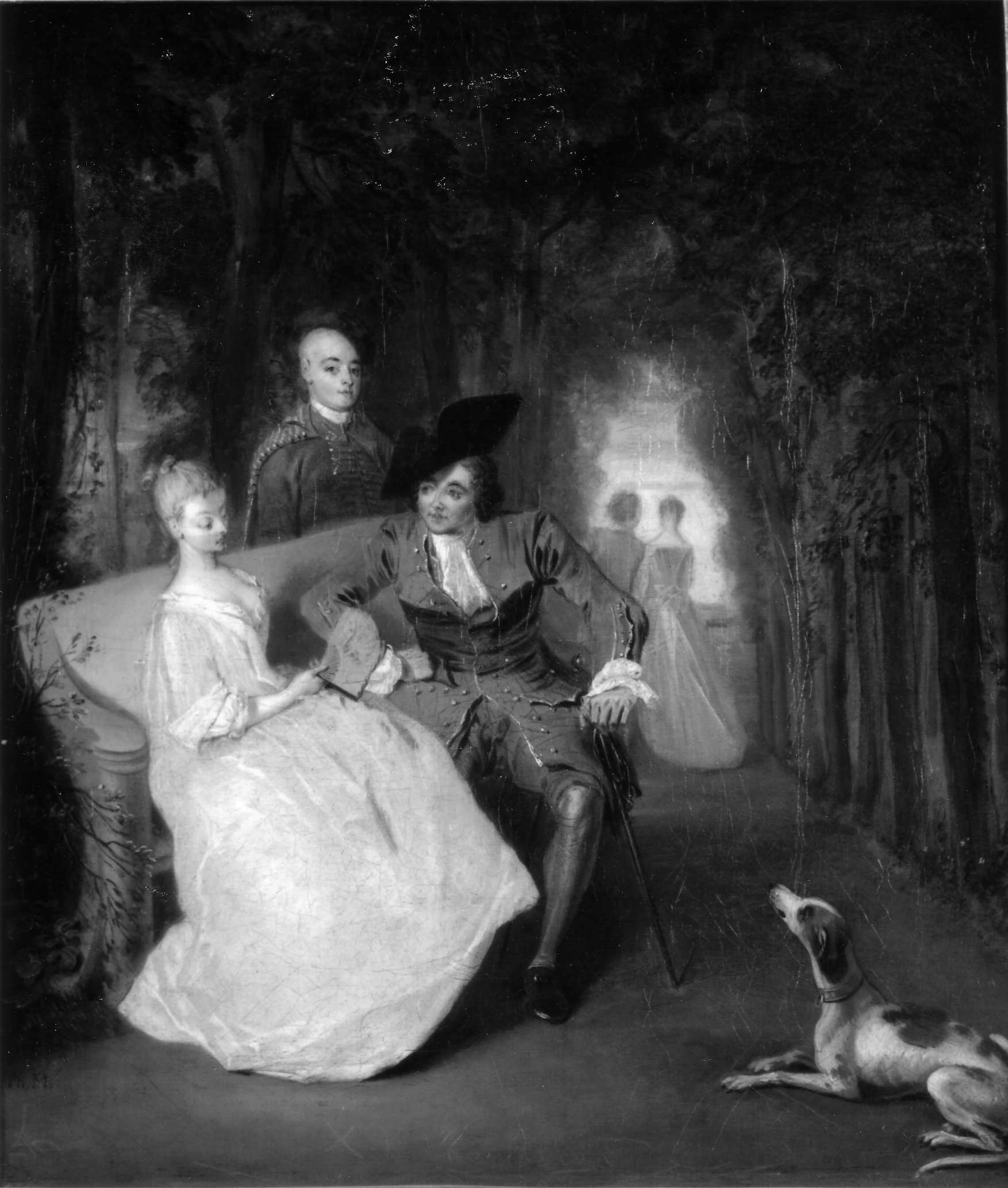

| 1. The Miles Master, Fête galante, oil on canvas, 99.1 x 156.1 cm. Whereabouts unknown (formerly London, Roy Miles collection). | 2. Detail of figure 1. |

A key element in Roy Ingamells and Robert Raines’ construction of Philippe Mercier’s early career as a painter is a fête galante then in the collection of the celebrated London dealer Roy Miles (figs. 1-2).1 It depicts elegantly dressed men and women dancing on the terrace of a garden, a trio of musicians at the left, and others at each side conversing. Completing the repertoire of characters, a man dressed as Pierrot appears at the right. This work was apparently unrecorded until it appeared at a London auction in 1973.2 These men were undoubtedly attracted to the picture not only by its appearance but also by its signature: “Mercier Pinxit 17….” Although there now is good reason to doubt the signature’s authenticity, at the time it evidently seemed convincing.

|

| 3. Philippe Mercier, Fête galante, oil on canvas, 47 x 55 cm. Whereabouts unknown (formerly New York, Newhouse Galleries). |

