The Nantes Master

© Martin Eidelberg

Created November 2014; revised October 2017

It is often said that Watteau’s fêtes galantes had little impact on eighteenth-century painting as a whole, that their popularity was short lived, and there were supposedly only a few French followers who continued this genre: Jean-Baptiste Pater, Nicolas Lancret, Pierre Antoine Quillard, Bonaventure de Bar, the Octaviens, and François Jerome Chantereau. However, such generalizations overlooks many minor artists who have yet to be recognized. These are often nameless painters whose identities have been hidden under classifications such as “school of Watteau,” “assistant of Pater,” and “follower of Lancret.” Although we still may not be able to supply their proper names, much less any facts about their lives, still, these artists are worthy of study, not only in their own right but also for what they reveal about the development of French painting in the first half of the eighteenth century.

|

|

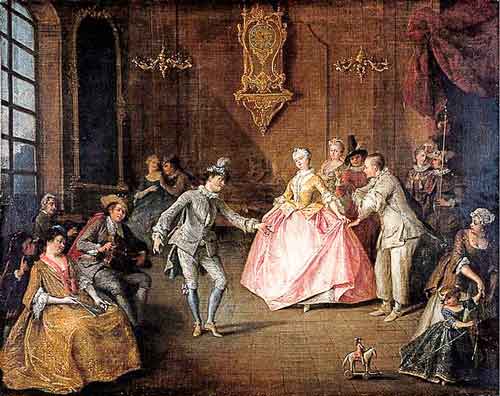

| 1. The Nantes Master, Un Bal, oil on canvas, 65.2 x 81 cm. Nantes, Musée des Beaux-Arts. | 2. The Nantes Master, L’Arrivé à une auberge, oil on canvas, 65.2 x 81 cm. Nantes, Musée des Beaux-Arts. |

The anonymous artist whom I wish to present on this occasion, one of the many “Notname” painters in the circle of Watteau and his satellites, has not been recognized as an individual personality until now. I have named him after two of his works that are in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Nantes (figs. 1, 2).1 They are marked by an elegance of style: attenuated figures with sweeping lines to their costumes and gestures, diminutive heads, and agreeable, smiling faces. They typify what for many is the French rococo aesthetic. These pendants reflect the art of Watteau only indirectly, for they share more with the next generation of Lancret and Pater. Their emphasis on quotidian life among the rich nobility is distinctive. In one, two women have arrived in a chariot pulled by an assortment of dogs—imagery of a sort that Watteau, ever the idealist, never considered. In the other painting, a man and woman dance, although they are apparently about to be interrupted by a man costumed as Gilles. The title of Avant le bal costumé that has been applied to this work seems inapropos, especially since the dance has already begun. It might be more appropriately described as The Dance, The Minuet, or Indoor Entertainments.

These pendants enjoy much in common with the art of Nicolas Lancret. Indeed, they were sold under Lancret’s name in the 1783 sale of the collection of M. de Thesson, maréchal des logis de Madame: “Deux sujets très agréables, l’une représente un Bal & l’autre une Compagnie qui arrive à la porte d’une Auberge. Ces deux Tableaux sont peintes par Lancret.”2 Understandably, then, since their entrance into the museum’s collection in 1810 they have always been associated with Lancret’s name by that institution. Indeed, throughout the nineteenth century they were classified as paintings wholly by Lancret. In a momentary aberration in 1900, Louis Gonse declared that they were “indiscutable” works of Watteau, executed around 1712 when Watteau was first in contact with Crozat.3 Fortunately, Gonse’s proposal was never repeated by Watteau scholars.

In the museum’s 1913 edition of the catalogue, Marcel Nicolle returned to the more orthodox position that the two pendants should be associated with Lancret, but his use of the phrase “attribué à” tells us that he was not fully convinced they were actually by Lancret.4 He clarified his position a few years later, claiming in 1919 that Lancret had conceived but not executed them.5 Two years later he clarified his position with greater specificity, saying that although he had previously classified the pendants under Lancret’s name as a matter of convenience, the execution was somewhat soft and had none of Lancret’s characteristics.6

The generally held opinion in the twentieth century was that although they were not by Lancret himself, nonetheless, they could safely be listed as “attributed to Lancret” (for example, a showing in Paris in 1928), or they could be listed as “manner of Lancret” (the museum’s 1953 catalogue).7 Scholarly opinion has come full cycle and the museum’s most recent catalogue, prepared by Claire Gerin-Pierre, once again has assigned the two paintings to Lancret himself.

|

|

| 3. The Nantes Master, Un Bal. Nantes, Musée des Beaux-Arts. | 4. Nicolas Lancret, Jeu de colin-maillard, oil on canvas, 37 x 47 cm. Stockholm, Nationalmuseum. |

It has been suggested, for example, that one should compare Un Bal with Lancret’s Jeu de colin maillard, now in the Nationalmuseum, Stockholm (fig.4). They have much in common, especially in terms of their explicit narratives and the insistent attention given to the depiction of the rooms’ fittings. The depiction of the fittings in the Nantes painting—the cartel clock, chandelier and other accessories—record a rococo room with great specificity, quite unlike Watteau’s imaginary parks and, in that sense, suggest strong parallels with Lancret’s talents as a painter of domestic genre scenes. But the rendering of the individual figures is not really comparable with Lancret’s manner.

|

-LNG_1sampled.jpg) |

| 5. The Nantes Master, L’Arrivée à une auberge (detail). | 6. Nicolas Lancret, La Tasse du chocolate (detail). London, National Gallery. |

It is significant that almost a century ago, only George Wildenstein openly refused the attribution of the Nantes paintings to Lancret. This was in his 1929 monumental monograph on Lancret. Yet scholars never heeded his sage advice.8 The significant stylistic markers of the Nantes Master’s work such as the proportions of the bodies and the facial features, show nothing of Lancret’s specific manner. The faces are sweet, the features are petit, and there is none of the angularity of chins and noses that we inevitably find in Lancret’s work. The Nantes paintings, I would propose, are by a contemporary of Lancret’s, an artist whom, as we will see, was influenced not only by Lancret but also by Pater.

|

|

| 7. The Nantes Master, Le Bain, oil on canvas, 42 x 57 cm. Whereabouts unknown. | 7a. The Nantes Master, Le Bain (detail). |

Proof of the Nantes Master’s independent identity is found in several additional paintings that can be associated with his oeuvre. A picture of key importance is one that was in several Parisian collections and auctions, then was with the Galerie Pardo in 1980, and appeared last on the market in 2010.9 This scene depicts a woman bathing in a fashionable salle de bain. Attendant females busy about her, arranging her draps de bain, but the servant at the far right mischievously pulls back the curtain to reveal her mistress to the young man outside the door. That he will be smitten with love for her is suggested by the statue of Cupid above the bath, his bow about to send out an arrow to enflame the man’s heart. Adding to the naughtiness of this erotic scene, his square white collar establishes that he is an abbé. The exaggerated portions of these figures, the diminutive doll heads, the fluid movement of their actions—all these factors help identify this painting as a work of the Nantes Master.

|

| 8. Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Bath, 43.2 x 34.3 cm. Detroit, The Detroit Institute of Arts. |

Whereas the Nantes paintings were identified with Lancret, this picture has been associated with Pater and was attributed to him throughout the twentieth century. While the style of the painting is not that of Pater, the theme and overall composition depend upon a Pater genre scene that is known though several variants such as those in the Detroit Institute of Art, the Wallace Collection, and one formerly in the collection of the duc d’Arenberg in Brussels (fig. 8).10 In all these pictures the bathing woman is displayed on the edge of the tub, her attendants hold the draps de bain behind her, in some a servant kneels or sits on the ground before her, and in many a servant pulls aside a curtain to enable the peeping Tom. The details vary from one version to another—some have vertical formats, others horizontal; the servant on the ground is seen either from behind or in profile, sitting or kneeling, and only some show the man peering through the glazed doorway. None of the variants have all the details that must have been present in the model that the Nantes Master used for his imitation, but it is evident that such a prototype did exist.