Ingamells and Raines not only published this painting in their catalogue raisonné of Mercier’s works, but they used it to postulate his artistic beginnings in Germany.3 They proposed that this canvas represented Mercier’s earliest, otherwise unknown manner. It would have been executed while he was still in Berlin and before he went to England in 1716. Previously Raines had argued that a pair of fêtes galantes belonging to the Newhouse Galleries of New York (fig. 3) represented that early phase of Mercier’s activity but then Ingamells and Raines abandoned the Newhouse paintings altogether, dropping them from their catalogue raisonné of Mercier’s oeuvre.4

|

| 4. Philippe Mercier, Courting Couple, oil on canvas, 34.9 x 29.8 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

However, Roy Miles’ picture bears no stylistic relationship to German painting in the early 1710s. In fact, it presupposes the creation of the fête galante in Paris after 1715/20 and, as will be seen, Miles’ painting probably dates from the 1720s or perhaps even later, from the 1730s. Most damning of all, the style of the painting bears no resemblance to Mercier’s earliest manner nor does it correspond to Mercier’s slightly later works of the mid 1720s (fig. 4). The distinctive, perhaps even unpleasant figures in the Miles painting, the exaggerated, lunging movements of the men and women, and their curiously warped faces¾all these elements set the picture apart from Mercier’s known oeuvre.

Equally compelling is the fact that at least seven additional works can be attributed to this same artist. In the past, these pictures have been loosely but unconvincingly associated with other masters, ranging from Watteau to Lancret, Pater, and Mercier. Significantly, none of these other paintings are signed or have been documented to be by these or any other specific artist. Yet, as will be seen, one man was responsible for all of them. To give appropriate coherence to this otherwise unidentified painter’s oeuvre, I have chosen to name him, faute de mieux, “The Miles Master.”

| 5. The Miles Master, Fête galante, oil on canvas, 79 x 95 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

A fête galante that was in a Dutch collection in the 1960s or early 1970s reveals all the distinctive characteristics of the Miles Master (fig. 5). The exaggerated movements and the way in which the bodies are inclined are persistent elements in his work. The male dancer at the center may recall certain figures in Lancret’s paintings, but the male dancer at the left is far more extreme in his exaggerated movements. Likewise, if a plumb line were extended down from the female dancer, both her legs would be to the left of it. This anonymous painting apparently was consigned to the limbo of “school of Watteau” when it was in the Netherlands, but when it appeared at auction in New York in 1979, just six years after the appearance of Roy Miles’ painting, it was—perhaps not coincidentally—given to the School of Mercier.5 If the resemblance to the Miles painting had been noticed, that is laudable. But, as I would suggest, neither painting should be assigned to Mercier.

|

| 6. The Miles Master, Fête galante, oil on canvas, 56.5 x 83 cm. Mâcon, Musée des Ursulines. |

A version of the previous picture was recently discovered in the Musée des Ursulines in Mâcon (fig. 6).6 It repeats the central section of the previous composition, but not the figures at the left nor the children next to the hurdy-gurdy player. Also the statue at the right has been cropped away and the expanse of trees and sky at the top of the painting has been eliminated. One might almost think that the painting has been cut drastically, but the absence of the children next to the hurdy-gurdy player suggest that the Mâcon painting was intended as a reduced repetition.

| 7. The Miles Master, A Game of Blind Man’s Bluff, oil on canvas, 34 x 43 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

Another painting assignable to our Notname is a fête galante that appeared at auction in Brussels in 1968 with an improbable attribution to Watteau himself (fig. 7).7 Like the painting owned by Roy Miles, this composition features a central grouping of figures, a small wedge of additional figures in darker tones at the left to create a repoussoir, and an opening to the distance at the right that creates a sense of depth. Almost all of the characters lean to one side or the other to simulate movement but they seem hyperactive rather than graceful. The high garden wall curves out dramatically, like the one in the Miles painting, to create another flaring accent in this already busy composition.

| 8. The Miles Master, Fête galante, oil on canvas, 45 x 53 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

A fourth picture by the Miles Master was sold in a Cologne auction in 1978, this time given to the circle of Lancret (fig. 8).8 Here again, the principal dancer leans to the left while Harlequin leans to the right. The child at the left also has a distinctive, unexplained cant, but most bizarre of all is the man at the far right who steps out from behind shrubbery on rubbery legs that seem disassociated from his body.

| 9. The Miles Master, Fête galante, oil on canvas, 40.6 x 51.5 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

Yet another painting wrongly attributed to Lancret but assignable to the Miles Master was on the New York market in the 1970s (fig. 9).9 The inclined stance of the female dancer seems par for the course, but the posture of her male partner is even more remarkable: his legs are not aligned with the angle of his torso. The bland face of the woman and the curiously warped faces of the two women at the right are recurring characteristics in the work of the Miles Master.

|

| 10. Miles Master, Fête Galante with a Woman Dancing, oil on canvas, 69 x 83 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

A fête galante coming out of Germany and assignable to the Miles Master features a single woman dancing, with other figures in attendance, some with musical instruments, others exchanging words of love (fig. 10).10 Although attributed to Watteau’s workshop, a meaningless phrase for an artist who did not have a workshop, this painting is far removed from Watteau and Paris. The intensity of her dance step, for example, is not at all like French pictures. The steep inclination of her body is also disturbing; if a plumb line were dropped from her head, three-quarters of her body would be off center. The woman’s hardened facial features and the way that she holds her generous skirting is very much like other scenes we have considered by the Miles Master (for example, fig. 9). Not least, the idea of showing a female dancer without a male companion is an unusual occurrence except, say, for portraits of the ballerina La Camargo.