|

| 9. The Nantes Master, La Partie de musique, oil on canvas, 41 x 57 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

A fourth work to be added to the oeuvre of the Nantes Master is La Partie de musique, a painting almost identical in size to Le Bain. It had previously been attributed to François Octavien but the analogies with Octavien’s work are too general to be considered seriously.11 Here, a woman at a clavier, a man on cello, a youth on a violin, and a singing cleric perform to the delight of those assembled. As in Un Bal, the artist has emphasized the details of the furniture (note the extraordinary compound curves of the clavier’s leg) and the wall decoration. A constant note in the Nantes Master’s work is that the figures are constrained to a frieze across the lower two-thirds of the composition, leaving a relatively empty upper portion that creates a contrasting sense of open space. Not least, this painter has a penchant for adding elements into the lower two corners to balance the compositions. In La Partie de musique, the woman at the left and the small child and a still life of additional instruments at the right fulfill this function. In Le Bain, a seated woman at the left and a chair turned at an opposite angle brace the composition. In the Nantes paintings, people are posed in the opposite corners. This distinct formula serves as another hallmark of the painter.

|

| 10. The Nantes Master, Le Jeu de colin maillard (Pierrot abusé), oil on canvas, 92 x 114 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

A fifth and final work to be added to this painter’s oeuvre is a scene of blind man’s bluff that appeared at auction in Paris in 1982, attributed simply to a French early eighteenth-century artist (fig. 10).12 The lady at the center of the composition is a “sister” of the woman arriving in a dog chariot and the women at the far left and right of the bath scene. Her facial features, elongated proportions, and fluency of movement establish the common bond between these paintings. Once again, the theme of the painting, a game played by adults, while appearing once in an early composition by Watteau, was far more popular among the artist’s followers, Pater and especially Lancret. Our nameless master was indeed an artist of his time.

Who was the Nantes Master? The association of some of his works with both Lancret and Pater, but not with Watteau, suggest that our Notname was active after 1725, more probably after 1730. There is insufficient grounds to place him directly in Lancret’s or Pater’s atelier, even if his style and choice of subject matter show that he was abreast of their work. Indeed, he seems to have been au courant of Parisian developments in general. But it would be foolhardy to postulate any further conclusions about his career, not, at least, until more concrete evidence is found.

The Nantes Master did not have notable talents and yet he was not unskilled. His works possess charm and grace, and offer visual pleasure. While it is unlikely that his identity will be uncovered soon, still, there is the hope that some day his name will emerge.

NOTES

1. For a full account of the paintings’ history and bibliography see Claire Gerin-Pierre, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes, catalogue des peintres françaises, XVIe – XVIIIe siècle (Paris and Nantes: 2005), 146-47, cat. 154-55.

2. Sale, Paris, Nov. 24ff, 1783, lot 69. They were measured at 2 pieds by 2 pieds, 6 pouces (i.e., 61 x 76.2 cm), which is slightly smaller than their actual dimensions. However, as often in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, they may have been measured while in their frames.

4. Marcel Nicolle and Émile Dacier, Musée municipal des Beaux-Arts, Catalogue (Nantes: 1913), cat. 636.

6. Idem, “Watteau dans les musées de province,” Revue de l’art ancien et moderne, 40 (July-Aug. 1921), 134.

7. La Vie parisienne, exh. cat. (Paris: Musée Carnavalet, 1928), cat. 68; Luc Benoist, Nantes, Musée des Beaux-Arts, catalogue et guide (Nantes: 1953), cat. 635-36.

9. Chateau de Villersexel, collection of the marquis de Gramont; sold Paris, Hôtel Drouot, May 25-26, 1932, lot 86; M. J. Lantz; Paris, Galerie Pardo, Catalogue, 1980, IX; sale, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, Dec. 13, 2010, lot 32.

10. See Héritage de France, French Painting 1610-1760, exh. cat. (Montreal: Museum of Fine Arts et al.: 1961), cat. 57. See also Florence Ingersoll-Smouse, Pater (Paris: 1928), cat. 307-10.