| 11. The Miles Master, Fête galante, oil on canvas, 65 x 81 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

A scene with music-making that came onto the French market in 1964 has all the by-now familiar syndromes (fig. 11).11 The exaggerated, doll-like proportion of the characters, the awkward positions of limbs, and the dull, expressionless faces betray the Miles Master. Although the painting was attributed to Pater when it was offered at auction, it obviously has nothing to do with him.

|

|

| 12. The Miles Master, Fête galante with Masked Figures, oil on canvas, 64 x 80 cm. Whereabouts unknown. | 13. The Miles Master, Scene galante, oil on canvas, 40 x 50 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

Our last two additions to the Miles Master’s oeuvre were presented simply as anonymous eighteenth-century pictures when they came up for sale. One is a painting that twice was on the Vienna market, each time attributed simply to a French master of the eighteenth century (fig.12).12 Although the composition is quite similar to the preceding ones, the subject is slightly different in that a number of the characters are fancily costumed—as a Turk, a Punchinello, and men as knights or martial gods in suits of armor. But if the subject is slightly unusual, the people’s faces and lurching, inclined poses are unmistakable. The last picture, a composition with just three primary figures was on the Brussels market where it was presented as an anonymous work of the eighteenth century (fig.13).13 It too should be given to the Miles Master.

|

|

| 14. Jean Baptiste Pater, The Dance, oil on canvas, 56.7 x 45.7 cm. London, The Wallace Collection. | 15. Nicolas Lancret, A Game of Blind Man’s Bluff, oil on canvas, 97.3 x 129.1 cm. Potsdam, Stiftung Preussische Schlösser und Gärten, Schloss Sans-Souci. |

These eight paintings share a unity of approach and execution. They reveal the general influence of French rococo painting, not so much from Watteau as from Pater, Lancret, and that generation of Watteau’s so-called satellites. The Miles Master’s awkward poses reflect the animated gestures frequently encountered in the works of Pater and Lancret, but whereas in a typical Pater such as The Dance in The Wallace Collection (fig. 14), the figures move gracefully and convincingly, comparable gestures in the Miles Master’s works are exaggerated and awkward. The Miles Master’s preference for tall, curving garden walls, often adorned with urns set on high, has much in common with Lancret’s compositions, such as his Blind Man’s Bluff in Potsdam (fig. 15). And Lancret’s centrifugal depiction of that game seems to anticipate the formula attempted by the Miles Master (fig. 7). In short, the features seen in these fêtes galantes invalidate the possibility of the early 1715-16 date proposed by Ingamells and Raines for Roy Miles’ painting. The Miles Master did not anticipate Watteau’s mature works (an improbable assertion in the first place) but, instead, registered the impact of the second generation of painters of the fête galante. It seems more appropriate to assign a date of circa 1730-1740 to his activity.

Finally, there is every indication that the Miles Master was not French as has been assumed for most of the works that have been considered here. Rather, they show the hallmarks of provincial European art, and seem to be by a Netherlandish or German artist. It is perhaps not coincidental that most of the paintings emerged in these areas. As the Miles Master was evidently prolific, other paintings from his hand are bound to turn up. Hopefully one of them will be better documented and will allow us to locate the artist geographically, and perhaps even lead us to his exact identity and true name.

NOTES

1. The painting was not discussed in Roy Miles' autobiography, Priceless (London: 2003). It was subsequently sold, still attributed to Mercier but without any mention of the signature: London, Phillips, Feb. 22, 1982, lot 128.

2. London, Christie’s, March 23, 1973, lot 11.

3. John Ingamells and Robert Raines, “A Catalogue of the Paintings, Drawings and Etchings of Philip Mercier,” Walpole Society Journal, 46 (1976-78), 57-58, cat. 244.

4. For Ingamells and Raines’ change of thought, see Martin Eidelberg, “Philippe Mercier, Watteau’s English Follower,” October 24, 2013, http://watteauandhiscircle.org/Mercier.

5. New York, Sotheby Parke Bernet, March 16, 1979, lot 152.

6. Inv. 880.1.50; donated by Louise Ronot in 1880.

7. Sale, Brussels, Nackers, July 17, 1960, lot 785; Brussels, Nackers, Dec. 18-21, 1968, lot 850.

8. Sale, Cologne, Kunsthaus am Museum, Oct. 18, 1978, lot 1446.

9. At that time it was owned by the Raydon Gallery.

10. The painting was illustrated in Die Weltkunst 23 (December 1979), 1828.

11. Sale, Versailles, June 3-6, 1964, lot 37.

12. Sale, Vienna, Dorotheum, Dec. 2-4, 1947, lot. 46; sale, Vienna, Dorotheum, May 24-26, 1955, lot. 528.

13. Sale, Brussels, Torley, Dec. 20, 1927, lot 7028.